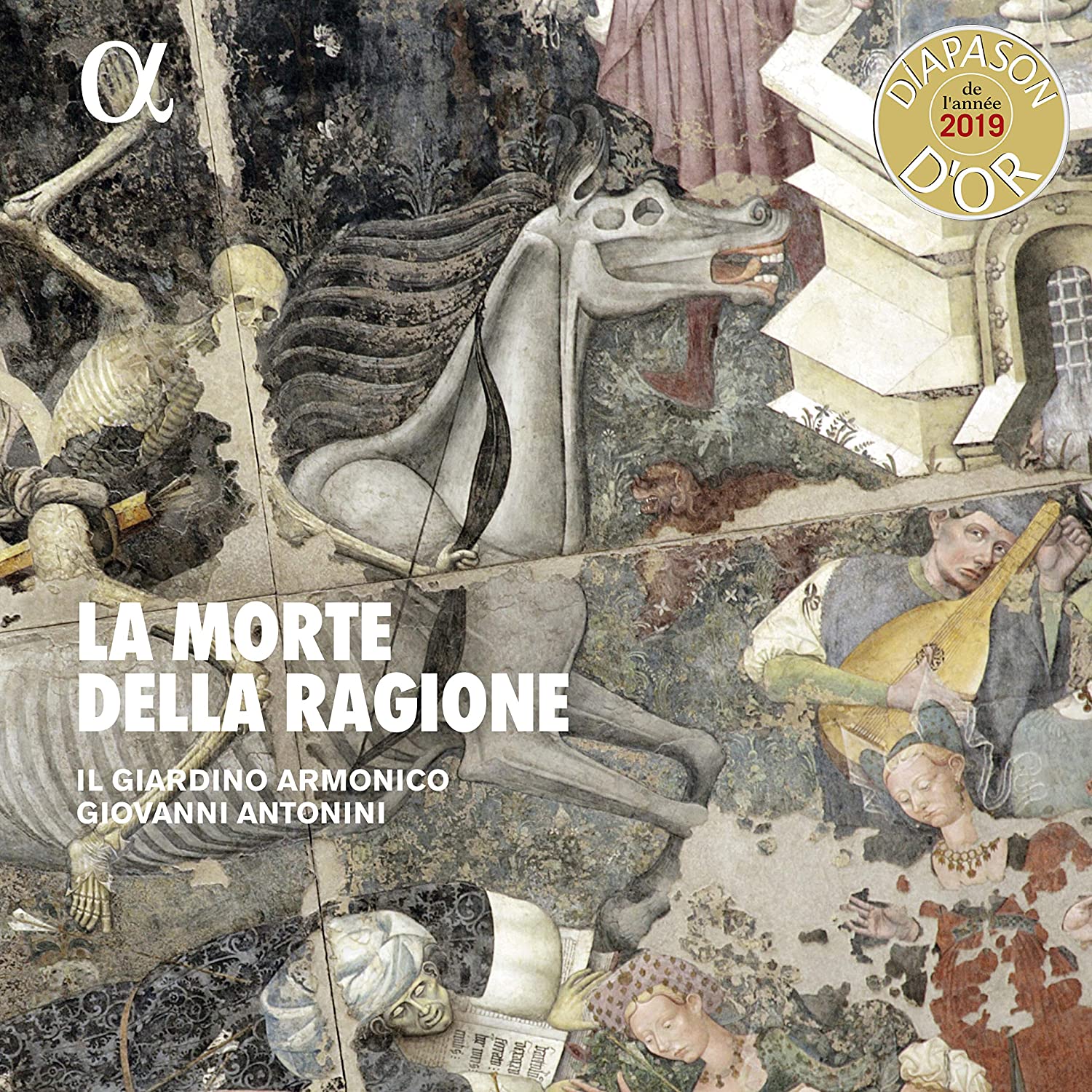

Il giardino armonico, Giovanni Antonini

73:07 (CD in a hard-backed book)

Alpha Classics ALPHA450

Click HERE to buy this CD on amazon.co.uk

Under the title the death of reason, Giovanni Antonini has brought together a rather random collection of pieces from the 15th to the 18th centuries. If you don’t worry too much about finding a linking theme, you can just sit back and enjoy the accompanying lavishly illustrated colour book while wondering at the stunning virtuosity of Antonini (recorders) and his ensemble. In fact, the contents of the book amount to a rather slight essay translated into various languages, followed by a series of chunks of related source material on the music and aspects of performance in an extended appendix. So spontaneity, even anarchy, is the flavour of the moment, but there is some lovely music imaginatively performed here. We have works by Christopher Tye, Hayne van Gizeghem, Josquin, Agricola, Dunstable, Gabrieli, Gombert, Viadana, Gesualdo, Scheidt, and van Eyck to name but a few, performed instrumentally, imaginatively and never less than very musically by the ensemble – perhaps best to read the appendix section on ‘tremoli and vibrati’ to help with understanding Antonini’s idiosyncratic recorder playing. One of the chief joys of this set remains the wealth of colour illustrations from a range of Renaissance paintings and books to enjoy as an accompaniment and enrichment to the music. To sample the virtues and some of the randomness of this CD, listen to the group’s highly individual interpretation of the familiar Susato Battle Pavan (track 13).

D. James Ross