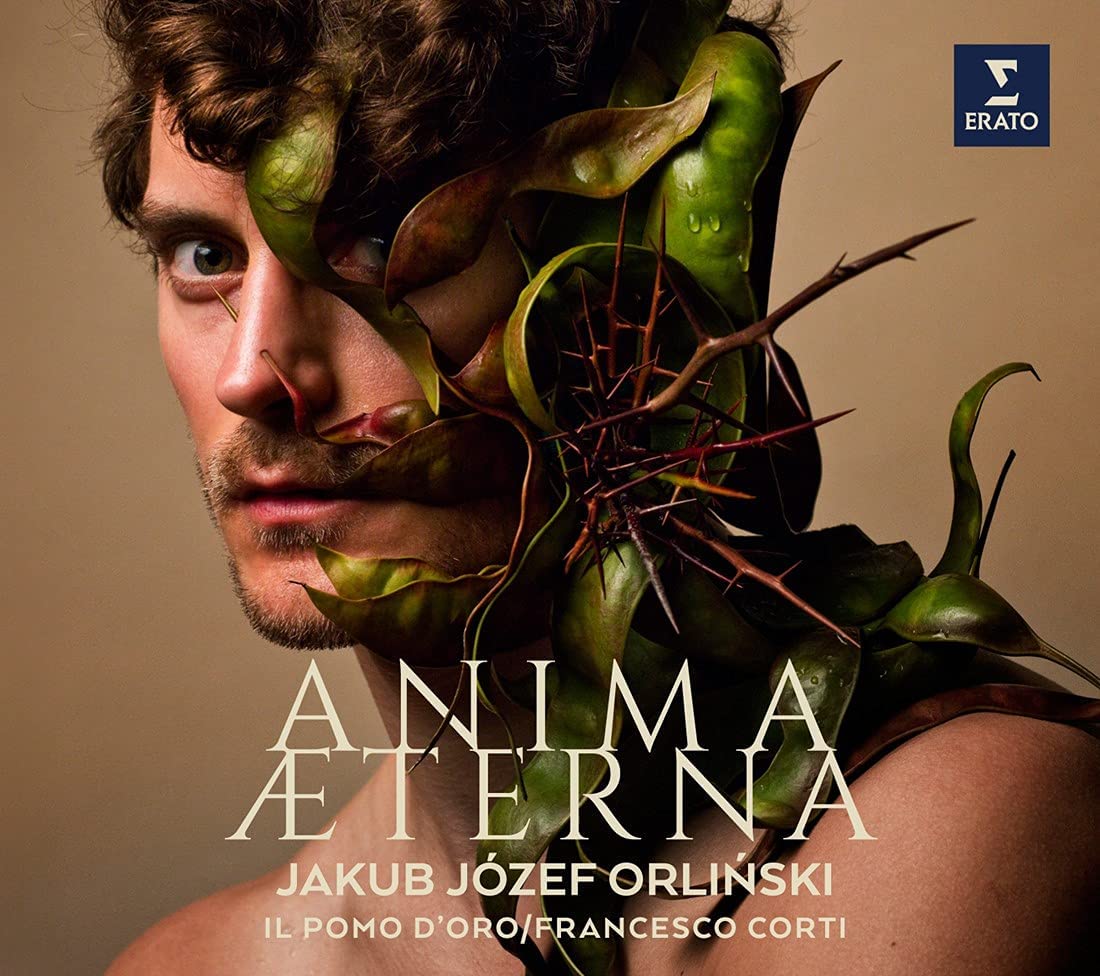

Jakub Józef Orliński countertenor Fatma Said soprano, Chorus and Orchestra of Il Pomo D’Oro, directed by Francesco Corti

80:21

Erato 0190296743900

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[Using these sponsored links is the only way you can support this FREE site]

Polish countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński first came to notice in a YouTube video singing an aria from Vivaldi’s Il Giustino. Endowed with a ravishing voice of a pure golden sweetness, the looks of a young Hollywood star and an exceptional if not perfect vocal technique, Orliński’s video rapidly achieved cult status and a recent check showed it has received over 8 million viewings. A follow-up video of him break dancing did no harm either. Since then, however, he has shown himself to be more than an ephemeral boy wonder, producing fine CDs of both sacred and secular arias in addition to singing Ottone in what has to be referred to as Joyce DiDonato’s Agrippina.

Here Orliński returns to sacred repertoire in a programme that includes several rarities, though I suppose it is a sign of the times that the singer is quick to point out in his introductory note that it is not the religious side that is the principal focus. In a sense, there is some justification for that in that all this is music of the counter-Reformation, music that owes much to opera and is designed to appeal more to the senses than it does to the soul. Nothing better illustrates this than the opening motet by Zelenka, Barbara, dira, effera, Z 164, a furious outburst against the crucifiers of Jesus – the text reads uncomfortably today – driven by fierce, taut rhythms and melodic angularity typical of the composer. Consisting of a long, unusually structured opening aria, a short recitative and the final ‘Alleluja’ customary in motets, it’s a bravura piece well suited to displaying Orliński’s vituoso gifts, in particular the dazzlingly articulated passaggi. Less admirable is a reluctance to introduce trills, which as I’ve previously noted he can sing but appear still to be work in progress rather than a confident part of his technique.

The other side of the Orliński coin is strikingly in evidence on the following track, an aria for the Repentant Sinner from Fux’s sepolcro – oratorios staged at the imperial court in Vienna in Holy Week – Il Fonte della salute (1716). A beautiful continuo aria with an obbligato part for baryton, it provides the ideal vehicle for the singer to display the sheer beauty of his voice and unwavering sense of line and shaping. Another motet by Zelenka, a setting of the Vespers psalm Laetatus sum, ZWV 90 is a duet for which Orliński is joined by the bright, flexible soprano of Fatma Said. The opening duet has an entrancing, dancing lightness exceedingly well captured here, while succeeding movements including solo arias for both voices as well as further brief duets, in which the voices combine exquisitely, especially in the setting of ‘Gloria’, which underlining the point made above could in a different context well be a love duet. With the exception of the brief Handel antiphon with which the programme ends, the remaining items are by less familiar composers. ‘Giusto Dio’ by the Portuguese composer De Almeida (1702-1755) and is prayerful plea of great beauty from his oratorio La Giuditta, again allowing Orliński to demonstrate his legato and including a central section that calls for his impressively strong chest register. The da capo opens with a lovely messa da voce and although the aria is taken at an indulgently slow tempo, the overall effect is so beguilingly luxuriant I for one am not complaining. Even less well known is Bartholomeo Nucci (fl. 1717-c.1749), from whose oratorio Il David trionfante comes a rather conventional trumpet aria, the martial tones and virtuoso character of which tempt Orliński into a rather vulgar cadenza. Of greater substance is the setting of Laudate pueri by Gennaro Manno (1715-1779), a member of a family of musicians and for a period joint maestro di cappella at Naples Cathedral with the aging Porpora. Following a florid opening nicely contrasted sections also include choral interjections, the only work on the CD to do so.

Overall, the programme vividly enhances Orliński’s now-established credentials as a serious singer rather than a celebrity. Given the unfamiliarity of much of the programme, it is a pity that the notes are so unhelpful; Manna is omitted completely. I’m not sure what to make of a cover picture that seemingly finds Orliński in mid-Ovidian metamorphosis into some kind of greenery.

Brian Robins