Il Giardino Armonico, Giovanni Antonini

Symphonies 28, 43, 63 + Anonymous (Sonata jucunda), Bartók (Romanian folk dances)

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Not the least of the pleasures of this exhilarating series has been the works supplementing the Haydn symphonies, invariably to some (at times tenuous) thematic purpose. This time we are given perhaps the most surprising to date, the set of Bartók’s seven tiny Romanian folk dances originally for piano, but orchestrated by the composer in 1917. So if you’ve ever wondered what Bartók sounds like on period instruments, now’s your chance. The results are nothing less than electrifying, given the virtuosity and verve of Antonini’s superlative players, whether in the scrunchy chords of no. 1, the rubato brought to no. 2, the wistful no. 4, with its plangent violin solo, or the extraordinary sound of Giovanni Antonini’s Renaissance flute in no. 3. All is explained in his notes, devoted to what Antonini describes as ‘the birth of crossover’, or music from traditions other than so-called ‘classical music’.

Also falling into this category is the anonymous Sonata Jucunda (‘cheerful sonata’), a manuscript from the important collection housed in Kromĕříž Castle in Moravia, which also includes the manuscripts of a number of Haydn’s works. Composed in the style of Biber, it includes eleven brief connected movements that evolve from a solemn opening adagio to incorporate traditional music from the Haná region of Moravia, some sections given a delightfully quirky character.

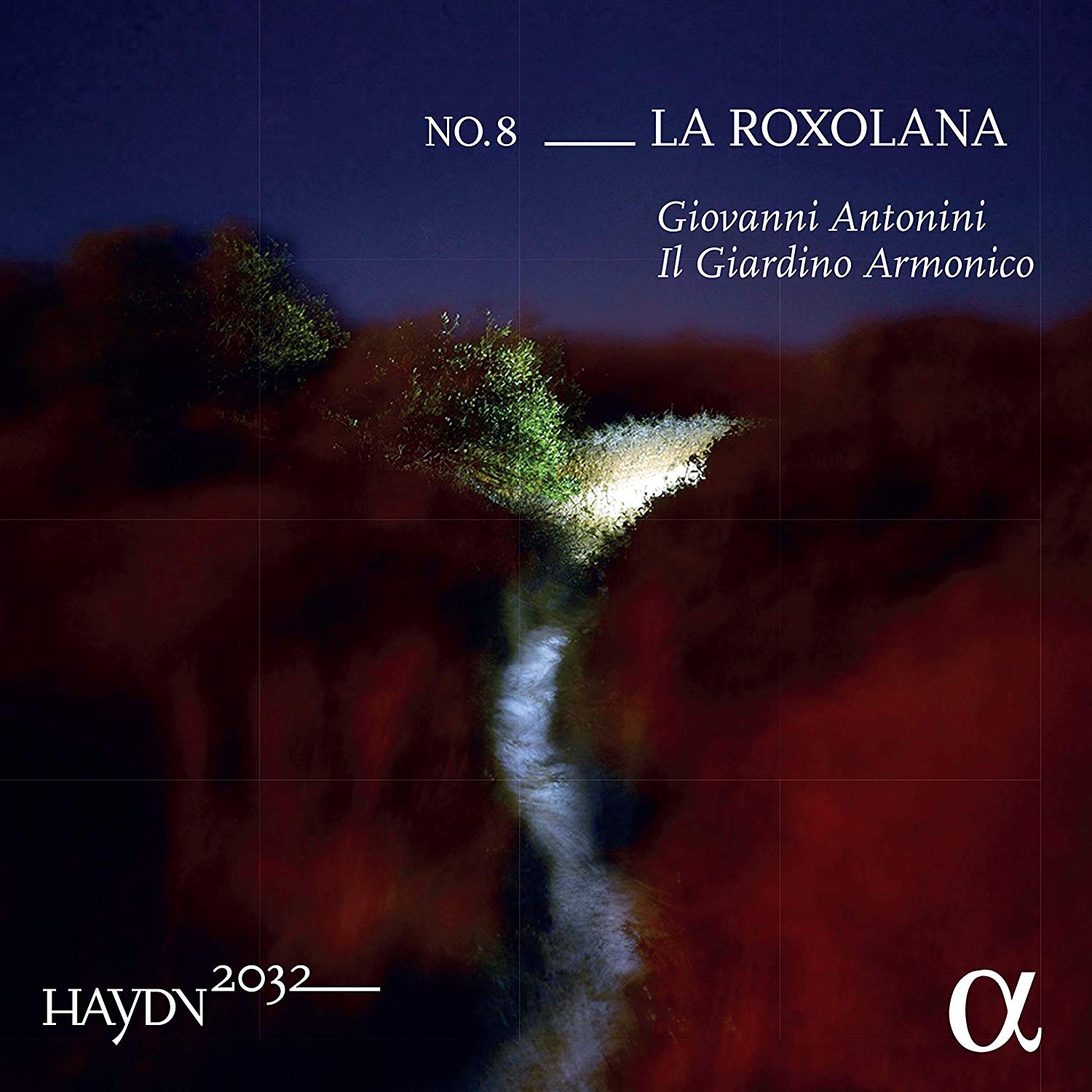

The earliest of the three Haydn symphonies is No. 28 in A, a modestly scored work that dates from 1765. H. C. Robbins Landon conjectured that it originated as incidental music for a play presented at Eisenstadt in that year, an idea expanded by the notes for the present CD, which suggests the comedy Die Insel der gesunden Vernunft (The Isle of Common Sense) as the source. The opening Allegro certainly has a feel of barely suppressed excitement before eventually breaking out in the full orchestra, while the Poco Adagio suggests a nocturnal walk. Robbins Landon believes it could have served as an entr’acte. Symphony No. 43 in E-flat, nicknamed ‘The Mercury’ in the 19th century for no discernable reason, dates from 1770. It opens with a strongly announced chord, answered by sotto voce strings before proceeding to an animated Allegro bristling with tremolandi. The Adagio is wonderfully atmospheric, a lyrical musing that in its second half moves to a world of introspection. If No. 28 can conjecturally be linked to a stage work, no such doubts arise with Symphony No. 63 in C, the work that gives this volume its name. Composed around 1779/80, it is one of several composite symphonies from that period. The affable opening Allegro is taken from the overture to the comic opera Il mondo della luna, composed in 1777, while the nocturnal theme of the succeeding set of variations, ‘La Roxelana’ comes from incidental music for a play given at Ezsterháza in which the French lady of the title wins the favour of the Turkish emperor Suliman in the face of competition from two other ladies. The bustling Presto finale again has the feel of theatre.

All this music is played with dynamic panache, along with the sensitivity and delicacy all noted as characteristics of earlier issues. With well-judged tempos and acute balance enabling part-writing to be revealed in translucent textures, these are performance that convey a spirit of fresh spontaneity, while at the same time giving full value to every single bar.

Brian Robins