The Brabant Ensemble

70:39

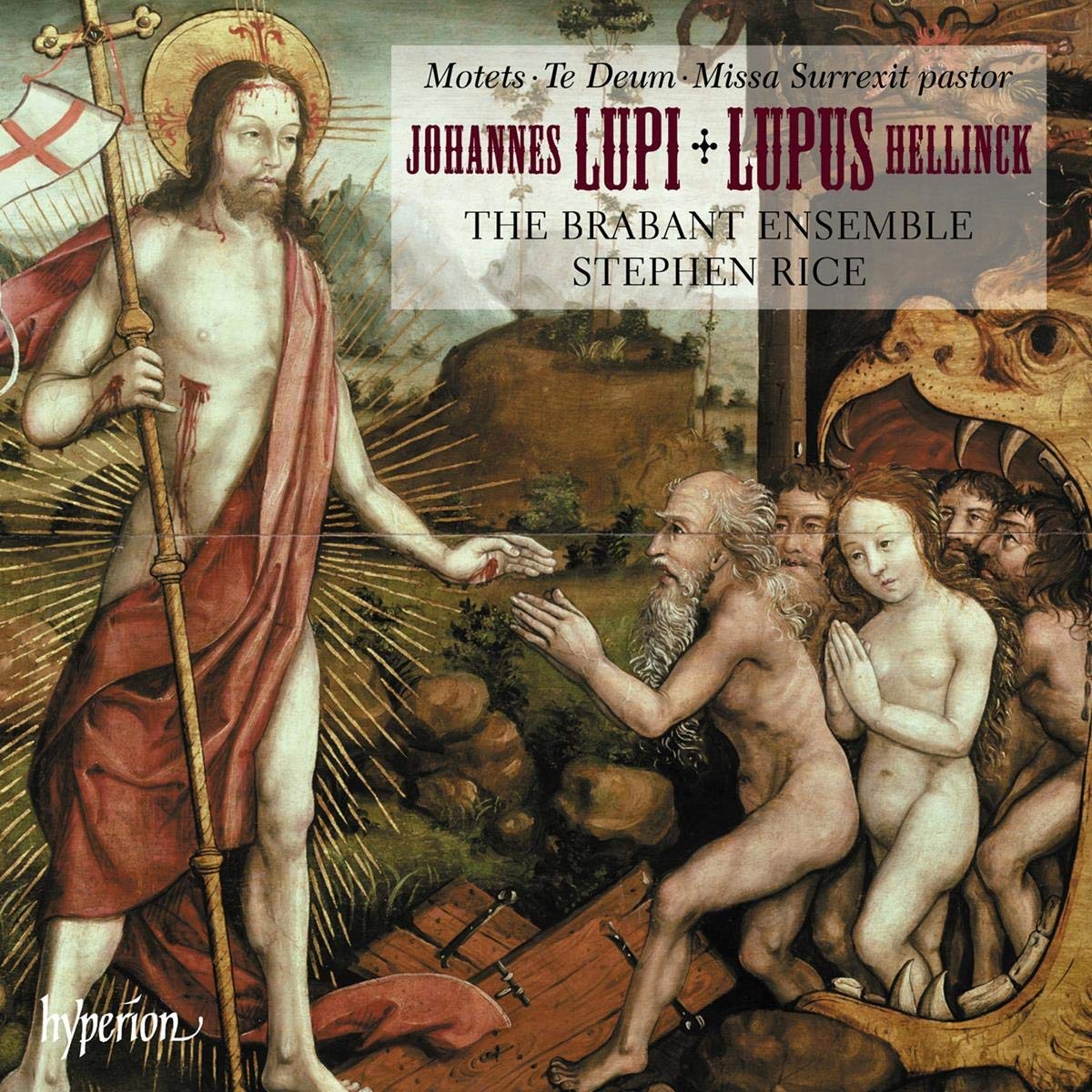

hyperion CDA68304

Recording and releasing a programme of music by two composers whose names are unknown (and almost comically similar) could be seen as a risk. Needless to say, Stephen Rice can be trusted to spot talent even when it has lain dormant for five centuries. Lupus Hellinck (1493/4-1541), seemingly a Dutch speaker, spent his career in the Low Countries at Bruges, now the capital of West-Vlaanderen, or West Flanders, in modern Belgium. His mass, based upon a motet by Andreas De Silva (c. 1475/80-c. 1530), begins with a pleasant and competent Kyrie, whereafter, while following the musical narrative, the ear picks up judiciously placed musical gems in each movement, including a delicious dissonance closing the first section of the Gloria, a beautiful cadence closing the first section of the Credo, then best of all a glowing Hosanna to the Sanctus. This is sung more animatedly when repeated after the Benedictus, rising to sheer incandescence. The Benedictus itself is an austere duet for tenor and bass (not present in the print of 1547 used for the recording, but preserved in a manuscript source) making the impact of the concluding Hosanna all the more thrilling. A fine Agnus leading to a quite sublime “Dona nobis pacem” brings this rich and rewarding work to a close.

Johannes Lupi (c. 1506-1539) spent most of his career at Cambrai, then also in the Low Countries but subsequently annexed by France. The three motets and Te Deum here emanate from a voice quite different from Hellinck. Salve celeberrima virgo is a thrilling piece in eight parts, evocative but not derivative of Gombert, laced with piquant dissonances and some sweeping themes. Quam pulchra es sets some particularly arousing verses from The Song of Solomon. The ostensibly incongruous but extravagantly florid Amen after the concluding text “Ibi dabo tibi ubera mea” – There will I give you my breasts – could be heard as a response to those words, albeit they are also laced with some more piquant dissonances by Lupi. It all leads one to raise an eyebrow at the idea of this particular Biblical Book being other than a masterpiece of very secular erotic poetry. Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel, notwithstanding the presence of a setting of the Te Deum as the following and concluding track, is, as Stephen Rice observes in his scholarly booklet, “a free-standing motet” and not a canticle. The Te Deum itself is through-composed but although Lupi sets it sectionally, Stephen Rice bustles it along without losing any of the appetizing details, such as (yet more) dissonances towards the end of tracks 25 “Tibi omnes angeli” and 28 “Te per orbem”, and the interesting cadences closing tracks 27, 30 and 34, “Te gloriosus apostolorum chorus”, “Tu ad liberandum” and “Salvum fac” . He also strategically relaxes the tempo during track 28. Lupi himself provides variety with some homophony throughout most of track 32 “Te ergo quaesumus” amongst the prevailing polyphony; and with some reduced scoring occasionally down to two voices in passages dotted throughout the canticle. Stephen Rice notes that in track 36 the section “et laudamus nomen tuum” is in fauxbourdon. It provides a crashing change of gear from the rest of the work, as if a mediaeval voice has risen to intervene in this mellifluous Renaissance composition. Yet, perhaps because fauxbourdon is part of the creative continuum from which Franco-Flemish polyphony evolved, Lupi integrates it superbly, adding it to the ingredients which go towards making this piece a worthy conclusion to a disc which brings these two composers back into the limelight where, on the evidence of this recording, they both so deservedly belong.

Richard Turbet

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk