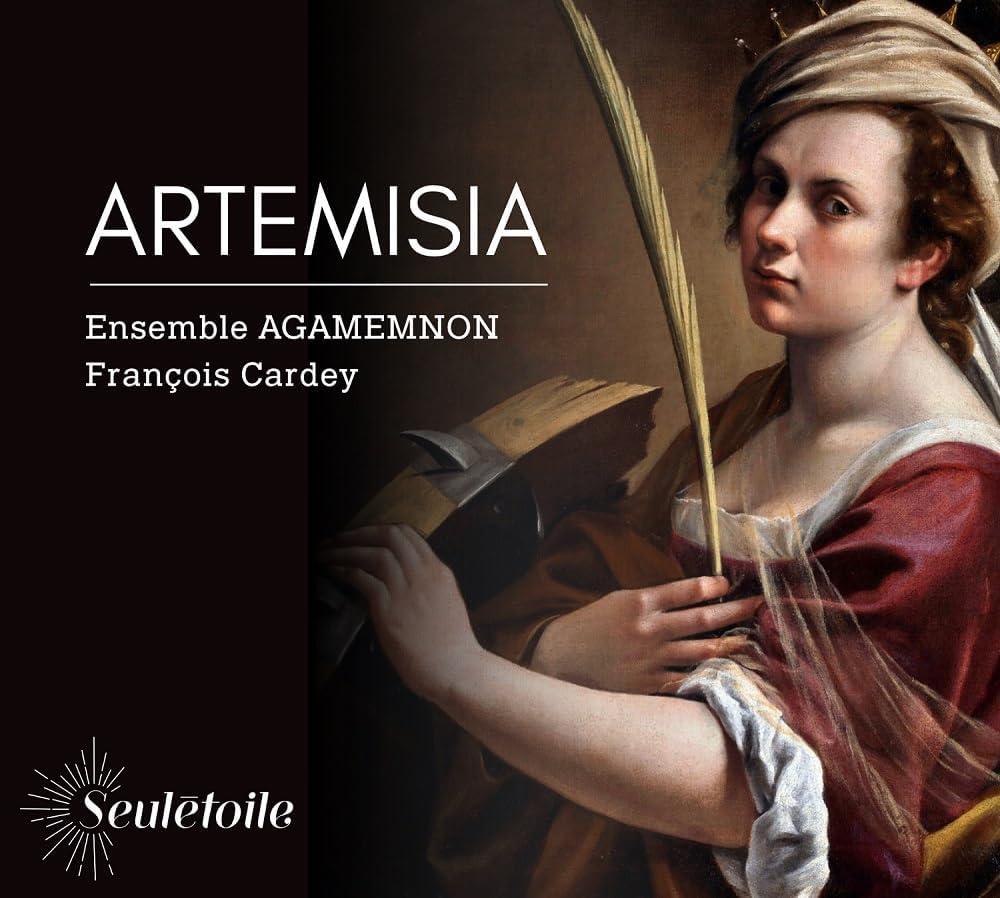

Hager Hanana

53:07

Seulétoile SE 06

Music by Weiss, Abel, Bach, Biber

A fine account of the sixth of Bach’s Suites for solo cello BWV 1012 on the violoncello piccolo is at the heart of this programme of music for this diminutive cello. When they first appeared, cellos existed in various sizes, and a couple such as the piccolo survived into the Baroque period, and Hager Hanana’s choice of repertoire hints at what they might have been playing. While this Bach Suite out of all the six he wrote seems to lie best for cello piccolo and was probably composed with the instrument in mind, Hanana fills out her programme with two pieces for viola da gamba by Carl Abel and music originally composed for lute by Leopold Weiss. She concludes her programme with a fine account of the Passagaglia, ‘The guardian angel’ from Biber’s Rosary Sonatas, originally for solo violin. It has to be said that all of this music works very well on Hanana’s chosen instrument, and, in the general absence of solo repertoire specifically for cello piccolo, these pieces seem like a valid option. Hanana plays her anonymous 18th-century cello piccolo with commitment, skill and musicality, and these performances are convincing and enjoyable.

D. James Ross