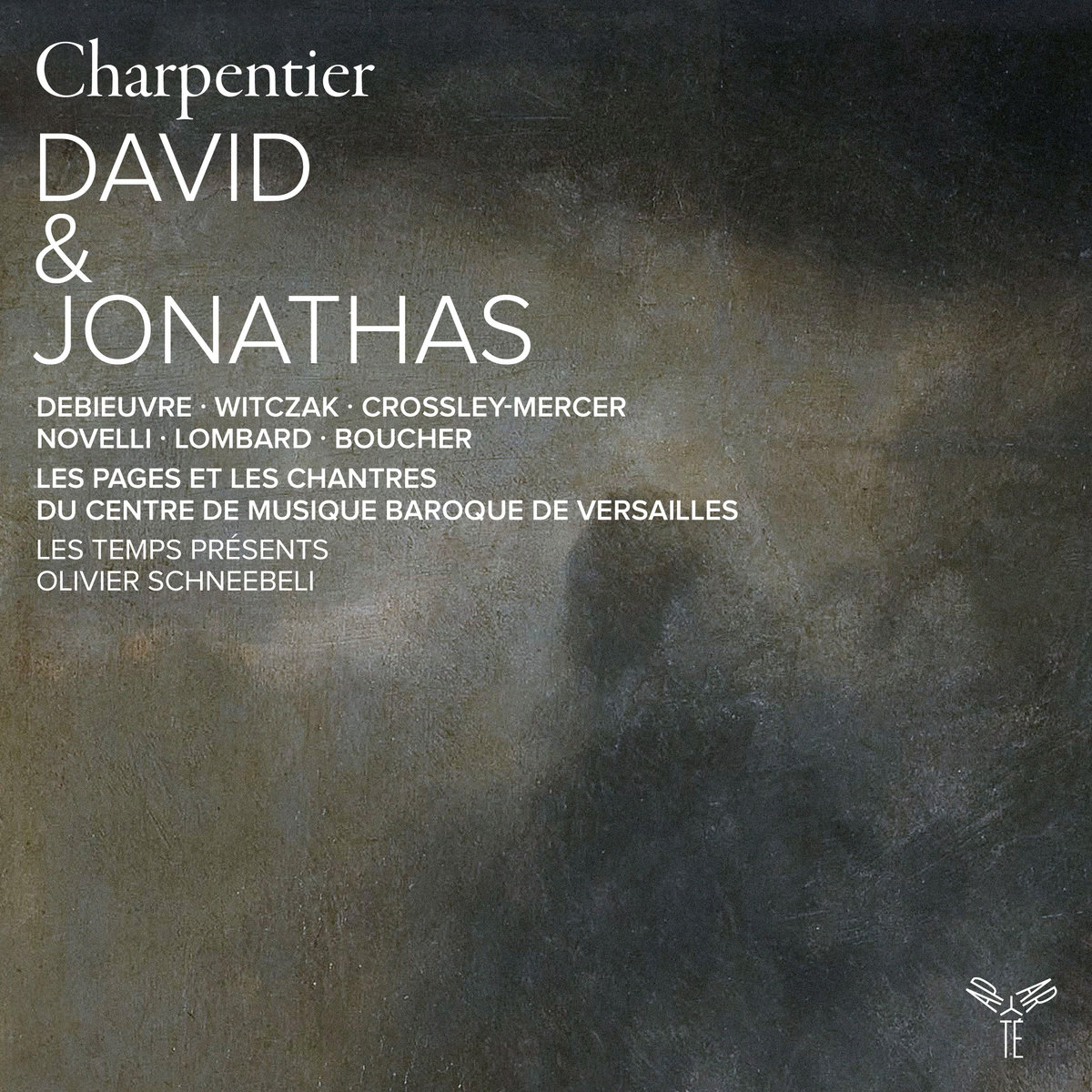

Clément Debieuvre David, David Witczak Saul, Edwin Crossley-Mercer the ghost of Samuel/Achis, Jean-François Novelli Joabel, Jean-François Lombard Pythonisse, Natacha Boucher Jonathas, LesPages et les Chantres du Centre de musique baroque de Versailles, Orchestre Les Temps Présents, directed by Olivier Schneebeli

122′ (2 CDs in a CD-sized book)

aparté AP342

David et Jonathas owes its existence to the tradition of the Jesuits of the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris staging plays and musical dramas during the course of carnival season. It dates from 1688, when it was staged between the acts of a now-lost spoken drama. It should be recognised that it is an opera, not an oratorio and as such has a framework familiar for the tragédie en musique, that’s to say a prologue and five acts. Only the relative brevity of the work, with less importance attached to the divertissements and fewer dances than usual mark it out as unusual in that respect.

As was widely recognised from its first performances David et Jonathas is a powerful masterpiece. It is indeed one of the great pieces of late 17th-century French theatre, apparent from the outset of the prologue, which to the best of my knowledge is unique in being a part of the action. In concerning itself not with the usual royal panegyrics but rather with the visit of Saul to the Witch of Endor (Pythonisse) and the fateful utterances of the ghost of Samuel, it provides an introduction to the drama that will unfold, drama culminating in the final tragedy of the deaths in battle of Saul and his son Jonathan. Yet because the opera has a didactic purpose its ending is not tragic, but rather a brilliant paean of praise to the victorious David, the man who remained obedient to God’s laws, in contrast to the defeated Saul, who has not. More importantly still, the opera is an investigation of human relations on a psychological level rare in opera of this period, specifically the complex love between Saul and David, and those of the brotherly love between David and Jonathan. At their heart are the great monologues given to all three, their lyricism again a distinguishing feature of an opera in which récitatif plays a smaller than usual role.

In 2022 the opera was given a superlative production and performance in the Chapelle Royale at Versailles, a highly appropriate venue given its original commissioning by the Jesuit fathers of the Collège Louis-le-Grand. That performance has already been issued on CD and DVD on Versailles Spectacles. The set to hand was made live at Versailles, but was a concert performance given in the Opéra Royal the previous year. Ironically it is this performance that seeks to come closer to the original 1688 performance than the staged production in the Chapelle by using a children’s choir for the upper voices and a child for the role of Jonathas, though in this instance a girl rather than a boy. The present performance also almost certainly comes closer to the original performance at the Collège by using considerably smaller orchestral forces, although the playing of the somewhat oddly-named Orchestre Les Temps Présents (it is a period instrument band) is excellent. Also giving a hint of the context of the Jesuit performance is the inclusion of brief spoken 17th-century ‘déclamations’ placed as introductions to each act and, especially movingly, immediately after the death of Jonathan. Thus rather than a play serving as the context, the spoken word provides interludes to a music drama.

One of the features of David et Jonathas is that in contradiction to the title, the leading character is neither Saul’s son nor his much loved David, but the king himself, his tortured soul revealed in a manner and to a depth rare in Baroque opera. The role is here taken by bass David Witczak, heralding the overwhelmingly searing and insightful characterization he brought to the role just over a year later in the Versailles production. David is sung by contre-ténor Clément Debieuvre, an alumnus of the CDMBV. His voice is lighter and more youthful in timbre than that of Reinoud Van Mechelen, whose assumption of the role was one of the glories of the production. Since the biblical David was young, some may feel Debieuvre’s sensitive if less authoritative performance is more authentic, but there’s no gainsaying Van Mechlelen’s authority. There is of course no valid comparison between the respective interpreters of Jonathas, but the sweet-voiced Natacha Boucher achieves an immensely touching degree of sensitivity in the events leading up to his death (act 5).

The remaining smaller roles are all well filled, with the experienced Edwin Crossley-Mercer a resonant Ghost of Samuel (in the prologue) and Achis, Saul’s general.

There is no question that David et Jonathas is one of the masterpieces of Baroque opera. The story is dramatic, Charpentier’s music magnificent. And like all masterpieces, it is capable of responding to alternative approaches. This version – orientated as it is toward its original college production – is in any event very different to the magisterial Versailles recording. Both have a more than valid place in the catalogue, as indeed does the earlier Erato set under the direction of William Christie.

Brian Robins