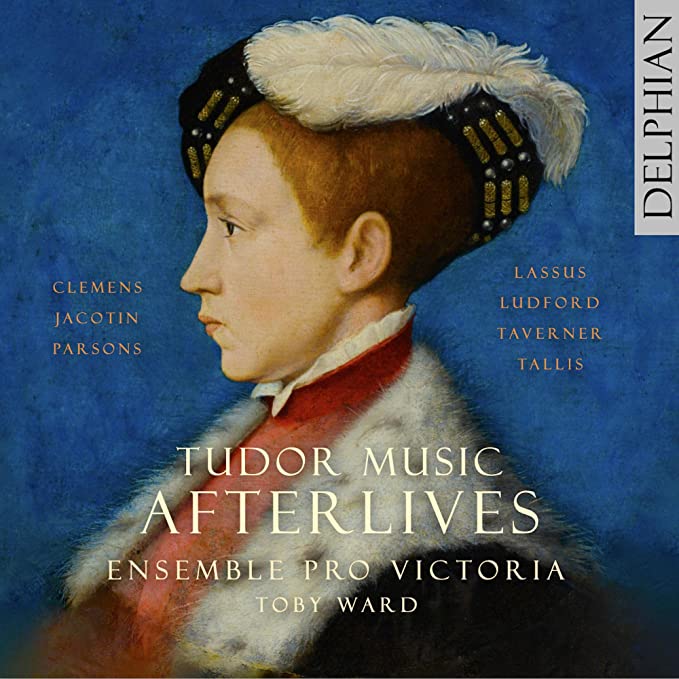

Ensemble Pro Victoria, conducted by Toby Ward, Magnus Williamson, organ. Toby Carr, lute

69:27

Delphian DCD34295

This is Ensemble Pro Victoria’s successor to their rewarding recording of music celebrating the quincentenary of Fayrfax, which I reviewed. And a very successful successor this album is too. The premise on which it is based might seem a tad academic, but it produces a fascinatingly varied yet coherent programme of music, containing some staggeringly fine pieces, excellently performed.

All these pieces are caught in their afterlife, and are presumed or known to have had a prior existence. There are several strands to this programme: “extreme” reconstructions of some of Sheppard’s many fragmentary psalm settings; reconstructions of sections of longer motets that survive only as solo songs with lute accompaniments; a reconstruction of a partsong by Robert Parsons – the stunningly beautiful When I look back – from isolated partbooks and a lute intabulation; Continental motets and chansons that have made their way over to England; excerpts from Ludford’s Lady Masses; two motets with only Elizabethan attributions to Taverner, who died over a dozen years before she ascended the English throne; and a famous work by Tallis – successively a fantasia, O sacrum convivium and finally (among other contrafacta) I call and cry – that seemingly began life as an instrumental work for a consort of viols, with an afterlife serving both the Roman and English Churches.

Musically the most interesting works are the two attributed to Taverner and the motet by Clement. It is unlikely that anyone listening to a “blind tasting” of Quemadmodum would guess that it is by Taverner; indeed, of its five surviving sources, two are anonymous, one ascribes it to Tye, and the other two to Taverner. All these sources are Elizabethan, and none provide any text beyond the initial word. The text of Psalm XLI can be fitted to the notes, so it is reasonable to conclude that it was composed as a motet but was performed instrumentally during its Elizabethan afterlife. What is beyond dispute is that it is one of the most strikingly beautiful works from the Tudor period. In the same class is O splendor gloriae which has Elizabethan ascriptions both to Taverner alone and jointly – respectively the first and second sections – to him and Tye (that man again!). It seems credible that the latter is accurate: either a work on which the two composers agreed to collaborate, or one that Taverner left unfinished and Tye completed; it is even possible that two independent compositions were at some point yoked together, as for instance seems to be the case with the two parts of Byrd’s anthem Arise O Lord/Help us O God albeit they are by the same composer. Clement’s Job tonso capite simply illustrates why he is among the finest composers of his own and of all time.

Musicologically the most interesting works are the five settings by Sheppard of Sternhold and Hopkins’ metrical psalms. These will be published in the forthcoming volume of Sheppard’s complete vernacular music in Early English Church Music, edited by Stefan Scot. Except in one case, only the upper voice of the original four survives for each of these 48 pieces, but the “extreme reconstruction” by Magnus Williamson mentioned above has produced five credible pieces of music for this disc. Given the constraints of a CD booklet it is good that Magnus has been able to summarise the process of reconstruction for each individual psalm. Meanwhile in the Mulliner Book there is an arrangement for keyboard of Sheppard’s setting of Psalm I, The Man is Blest, which, in the words of Stefan Scot, “permits a reconstruction and indicates something of the style of the remaining choral psalms.” Academia Musica Choir, conducted by Aryan O. Arji, recorded all of Sheppard’s Collected Vernacular Works on two discs (Priory PRCD 1081 and 1108, 2013 and 2015) and The Man is Blest is the first track on volume II. Mulliner’s arrangement is played on the organ by Michael Blake (who is scandalously uncredited!) on volume I, track 8.

The two Kyrie movements from different Lady Masses for three voices by Ludford perhaps fall within the category of worthy, albeit pleasantly so, and are enhanced by verses played on the organ by Magnus Williamson employing authentic methods of improvisation on given melodies called “squares”, but the third such movement, Alleluia. Veni electa mea, is, in modern colloquial parlance, an absolute belter, for all its brevity. Like the motet by Clement mentioned above, it illustrates why Ludford takes his seat at the same table as Clement himself, beside Sheppard, Lassus, Taverner, Tye and Tallis, to name only composers present on this disc.

Ensemble Pro Victoria sing all this varied music consistently well, be it plainsong or the augmented forces assembled for O splendor gloriae. I was concerned that the full-throated sound exhibited in some tracks on their disc of Fayrfax might be reproduced here and overwhelm the more understated material. This proves not to be the case. The performances and interpretations, whether assertive, neutral or restrained, are appropriate to each item. Toby Carr’s occasional contributions on the lute with the singers provide both variety of texture and authenticity. The organ played by Magnus Williamson, mentioned above, was built by Goetze and Gwynn in 2002 for the Early English Organ Project, and embodies evidence from fragments of pre-Reformation organs discovered in Suffolk. This combination of cutting-edge scholarship and outstanding performance gives us a recording of the highest quality, apt for edification and pleasure.

Richard Turbet