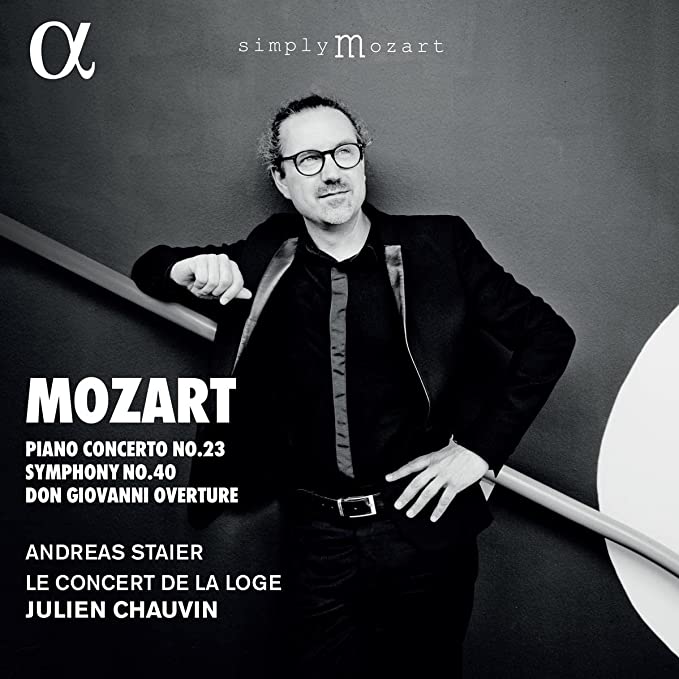

Andreas Staier fortepiano, Le Concert de la Loge, Julien Chauvin violin & director

56:59

Alpha 875

Named in part – they had to drop ‘Olympique’ after protests from the French Olympic association – after the Parisian concert organisation that commissioned a set of symphonies from Haydn, Le Concert de la Loge was founded by the violinist Julien Chauvin in 2015. Today it is firmly established as one of the many outstanding period instrument orchestras in France, having gained a particular reputation (at least on record) in Classical repertoire. For the present CD, they have joined forces with the distinguished forte-pianist Andreas Staier, who plays one of Mozart’s best-loved concertos on a very fine copy of a Walter instrument of c.1790 built by Christoph Kern of Staufen. Those coming across the disc may be surprised to find that the G-minor Symphony has acquired an unlikely nickname – ‘Le Dodécaphonique’. Apparently, it was chosen by the musicians of Le Concert following a contest among their concert audience, though not I suspect without the prompting of Chauvin, who in his note draws attention to the start of the development of the opening movement and its use all the notes of the chromatic scale, with the exception of G natural. Perhaps he might with better purpose have noted Mozart’s extraordinary use of chromaticism throughout the symphony; it is responsible for engendering much of the work’s tragic drama and is a prime feature that distinguishes it from many another turbulent G-minor symphony, including Mozart’s own earlier example, K 183.

Leading from the first violin desk, Chauvin’s way with Mozart is quickly established with the Don Giovanni Overture that opens the CD. His tempos tend to be on the brisk side, leading to a danger of brusqueness not always avoided. On the credit side, however, there is an inherent sense of drama, which is aided by splendid balance between strings and the exceptionally accomplished wind, and a keen ear for detail. The strings are not always a match for the wind and there is a trace of sourness in the Overture. One movement where greater forward momentum certainly does pay dividends is in the central Adagio of the A-major Piano Concerto, which without losing the depth of feeling the music conveys – some of the most profound even Mozart ever wrote – better conveys its siciliana rhythm and avoids the trap of sentimentality into which it sometimes falls. For the most part, this movement is also exquisitely decorated, as it must be if it is to be expanded from its skeletal state. It is to Staier’s credit that he mostly avoids the temptation to rewrite rather than ornament the melodic line, and only near the conclusion (from bar 88) do I feel he slightly over-eggs the pudding. Otherwise, Staier’s performance is marked by the nimble and precise finger-work that is a hallmark of his playing, with judicious touches of rubato underlining just how fine a musician he is.

The G-minor Symphony is given in the second version with clarinets, as is usual. Unlike the overture and concerto it was not recorded in the Arsenal de Metz – Cite Musicale but in the Notre-Dame de Liban church in Paris with a warmer, more generous acoustic (and a substantially differently constituted orchestra). It’s a fine performance – fine enough indeed to have wished that Chauvin had taken the second-half repeat of the finale, again illustrative of Mozart’s astonishing contrapuntal chromatic mastery, though a steadier tempo might have been more effective here. But all-in-all these are challenging and rewarding performances of familiar masterpieces that make the listener prick up his ears anew, not always a foregone conclusion.

Brian Robins