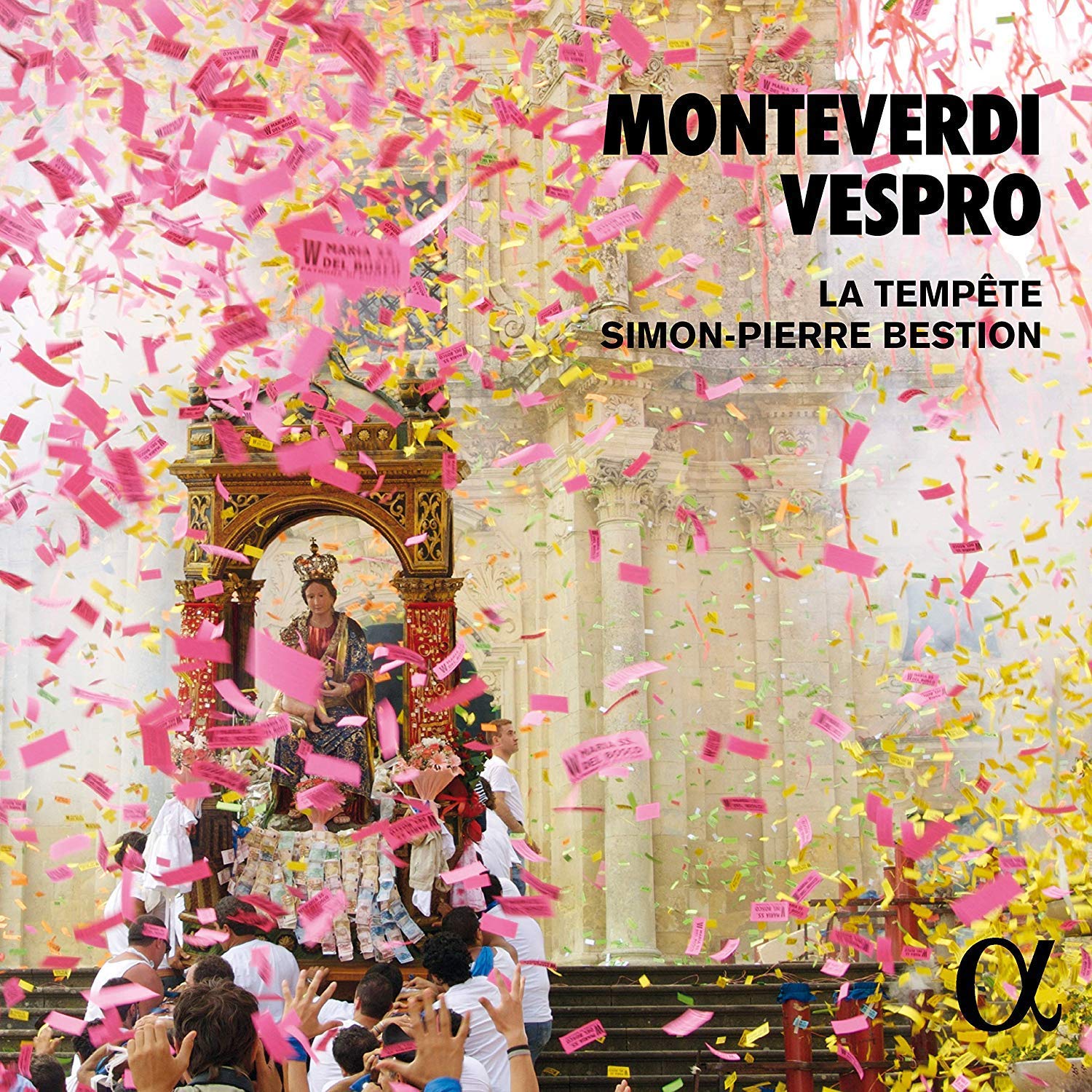

La Tempête, Simon-Pierre Bestion

142:07 (2 CDs in a card folder)

Alpha Classics ALPHA 552

This original take on the Monteverdi 1610 Vespers will not be everybody’s cup of tea, if only because the standard parts of the Vespers that people expect to hear are not performed to a standard that we expect in HIP recordings today – the vocal singing in the psalms for example has sopranos singing with a particularly ‘French-style’ vibrato, and his somewhat wayward scorings – adding and subtracting instrumental colour to illuminate a word here and there is more reminiscent of orchestration as practised by Berlioz or Elgar. Indeed, I have not heard such re-imagined scoring – albeit with period instruments – since I heard Walter Göhr conduct his edition in Westminster Abbey in 1959.

The main interest in this recording – and I have over a dozen recordings from the last two decades alone – must be in the juxtaposition of the supplementary material alongside Monteverdi’s. The opening Versicle and Response, set by Monteverdi to a re-worked version of the toccata that acts as a curtain-raiser to the Orfeo, is treated – as in that kind of modern cookery that presents a deconstructed rhubarb crumble for a pudding – as a series of elements. We have a rough falso-bordone version sung in a style that is a cross between how you might sing the naïve chant setings of Père Gouzes and the Dorset West Gallery tradition. Then follows the Toccata directly from the Orfeo, and finally the 1610 version with voices, strings and exotic wind, but no cornetti. The faux-bourdon settings he takes from an anonymous xvii century manuscript preserved in the Bibliothèque Inguimbertine at Carpentras in Provence. When asked whether the Vespers could have been sung in this way in the period when they were composed, Bestion replies in the dialogue interview that is his apologia, ‘No, not at all! This is a complete re-imagining, adding in instrumental parts, and also singing the same sections of text twice’. This recording is a newly imagined event, turning the Monteverdi Vespers into the framework for a liturgical happening underscored by childhood memories of summer holidays with the family, staying in a monastery and being overwhelmed by eves-dropping on the great monastic chain of prayer.

So after a plainsong antiphon, sung by a single voice in a way that has echoes of Near-Eastern monody, and a faux-bourdon setting from the Carpentras library, Dixit Dominus by Monteverdi begins with strings, the voices coming in as if they were vocal entries in a Gibbons or Hooper verse anthem. ‘I set about rewriting the instrumental parts’, he says, ‘. . . to reflect all the diverse colours of the orchestra.’ These arrangements are fine in a way: a string ensemble decorates the bare bars of the bass’s Gloria at the end of Dixit like an Purcell viol fantasia on a single note; and sometimes he repeats a section that he likes, as in the triple section in the Gloria of Laudate pueri, which he runs instrumentally first before adding the voices – but the vocal style chosen for the Monteverdi elements in this production seems to owe little either to the rougher faux-bourdon style – sometimes pitched unbelievably low as in the setting of Laudate pueri – or to the ‘supple, slightly androgynous voice’ of Eugènie de Mey. Instead they seem firmly anchored in a slightly dated style of singing that uses quite a lot of modern techniques, like a good deal of vibrato in the upper voices.

Modern in conception too is the treatment of the foundation instruments. Harpsichord, lutes, harps and organ are added and subtracted for effect, providing a degree of distracting restlessness that steals attention from the setting of the text. Tempi are varied for no apparent reason – in Laetatus sum the running bass motif, repeated a number of time before the Gregorian intonation is heard (instrumentally at first), is taken at a faster pace than the much slower even-numbered verses: where has the concept of tactus gone?

I found the ritornello, trilli and all, for a pair of trombones that opens Duo Seraphim before the tenors take over equally odd, even if it no longer surprised me. Nisi goes at a cracking pace, helped by the rhythm section of ‘a thousand twangling instruments’ – though I think Christine Pluhar’s L’Arpeggiata does that kind of excitement better.

The second CD opens with a ricercar by Fresobaldi on Sancta Maria ora pro nobis to introduce Audi cælum, which has some of the best singing so far till cornetti roulades introduce ‘omnes’, and we are galloping off in a breakneck tripla. Benedicta es begins with single voices, till the other singers, and then the complete chorus angelorum catch the theme and pick up their cornets and sackbuts.

Lauda has just brass for the two SAB choirs with the tenors’ intonation at the start, and I found the proportions in the Sonata convincing musically, if unjustifiable theoretically. Ave maris stella has a free version of the plainsong for verses 2 and 3, and a home-embroidered counterpoint for the ‘solo’ verses. Never was there such a self-indulgent flattened 7th in the Amen.

By contrast, the Magnificat was almost straight, except for a mesmerising triple echo in the Gloria. At last I began to see what Bestion was aiming for, though as readers who have persevered thus far will have gathered, it’s not the Monteverdi Vespro of 1610.

If you are anything like me, you will be intrigued and repelled in equal measure. So try and listen to a few tracks before you buy: it’s not exactly what it says on the tin!

David Stancliffe

Click HERE to buy this CD on amazon.co.uk