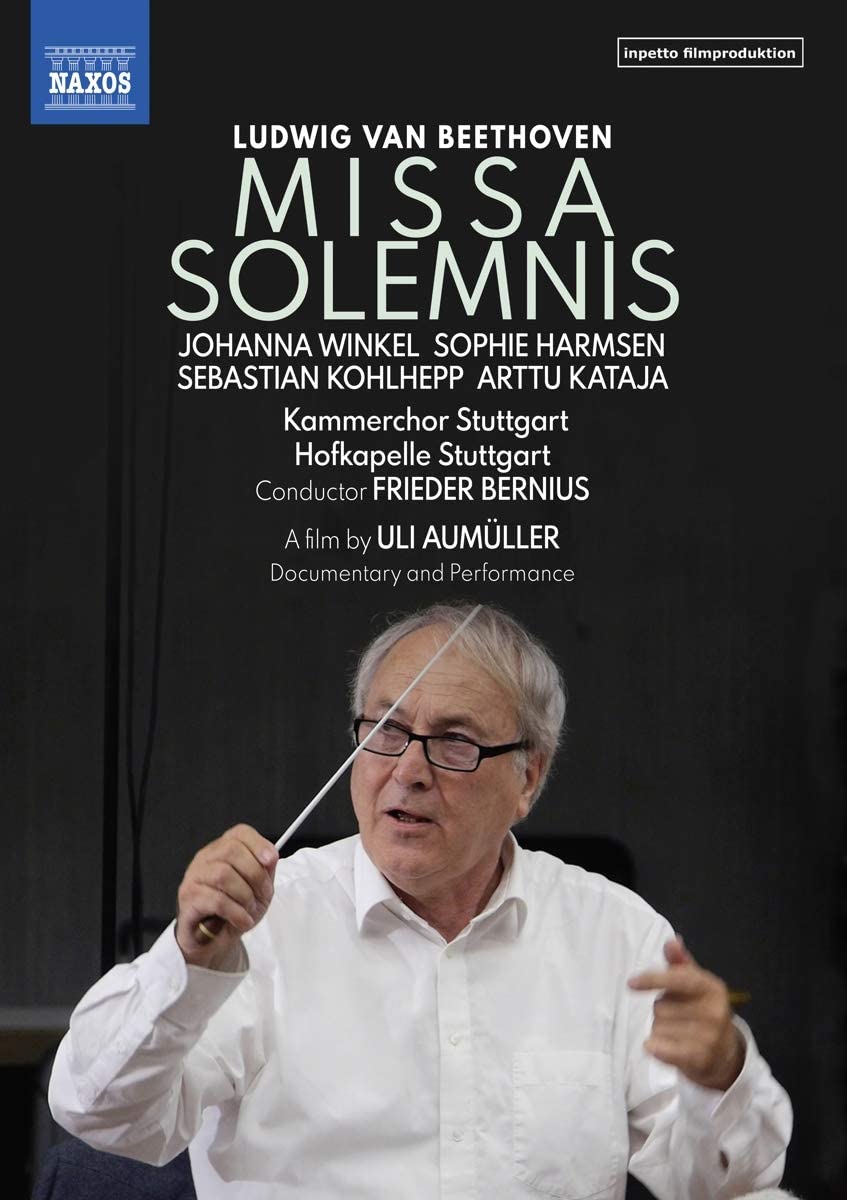

Johanna Winkel, Sophie Harmsen, Sebastian Kohlhepp, Arttu Kataja, Kammerchor Stuttgart, Hofkapelle Stuttgart, Frieder Bernius

Documentary and Performance

71:00 (music), 60:00 (documentary)

Naxos 2.110669

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

How do we approach the Missa Solemnis in this Beethoven year, 2020? It is not an easy question to ask of a work that is so multi-faceted, a huge structure that both storms the heavens, as if shaking a fist at fallen mankind, and yet also provides that same mankind with the solace and comfort of the Elysian fields. Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s first biographer, noted that from the start of the Mass’s long gestation period (1818-1823) Beethoven was in a condition of ‘oblivion of everything earthly’. The concept of a large-scale celebratory Mass for the elevation of his royal pupil Archduke Rudolf to cardinal and archbishop in Cologne Cathedral – an event long since over by the time the Mass was completed – had been transcended by 1823. I confess to finding it difficult to provide firm answers to the question posed in my opening sentence.

Some help is certainly provided by this new Naxos release featuring a film of a recording made in October 2018 at Alpirsbach Abbey, Baden-Würtemberg. Not only do we see film of the recording itself, but also a fascinating hour-long documentary that includes valuable insights into the work and Frieder Bernius’s approach to it. For that reason, I would recommend watching the documentary before viewing the performance. Bernius is, of course, a long-established conductor and was the founder of the Kammerchor Stuttgart, whose 50th anniversary is also celebrated by this issue. One of the most interesting features of the film is the way in which Bernius works with his choir, often taking just a couple of choristers to give them individual tuition on the work in hand. Even more compelling is to observe that Bernius’s approach, inspired by his many years of working on earlier choral music, is text-based, the results of his insistence on detailed working on such matters as pronunciation and articulation clearly evident in the final performance. In addition to the interviews and rehearsal clips, there are some fascinating archival clips of Bernius at work with earlier incarnations of the Kammerchor, along with interviews with some of the present performers.

Moving to the performance itself it is clear from the outset of the Kyrie that Bernius knows precisely what he wants. Taken at a measured tempo, the music moves with calm assurance, while the solo entries announce a fine young quartet that throughout impresses particularly in the many ensemble passages, obviously encouraged by Bernius to make the most of the madrigalian textures with which the work abounds. Christe is beautifully managed, though the timpani and brass don’t quite achieve unanimity in the quiet transition back to Kyrie. The Gloria, too, sets out at a well-judged tempo, avoiding the feeling of being pushed. Indeed, the whole, vast movement is unfolded by Bernius like an epic poem. ‘Et in terra’ brings a moment of wondrous stasis in the midst of powerful drive, while the prayerful ‘Gratias’ is another memorably placid interlude succeeded by some splendidly incisive orchestral playing in the lead back to the opening tempo and ‘Domine Deus’. And it is worth mentioning at this point that although the period-instrument Hofkapelle Stuttgart is hardly the most illustrious orchestra to undertake the Missa Solemnis, its playing throughout is excellent, with many distinguished moments coming from its wind section. The overall grandeur of the movement is brought to a triumphant peroration in the final doxology.

Credo opens as powerful affirmation, the contrapuntal passages once again luminescent in their clarity of detail. The start of ‘Et incarnatus’ finds the choral tenors handling this key moment with a real sensitivity complimented by glinting high wind, another treasurable moment. The stabbing pain of ‘Crucifixus’ is tellingly conveyed, as is the mesmerizingly lovely outcome at ‘et sepultus est’.

Beethoven’s ‘Sanctus’ is not the exultant triple cry of so many settings but a reverential moment on bended knee in contemplation of God’s glory. The choral sopranos have a rare ragged moment of ensemble at the exposed entry on ‘Osanna’, but in general cope with Beethoven’s wickedly high tessitura very capably. The high violin solo a little later is very well played. The opening of Agnus Dei provides a fine moment for bass Arttu Kataja, to distinguish himself and lead his three colleagues into a gloriously sung exposition, while the militaristic flourishes (first introduced into an Agnus Dei by Haydn in his Missa in tempore belli) provide thrilling moments of dramatic extroversion.

As I hope is clear from the foregoing Bernius’s Missa Solemnis impresses by dint of its total integrity. It may not be the most imposing or the most dramatically enthralling version on record, but few will not be moved and touched by it. ‘From the heart, may it go to the heart’, wrote Beethoven of his monumental work. Here that mission is unquestionably accomplished.

Brian Robins