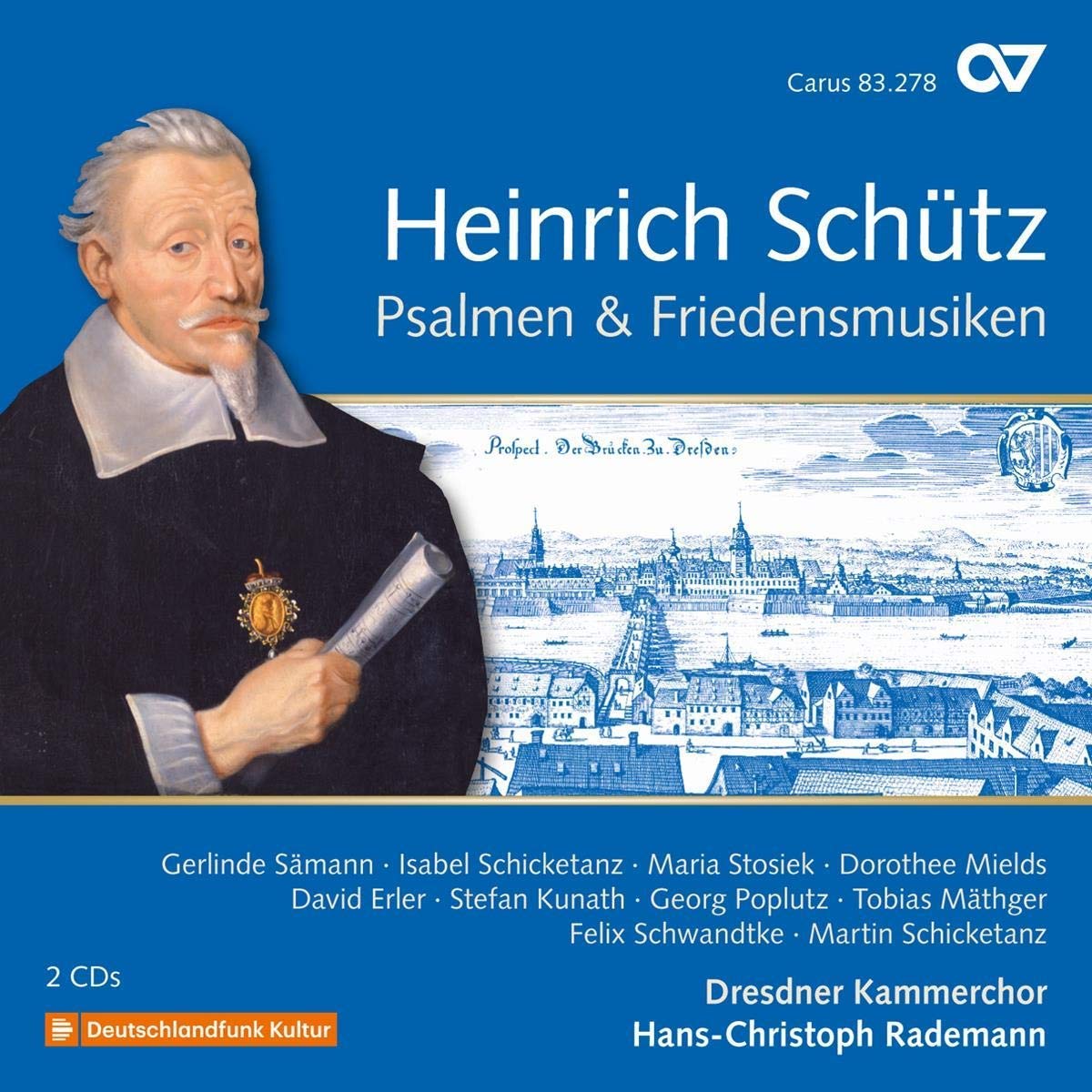

Complete recording, Vol. 20.

Gerlinde Sämann, Isabel Schicketanz, Maria Stosiek, Dorothee Mields, David Erler, Stefan Kunath, Georg Poplutz, Tobias Mäthger, Felix Schwandtke, Martin Schicketanz, Dresdner Kammerchor, Instrumentalisten, Hans-Christoph Rademann

138:05 (2 CDs in a box)

Carus 83.278

These two CDs mark the end of Hans-Christoph Rademann’s complete recording of Schütz in collaboration with the publishers Carus that began in 2006. CD1 includes a number of psalm settings (127, 15, 124, 137, 85, 116, 8 and 7) and the Whitsun Sequence, while CD2 has commissioned works for public occasions, a couple of biblical dialogues, and music of a more personal nature, like Schütz’s ode to his wife who died (aged 24) in 1625. The astonishing variety of music represented here alerts us to the significance of Schütz’s oeuvre spanning the long period of his life from the madrigals composed under the influence of his teacher Gabrieli in Venice, through the richly scored psalms of his early maturity to the biblical dialogues and solo songs, with their minimalist instrumental colouring, of his middle age and maturity, and also to the breadth of his commissioned work.

The team of singers for the single-voice performances of much on these discs is a starry double SSATB quintet with Gerlinde Sämann, Isabel Schickentanz, Dorothee Mields, Georg Poplutz and Tobias Mätheger among their number. Many have connections to the Dresdener Kreuzchor or Kammerchor, like Rademann himself, and the Dresdener Kammerchor here is a fine foil to the solo voices with whom they share the same timbre as the opening psalm, Nisi Dominus (SWV 466), reveals at once. Psalm 15 (SWV 473) that follows it has two contrasting cori, one of alto & bass with two violins and violone, the other soprano & tenor with three trombones. In Psalm 137 – By the waters of Babylon – the verses of lament are given to the chorus tenors with four trombones while those that tell of the hanging up of their harps are sung by two solo sopranos and bass with two theorbos and continuo.

By contrast, the four choirs in the Latin Sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus – two sopranos & fagotto, two cornetti & bass, two tenors & three trombones, alto & tenor with two violins & violone – are not all heard together till the opening chords of verse 4, when Schütz’s characteristic G major to E major shift illuminates the words O lux, and some bars of 6/8 invigorate the heavenly rewards promised. CD1 ends with Psalms 8 and 7 and some of the niftiest trombone playing I have heard amongst other delights. The balance between voices and instruments is excellent, and the ringing clarity of the whole ensemble makes these fine performances under the experienced and sure-footed Rademann.

On CD2, big public works like Da pacem and an immense setting of the Benedicite with a wide variety of instrumental accompaniment to colour the text contrast with the chamber quality of Tugend ist der beste Freund (SWV 442), the strophic Danklied (SWV 368) with its instrumental ritornelli and the solo song Mit der Amphion zwar (SWV 501) that Schütz wrote on the death of his wife. Especially interesting in this category of smaller scale works are the two biblical dialogues – the well-known Easter dialogue (SWV 443) Weib, was weinest du with pairs of soprano and tenor voices for the dialogue between Mary Magdalene and Jesus, and the enchanting Vater Abraham (SWV 477) with its sinfonias for pairs of violins with the rich man (B) and recorders with Abraham (T) probably dating from the 1620s and new to me.

The greater variety of styles shown in CD2 makes this pair of CDs as good an introduction to Schütz as one could imagine. This is not the sweep up of oddments that the final volume of a series often is. If you do not know the long-lived Schütz to be the major figure in German music in the 17th century, buy this volume and start from here.

David Stancliffe