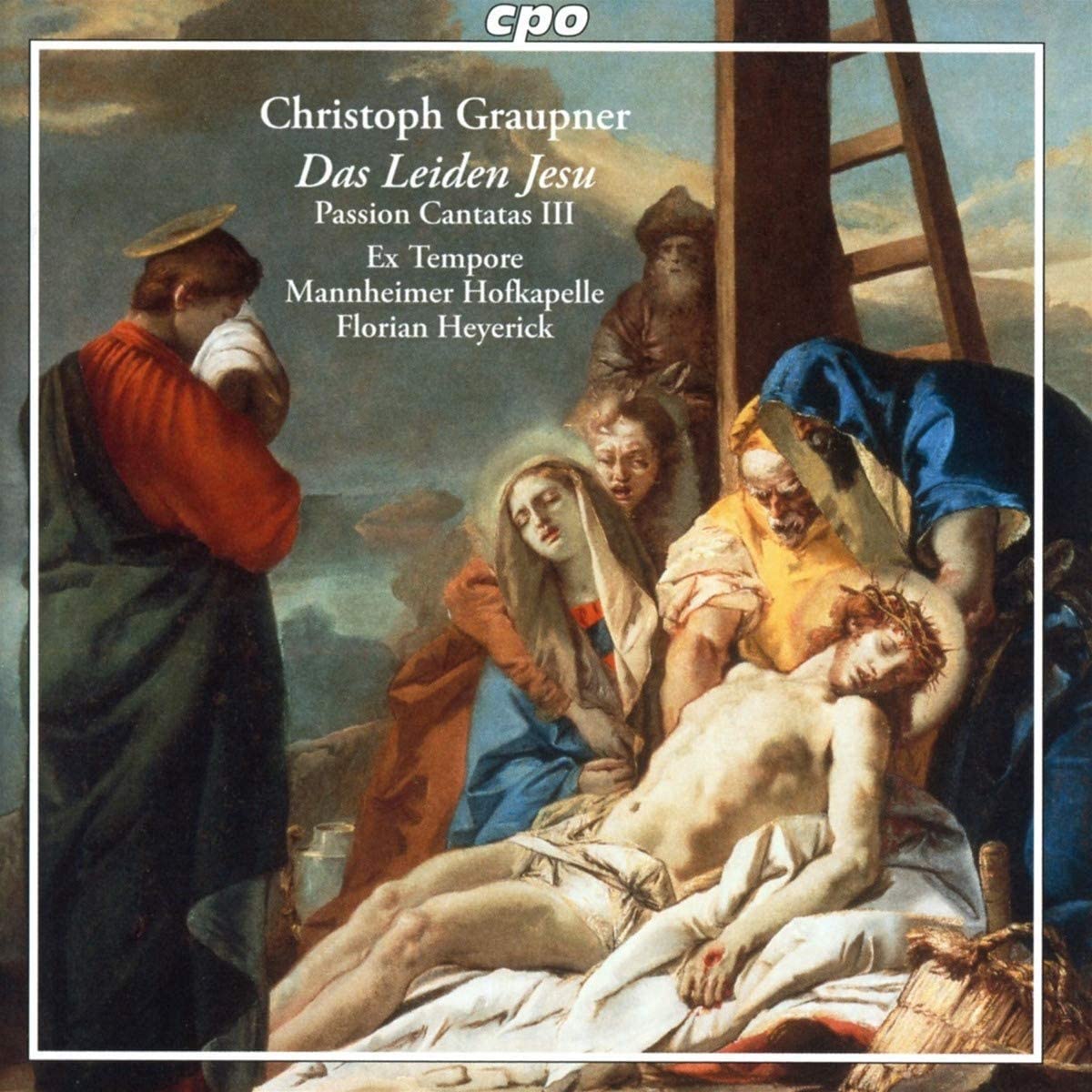

Passion Cantatas III

Ex Tempore, Mannheimer Hofkapelle, Florian Heyerick

69:27

cpo 555 230-2

GWV 1119/41, 1124/41, 1126/41

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

This is the third instalment of a series of selected Eastertide cantatas by Christoph Graupner to appear on CPO, based on the refined texts of the pastor, theologian, polymath Johann Conrad Lichtenburg (1689-1751) who besides interests in philosophy, mathematics, astronomy and architecture, was a very gifted religious poet – librettist, who wrote some 35 annual cycles, I. e., over 1500 sacred texts! He studied at Leipzig and Halle, the latter a bastion of pietism, which took hold in Germany in middle of the 18th century. Of the 1400 extant Graupner cantatas, some 1190 are from the most able quill of J. C. Lichtenburg; obviously a fruitful collaboration was at work! These cantatas from the 1741 cycle described as “Betrachtungen” (contemplations/reflections) on the circumstances surrounding the “Versöhnungsleiden” redemptive/propitiatory sufferings of our Saviour. The definition used here for “Reflections” shows alert respect for the prevailing Passion-oratorio format, and feels equally influenced by the text of B.H.Brockes’ Passion-oratorio set by many composers of the age; there are also hints of the other famous theologian, librettist, pastor Erdmann Neumeister (1671-1756) who had previously helped shape the incipient cantata for.

The CD opens with the work for the last Sunday (Estomihi) before Passiontide itself, with some strikingly original strokes of declamatory expression, more akin to an actual Passion’s chorale workings than a mere cantata. Some very bold, original writing, one might say in a hybrid style?

Not only are the thematic details well-observed with pertinent word-painting, but the attention to deftly applied instrumental colours depicting each of the subsequent tableaux, is most befitting, from two oboes, strings* and continuo in GWV1119/41, next we have flute, two oboes, bassoon and strings in GWV1124/41, and finally flute, three oboes and strings in GWV1126/41; the oboes are richly sonorous and plaintive.

At turns these works feel conventional, then surprise with clever twists, almost in a casual, experimental way, yet never straying far from elegiac or edifying. The chorales deserve a special mention, coming across as beautifully woven final flourishes; as with the famous last one on the CD (O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig am Stamm des Kreuzes geschlachtet). With more explorations of Graupner’s cantatas, we are beginning to see why he was indeed a worthy choice for the Leipzig post in 1722, and why his employer, the Landgraf of Hessen-Darmstadt, wanted to hold onto him. Florian Heyerick is a very alert and sensitive conductor, bringing the very best out of his choral and instrumental forces; the sopranos and basses seemed to me to really shine and excel.

This is a warmly recommended, third instalment of the Graupner/Lichtenburg cycle for Easter 1741 with some noteworthy additions to the Passiontide repertoire.

David Bellinger

(*Graupner specifies “Violette”, possibly a smaller member of the viola family; the Mannheimer Hofkapelle use violas)

NOTE: Apologies to the performers, the record company and the reviewer; this somehow fell through the cracks and is being published A YEAR LATE! Keen fans of Graupner may already have the 4th instalment in the series, since cpo released that to coincide with Easter 2020!