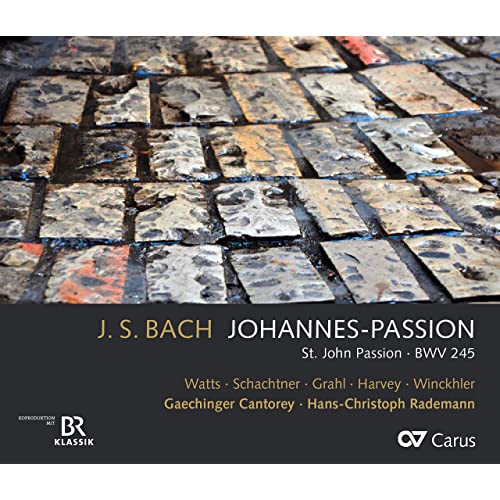

Elizabeth Watts, Benno Schachtner, Patrick Grahl (arias & Evangelist), Harvey (Christus), Winckhler (arias & Pilatus), Gaechinger Cantorey, Hans-Christoph Rademann

108:03 (2 CDs)

Carus 83.313

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk as a mp3

Rademann makes the central chorale – Durch dein Gefängnis – in the key of E major the dividing point between the two CDs in his recording of the 1749 version of the John Passion which is intelligent theologically, as it is the hinge point in the central section of Bach’s Johannespaßion. But this means we miss the immediate pick-up by the Evangelist of Die Jüden aber schrieen that leads us into the chorus Lässest du diesen los and reveals the chiastic structure of Bach’s setting of the trial before Pilate. This central section hinges on the questions of Jesus’ origin – where does he come from? can he really be a king? and how can a man who is bound seem so free? – while he displays such surprising calm when confronted by the crowds baying for his blood. This is where the structural dilemma for conductors of the John Passion is laid bare: with the very unequal division of material between parts I and II, how do you best arrange it on a pair of CDs when theologically it falls into three sections?

Rademann has just finished his complete Schütz, which is exemplary in terms of HIP, where the right vocal forces are matched with elegant instrumentation. However, this performance of the 1749 version is a bit more in the old-style German mode, with 5.4.3.2.1 strings, 2 harpsichords and the contrabassoon to match the newly named 25-strong Gaechinger Cantorey. A photograph of their John Passion in last year’s Bachwoche in Ansbach shows them stacked behind the instrumental ensemble, with the Evangelist, Christus and aria singers – a different bass singing Pilatus and the arias – seated at the side and taking no part in the choral numbers, but ready to step out and stand in front of the ‘orchestra’ as soloists.

The opening chorus feels a bit slow with its four heavy beats: not even the middle section can feel two in a bar. And the suspensions in the flute and oboe parts are only just sufficiently audible above the massed strings and voices. This solidity extends into the succeeding section, where the narrative – beautifully sung by the excellent Patrick Grahl, an ex-Thomaner and as good in the arias as in his clear and well-enunciated Evangelista – is punctuated by massive chords on the harpsichord and even the 16’ at times as well as the ‘cello and organ. Peter Harvey is a magisterial and well-honed Christus while Matthias Winckhler takes Pilatus and the bass arias. He is a good foil for Peter Harvey, and the interchange with Jesus at the heart of the central section is very powerful dramatically.

The organ is a copy of a small organ by Gottfried Silbermann made for the Bachakadamie Stuttgart, and has more principal tone than we are accustomed to, which is a plus, but adds to the solidity of the narrative, where chords are often held long.

The chorales are performed four-square, with pauses at the end of the lines, and the whole manages to convey the rather late Baroque feel of this latest version of John Passion, with its occasionally specific changes not only to the texts but to the scoring – the contrabassoon, the muted violin not only in the Betrachte and what now becomes Mein Jesu, ach! rather than Erwege but also playing with the traverso in Zerfließe. The choice of Elizabeth Watts as the soprano is probably reflected in this desire to go for a later sound. Her vibrato is enormous in Zerfließe, though it is more restrained in Ich folge, where the heavy bass line is particularly noticeable. The dramatic possibilities are fully exploited at the end, where Ruht wohl dies away to very little, and then the final chorale crescendos right through.

So this will not probably become a favourite version of those who like the leaner sound associated with a more pared-down version of the earlier scoring and where the aria singers, the Christus and Evangelista are all part of the choro. But thorough-going 1749 versions are a rarity, and we should be grateful for this committed performance which gives a real insight into the developments in the late Baroque sound-world as it comes closer to the classical tradition in which so many people have experienced their Bach.

David Stancliffe