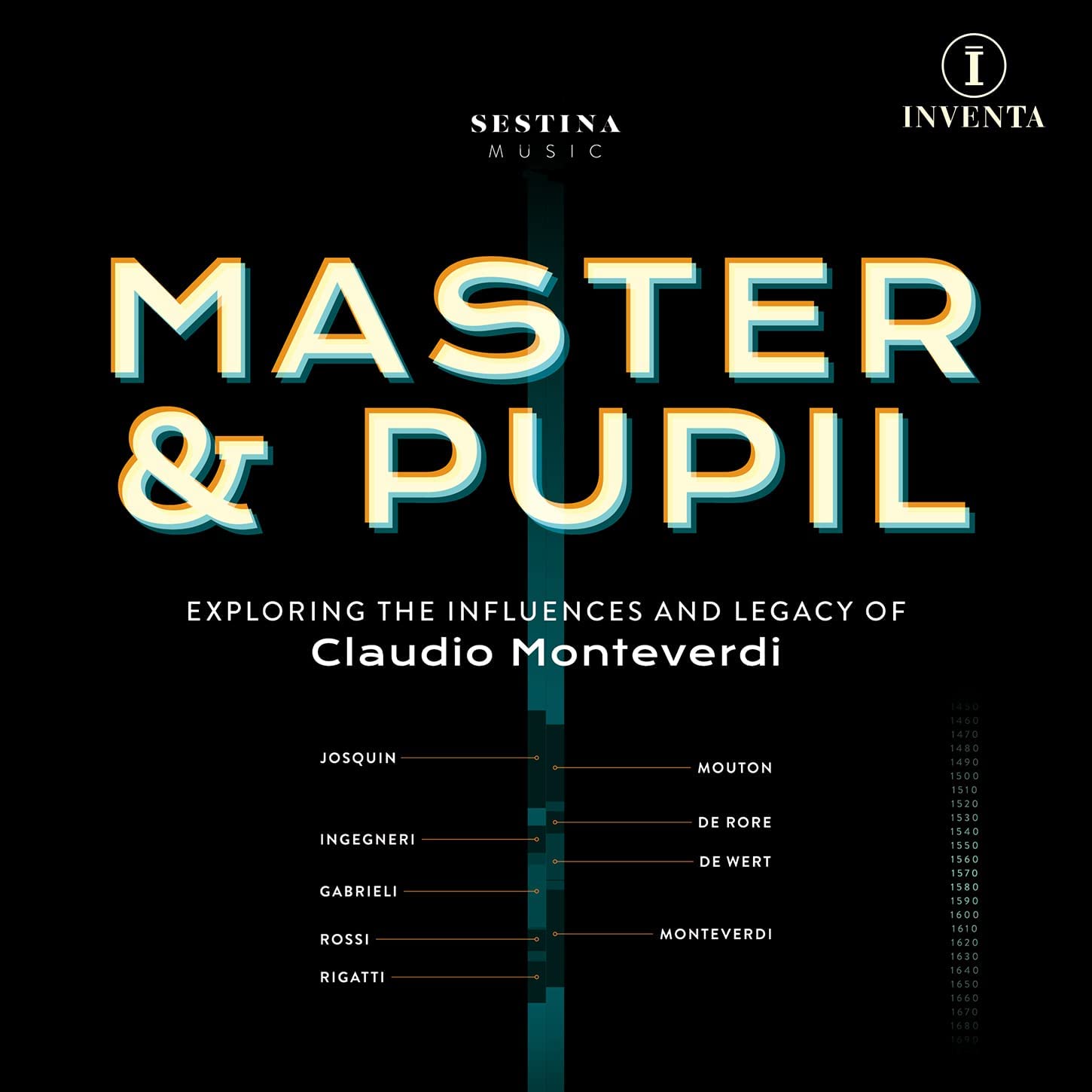

Exploring the influences and legacy of Claudio Monteverdi

Sestina Music, Mark Chambers

71:18

resonus Inventa INV1007

Click HERE to buy this recording on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links keep this website FREE TO ACCESS]

This is an interesting CD, exploring both the influences on and the legacy of Claudio Monteverdi. So, as well as music from Scherzi Musicali of 1607 and Selva morale of 1640/1, it contains music by Josquin, Mouton, de Rore, Ingegneri, Andrea Gabrieli and de Wert from among those who influenced him and by Rossi, Rigatti and Giovanni Gabrieli whom he may, in turn, have influenced himself.

There are 18 singers – frequently singing several to a part, while the instrumentalists are two violins/violas, violone, two cornetti, two sackbuts and a dulcian, with chitarrone/guitar, harp and organo di legno. In music like the Dixit secondo from 1641, the scoring is enriched by sackbuts, and the dulcian is given characterful obbligato lines to play. The scoring is modest, and elegant, and is played by our best practitioners: Oliver Webber and Theresa Caudle, violins, Peter McCarthy, violone; Gawain Glenton and Conor Hastings, cornetti, Emily White and Martyn Sanderson, sackbuts; William Lyons, dulcian, with Paula Chateauneuf, theorbo and guitar, Aileen Henry, harp and Jan Waterfield playing Walter Chinaglia’s organo di legno from the English Organ School at Milburne Port. Details of all the instruments are in the booklet, and for the Chinaglia organ, see the review of his project that I wrote for EMR in 2019.

The choice of this particular organ is significant, as the singing quality of the open wooden principal pipes is important in encouraging singers to create the right sounds for the music of the first half of the 17th century. And that is the key to this CD. When I heard the first track, I thought: ‘ Oh, no: here we go again,’ as, after an elegant string sinfonia, multiple voices burst in with a rumbustious balletto – De la bellezza from Scherzi Musicali – in the beer-cellar style. I should have had more faith in Mark Chambers, since this balletto was followed at once by some ravishing singing from the upper voices of Josquin’s Recordare Virgo Mater in quite a different style. Trained upper voices do not always find it easy to eschew their singerly tendency to use vibrato on unexpected notes, but there is a genuine and interesting attempt here to match vocal timbre to instrumental, even if I am rarely convinced by the vocal doubling Chambers uses.

The two Rossi instrumental pieces are exquisitely played, but the most instructive part of the disc for me was the juxtaposition of the sections of the extraordinarily rich and colourful Mass by Giovanni Rigatti (written at the age of 27 and antedating the publication of Monteverdi’s Selva morale by six months or so) with Giovanni Gabrieli’s 10-part Maria Virgo from 1597. Rigatti has an interesting comment on instrumental doubling, which I’d like to see in context – and in Italian (I suspect ‘gentle’ is a mistranslation):

… the gentle musician who finds himself with the proportionate

number of voices and instruments is advised to double the parts …

so that they will be more melodious and harmonious

This is a well-prepared and meticulously researched CD. But it is much more: these are really good performances and should help practitioners to understand more about how to balance voices and instruments in this period. I recommend both the scholarship and the performance to as wide a range of listeners and performers as possible.

David Stancliffe