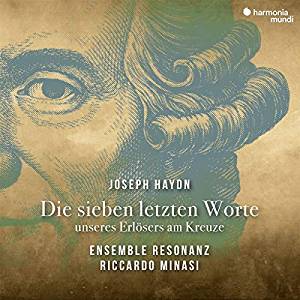

Ensemble Resonanz, conducted by Riccardo Minasi

63:56

harmonia mundi HMM 902633

Haydn explained the genesis of his Die sieben letzten Worte in a letter to his biographer Griesinger: ‘About fifteen years ago [1786] I was requested by a canon of Cádiz to compose instrumental music on (The Seven Last Words of our Saviour on the Cross) […] After a short service the bishop ascended the pulpit, pronounce the first of the seven words […] and delivered a discourse thereon. This ended, he left the pulpit and prostrated himself before the altar. The interval was filled by music […] the orchestra following on the conclusion of each discourse. My composition was subject to these conditions, and it was no easy task to compose seven adagios lasting ten minutes each […]; indeed, I found it quite impossible to confine myself to the appointed limits’.

Haydn’s words are interesting in a number of respects, not least for showing that, like the sections of the Mass, his movements were originally interspersed by discourse and ceremony. The problems arising from a succession of slow movements were therefore mitigated by the performance conditions. The composer also provided more variety than he suggests by subtly varying tempi, only two movements (the Introduzione and no. V) being marked Adagio, while no fewer than four (no’s 2,5,7 and 8) are largos, in the 18th century a quicker tempo than adagio. Despite Haydn’s misgivings about its structure he came to view The Seven Last Words as one of his most successful works, a viewpoint seemingly shared by many of his contemporaries given that it was quickly taken up throughout Europe after its publication in July 1787. Just a month later Haydn published an arrangement for string quartet, it also appearing at the same time in a version for piano, while some years later the composer adapted it as an oratorio for soloists and chorus.

In modern times it is strangely the string quartet version that has found the most favour and indeed a glance at the record catalogues shows that there are more versions of it currently available than there are of the orchestral original. The Ensemble Resonanz is an orchestra that uses modern instruments with the objective of achieving historically informed performances. In some respects they do so to a remarkable degree, the strings played with very little vibrato that thus helps to achieve clarity and balance with the excellently played wind instruments. Ultimately there will always be tell-tale passages where the absence of gut strings is noticeable, as in no. 4 (Deus meus, deus meus; My God, my God) where both violins and violas take on a glassy sound not helped by the sentimentality encouraged by Riccardo Minasi. This tendency to mannerism, not the first time in my experience with this conductor, is regrettably one of the most salient characteristics of the performance. Much of it stems from the widest dynamic range I think I’ve encountered in 18th-century orchestral music. Even at quite a high volume, the sound covers a gamut from a barely audible whisper of sound to the violent assault on the ears in the trenchantly played evocation of the earthquake that followed Christ’s death, the brief movement with which Haydn concluded the work. Such extremes are incorporated into Minasi’s tendency to adopt fluctuating tempi. The overall impression is that the conductor is continually trying to make points, too often creating a fragmentary, disjointed approach that undermines the natural flow and phrasing of the music. All this is a pity, for there are many passages played with sensitivity and understanding that suggests a love for the music. Notwithstanding this and while also allowing for first-rate sound, the performance of this deeply moving and affecting work is too wayward to provide lasting satisfaction

Brian Robins