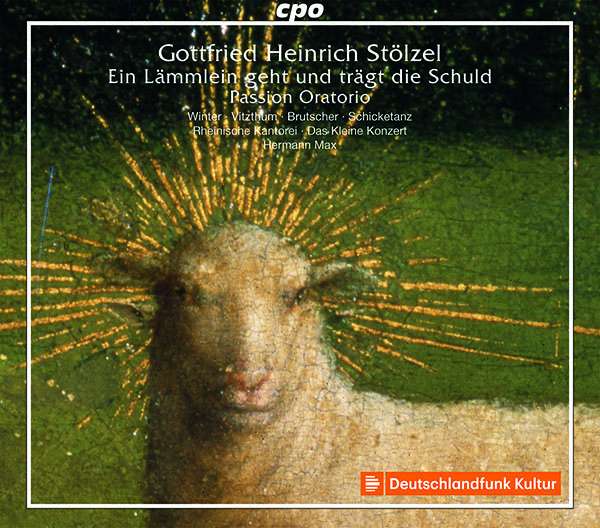

Veronika Winter, Franz Vitzhum, Markus Brutscher, Martin Schicketanz, Rheinische Kantorei, Das kleine Konzert, Hermann Max

cpo 555 311-2

110:28 (2 CDs)

It is hard to underestimate the widespread influence of the powerfully evocative and image-laden libretto known as The Brockes-Passion!

Conceived by B. H. Brockes (1680-1747), the Hamburg statesman and poet, andpublished c. 1712, with various settings by several noteworthy composers of the day, Keiser, Mattheson, Telemann, Handel, Fasch and Stölzel; even Bach’s St John Passion contains several elements, as did Telemann’s early Hamburg Passions of the 1720s, sadly lost.

In 1992, great efforts were made to reconstruct Bach’s musical library, and the music of G. H. Stölzel appeared terribly under-represented, save the famous aria “Bist Du bei mir” from the Notenbüchlein for Anna Magdalena Bach. Gifted musically from a tender age, Stölzel was a Leipzig student in 1707, active in the Collegio Musico. After some private tuition, he made an Italian tour, meeting famous masters. After working in Gera and Bayreuth, (the latter a centre for early opera), then from 1719 was court kapellmeister in Gotha, gradually turning his hand from operas to sacred music. And so we find the setting of a passion-oratorio circa 1720, not long before he set the Brockes Passion in 1725. It has also been discovered that a cantata cycle (on texts by Benjamin Schmolck) was performed by Bach in Leipzig 1735-6, and Stölzel’s earlier 1720 Passion-oratorio on Good Friday 1734.

Much of Stölzel’s musical legacy was neglected and destroyed, in part due to Georg Benda’s careless disregard for it. Hermann Max is to be most heartily congratulated for diligently compiling the score from parts found in the Schloßmuseum Sonderhausen; Bach obviously admired the music, since he re-worked the aria from the 13th Betrachtung: “Dein Kreuz, o Bräutigam meiner Seele” into “Bekennen will ich seinen Namen” from BWV200.

As per usual Hermann Max has drawn a fine team of performers around him, and the main soloists give a good account of themselves. For an early example of a Passion-oratorio, with 22 Betrachtungen (Contemplations) and 20 Chorales (all with clearly defined sources), it lacks the dramaturgic fluency of the Brockes Passions and others I can think of, yet does include passages for “Christliche Kirche” and “Gläubige Seele”, the latter acting like a kind of accompagnato leading into the reflective arias. Some of these arias (for example, tracks 6 and 12) exude a style close to that found in Graun and Telemann’s Der Tod Jesu (1755), yet others feel lacking in their overall effect and intensity, somewhat “underpowered”, given the vivid and descriptive wording. One senses an active, refined musical (operatic) mind at work, however, the musico-poetic grasp isn’t always alert or activated; nor is the broader instrumental palette. The Evangelist here gives a very good narrative link, using a device termed: Historic Present. The Duet of Gläubige Seelen (21) is rather fine, yet short-lived. The narration up to the lovely Aria “Allerhoechster Gottessohn” (27) seems a fairly weak response to the drama; so too the Aria (30) “Cease, ye murderous claws”! Finally, in the aria (33) we have some sensitive and emotive instrumentation, as the composer deploys a flute, yet it is again all too short-lived!

CD2 opens with the tenor aria that Bach used, yet in my very honest opinion, the following numbers for alto and soprano are musically far superior; indeed, Veronika Winters contributions here are truly noteworthy and soar aloft! So too the chorus before the final section stands out. The closing sections are most effective, being woven around the famous chorale, O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid. This actually feels more like a liturgical Passion with a few extra twists, than a Passion-oratorio. Every new Passiontide work should be judged on its own merits; alas, due to the sheer dominance of just a handful of works at Easter, many will fall foul of deep-rooted routines and certain perceived expectations, which is disappointing, as so many works will not even get to see the light of day, being held at bay until some fortunate discovery allows the spirit of these pieces to be heard alongside the more familiar. Hermann Max has once again presented on CPO another noteworthy Eastertide Passion, which is an historic document of finest musicology in action.

David Bellinger