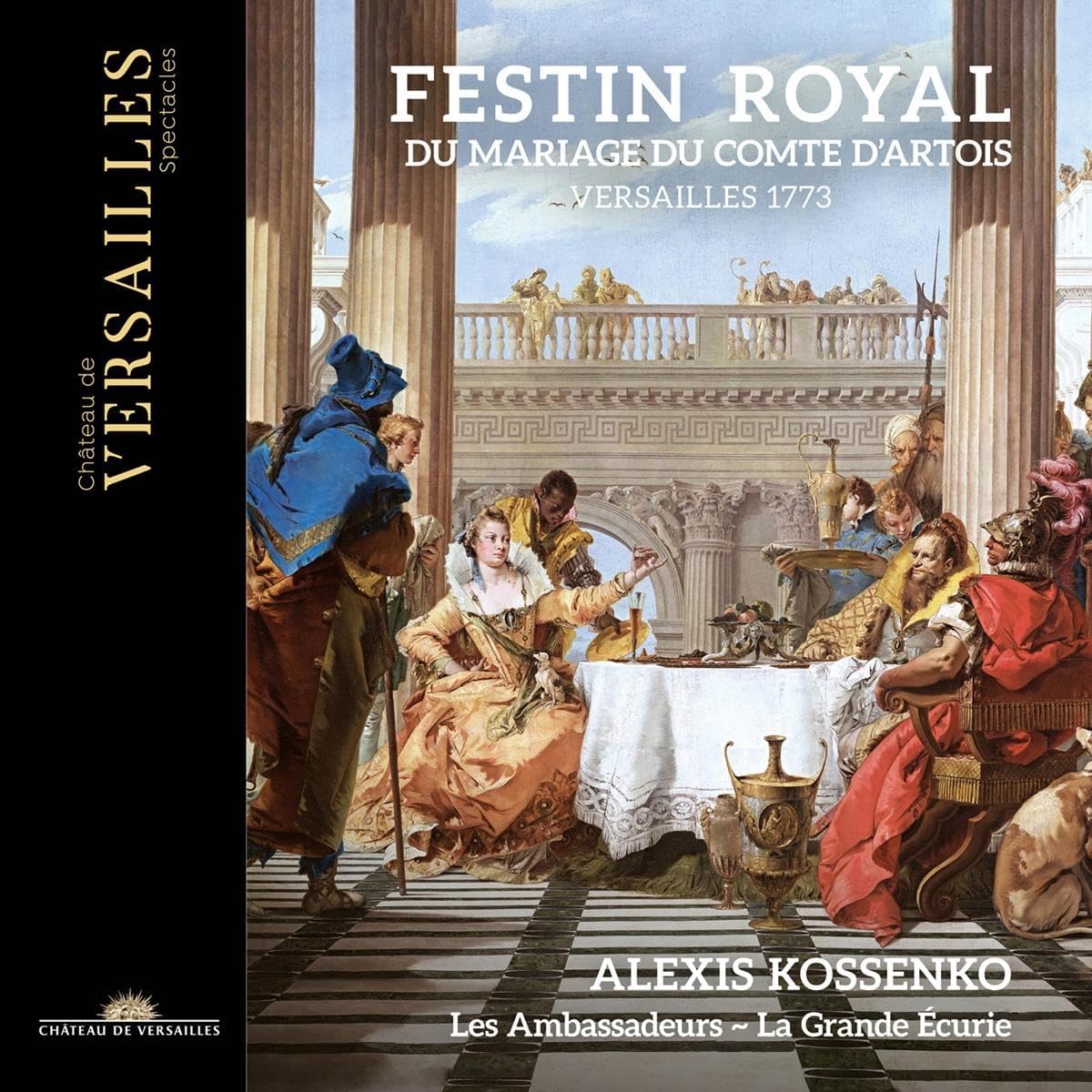

Les Ambassadeurs – La Grande Écurie, conducted by Alexis Kossenko

125:56 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Château de Versailles Spectacles CVS101

Following its completion in 1770 the magnificent Opéra Royal in the palace of Versailles played host not only to opera but also to large-scale court events such as weddings, banquets and balls. In fact, the day of its inauguration witnessed such an event in the form of the marriage of the Dauphin, the future Louis XVI, to Marie Antoinette, the youngest daughter of the Hapsburg Empress Maria Theresa. This was followed by a performance of Lully’s Persée. Three years later, having hosted the wedding celebrations of Louis XV’s next-in-line successor, the Count of Provence in 1771, came the marriage of the Count of Artois. As with all these sumptuous proceedings, music played an important role in the banqueting, in 1773 under the auspices of the current Surintendant de la Musique de la Chambre du roi, François Francoeur.

In contrast to previous incumbents, Francoeur did not write special music himself. Rather in conjunction with his close collaborator François Rebel he produced four suites for the occasion, utilising music taken not only from his works, understandably the lion’s share, but also successful operas by such as Rameau, Royer, Dauvergne, Mondonville and composers whose names are today less familiar: Pierre-Montan Berton (1727-1780), René de Galard de Béarn, marquis de Brassac (1698-1771) and Bernard de Bury (1720-1785). One of the fascinating aspects of the music included is not only how much of it is not recent, but also the number of works added to existing classics by the likes of Lully and Campra. Thus we have additions by Francoeur and de Bury for productions in 1761 and 1770 respectively of Lully’s Armide, providing a rare example at this time of a secular canon of works having become established as repertoire.

There are two particularly striking aspects of this recording produced at Versailles. The first is that the four suites are a rare example of music being performed in the exact location in which they were originally given. More fascinating still is that the performing forces were determined from a contemporary document that lists the number of instrumentalists that took part. From that, we learn that the orchestra consisted of 70 players, including 26 violins, six violas, no fewer than 14 cellos, four oboes, six bassoons, four horns and, interestingly, a pair of historic clarinets made in France. The results of putting together this large band are stunning, every bit as exciting as hearing Handel’s big occasional pieces played by the forces originally intended. As conductor Alexis Kossenko eloquently puts it: ‘This indulgence turned into exhilaration when we played the first notes of Francoeur’s overture [an addition to that from Lully’s Armide for a 1745 or 1761 production] … The density, the richness of the sound, the robustness of the attacks, but also the mellowness afforded by the 50 or so strings … All of this suddenly made sense, revealing the grandeur of this repertoire, royalty that asserts itself as much in magnificence as in grace …’ Both magnificence and grace are abundant in these splendidly played performances (well, I suppose the horns have their moments, but that’s all part of the fun) which far from being routine or dutiful exude an irresistible verve and character.

It would be pointless to spend much time discussing individual tracks. It’s not that kind of issue and in any event there are too many items, over 40. But a few observations. To get a taster of the visceral excitement that frequently leaps from these CDs try Royer’s Chaconne from his Pyrrhus of 1730, relishing especially the episode with the cellos and basses chugging energetically away. That’s just one of four chaconnes, a magnificent form that I have to confess having a particular weakness for. The one by Berton, an addition to Iphigénie en Tauride, Desmarest’s 1761 production of Campra’s 1704 opera, is a noble, stirring structure running to some nine minutes. Although almost forgotten today, Berton enjoyed a high profile in French musical life, being joint director (with Jean-Claude Trial (1732-1771), also represented here) and then general administrator of the Opéra, in addition to taking on the directorship of the Concert Sprituel, the famous concert-giving organisation. One final thought. As is proved by this hugely enjoyable issue, 18th-century France was not short of fine composers, but one name obstinately stands out as a great one. That name? Jean-Philippe Rameau, of course!

Brian Robins