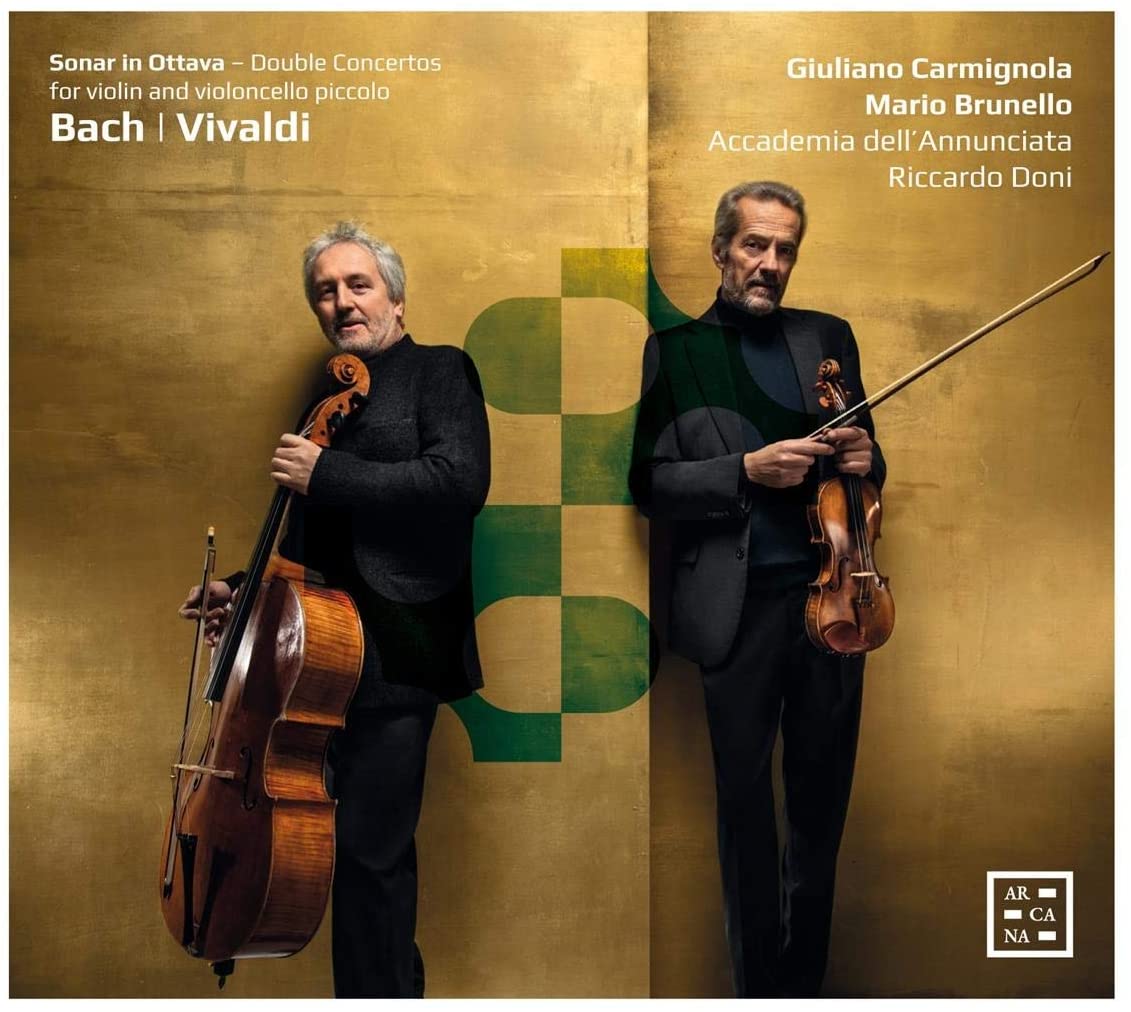

Double Concertos for violin and violoncello piccolo

Giuliano Carmignola, Mario Brunello, Academia dell’Annunciata, directed by Riccardo Doni

69:58

Arcana A472

I admire Mario Brunello and Giuliano Carmignola, and their playing, together with that of the Academia dell’Annunciata is elegant and stylish, but I cannot pretend that I like these fine concerti played with the solo instruments playing in different octaves.

Unlike the sonatas for viola da gamba and harpsichord, or some other of Bach’s works which he clearly arranged and rearranged for different combinations of instruments, I find that the intertwining and tossing to and fro of melodic lines at different octaves distracting and unappealing. This is particularly the case in the D minor double violin Concerto BWV 1043. In the opening vivace, the violin line doubled at an octave below just sounds un-Bachian to me, and quite unlike the only other instance I can think of where there is something similar – the central section in D major of the alto aria in the Johannes-passion, Es ist vollbracht. It is like a baritone singer doubling ‘the tune’ an octave lower in a four-part SATB chorale. In the middle movement, too, the canonic writing with its intersecting and overlapping lines surely needs instruments at a similar pitch? In other concerti, even when there are earlier versions of what Bach later presented as concerti for two or more harpsichords, a distinction in timbre as in BWV 1060 has often been reconstructed as a concerto for violin and oboe for example – but always by instruments in the same octave.

The reimagining of the music for these two instruments is served better by the less melodically variegated music of Antonio Vivaldi, with its highly arpeggiated figuration. Here, difference of texture sometimes provides a welcome variation to the texture.

The two colleagues, whose musical friendship goes back a long way, have – I suspect – been seduced by the intriguing possibilities of Brunello’s new violoncello piccolo, strung exactly an octave below the violin, on which he played the Sei Soli for violin so plausibly last year.

But, while you might be curious to hear what their concerti at an octave sound like, I doubt if you will want to keep this CD in your library.

David Stancliffe