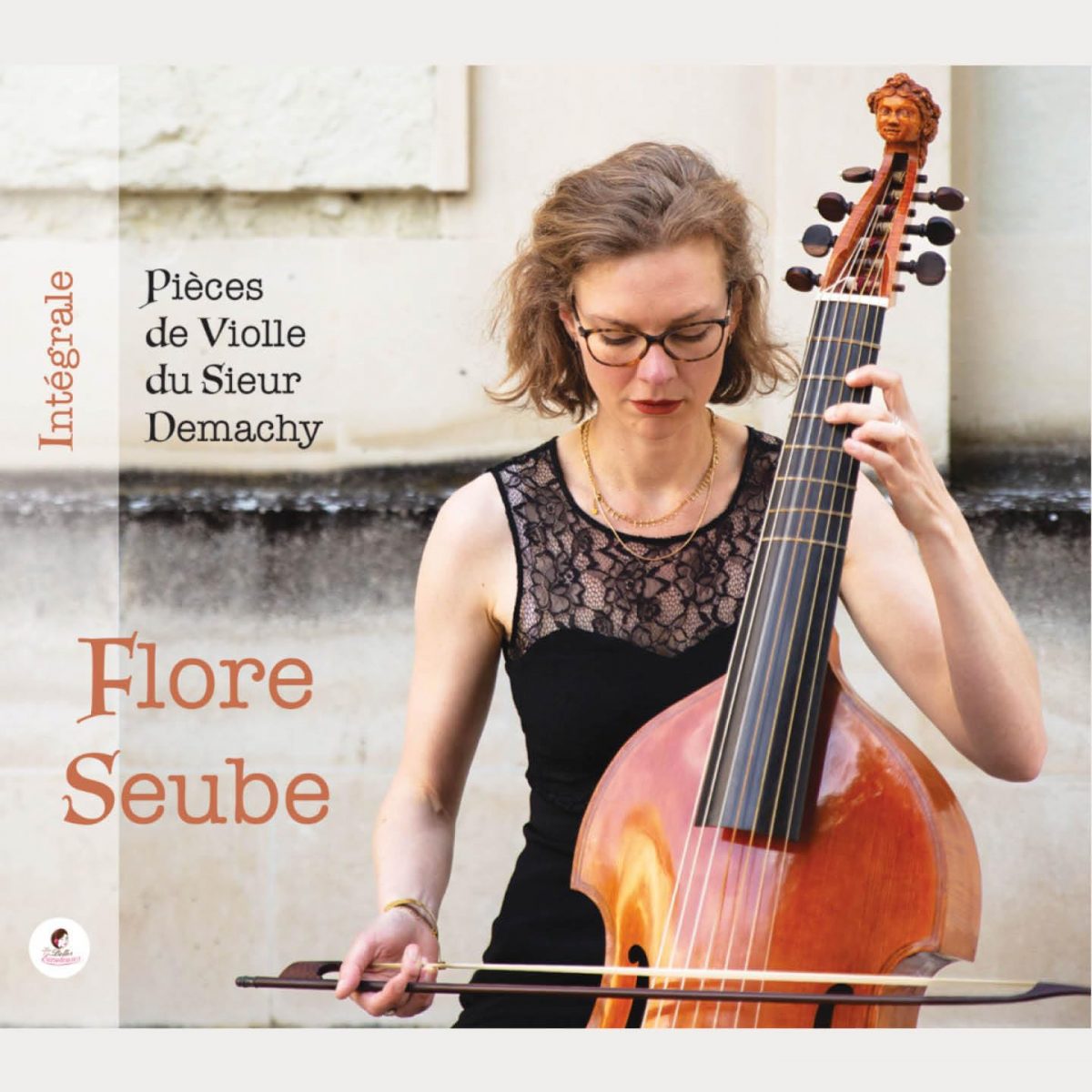

Flore Seube

119:55 (2CDs in a card triptych)

Les Belles Ecouteuses LBE 82

This complete account by Flore Seube of the surviving viol music of Sieur Demachy, eight suites in all on two CDs, is a world premiere of this evocative repertoire from the reign of Louis XIV. Demachy, a contemporary of Sainte-Colombe and Marais, has left us only this single collection of music, although its authoritative voice and unerring creativity suggest that much else has been lost. Ms Seube plays a wonderfully resonant seven-string bass viol by Pierre Jacquier in the generous acoustic of the Gîte de Lavaud Blanche, which enhances the instrument’s rich timbres without any loss of clarity. She treads a fine line between affectation and expression to produce eloquent readings of this rich repertoire. Each Suite comprises exactly seven movements, generally following the standard form of Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Gigue, Gavotte and Minuet, with one Suite only replacing the final Minuet with a quirky Chaconne. Sieur Demachy is at his most imaginative in the slightly freer Preludes, and Flore Seube adopts a suitably more exploratory approach in these, following the composer’s imaginative musical journey. However, this is consistently engaging repertoire deserving of wider attention, and Flore Seube has done both Sieur Demachy and her listeners a valuable service in providing these fine performances. A translation of the French programme notes printed in the booklet is available on the Belles Ecouteuses website.

D. James Ross