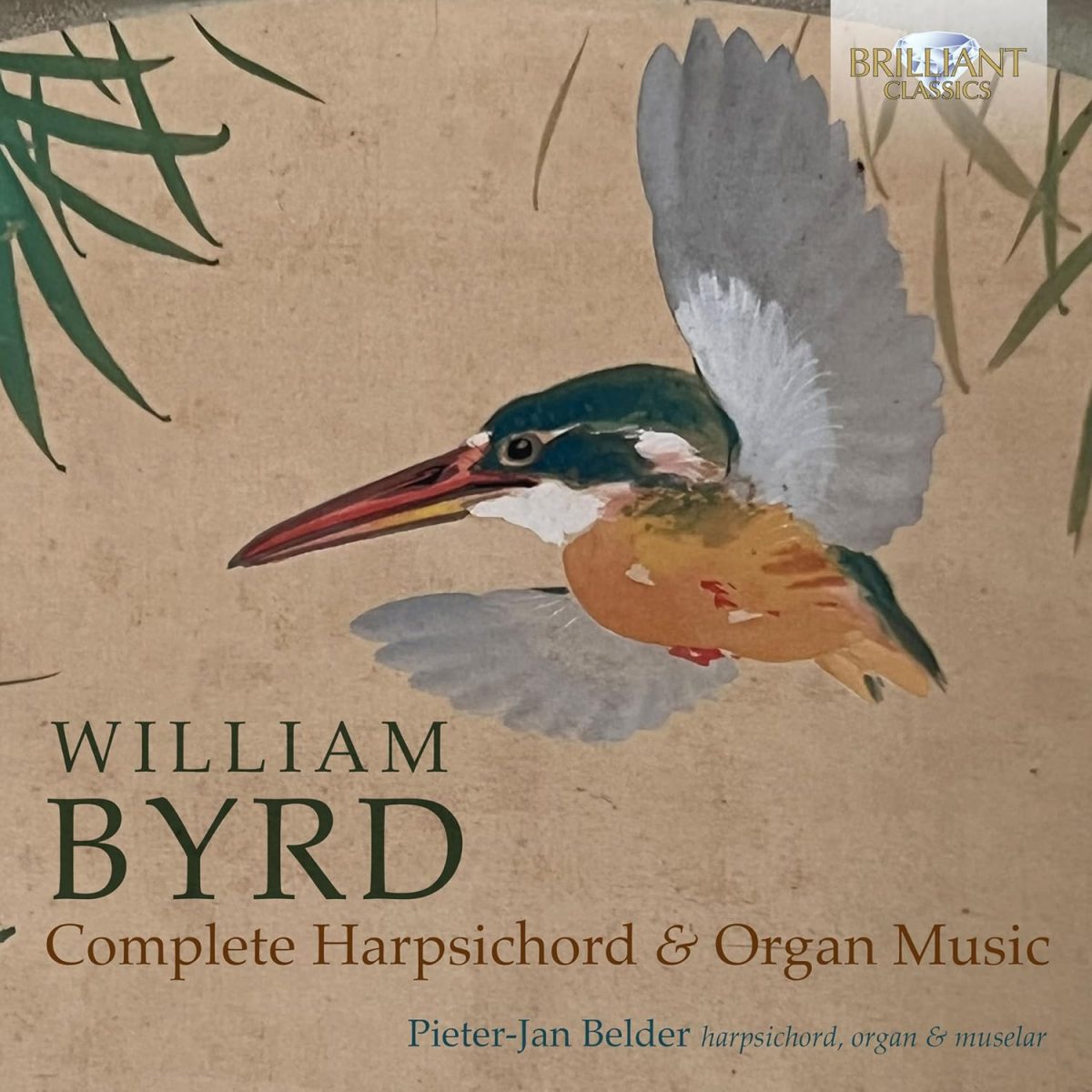

Pieter-Jan Belder harpsichord, muselar, virginals and organ

9 CDs

Brilliant Classics 97074

This album of Byrd’s complete music for keyboard is in every way a worthy successor to Davitt Moroney’s pioneering boxed set released in 1999 (Hyperion 66551-7, reissued 2010 as CDS444617). Musically the fact of the music being by Byrd is self-recommending. He was the first great composer for the keyboard, writing music that is not only attractive on its own account, transcending the liturgical parameters of preceding repertory, but also idiomatic to the harpsichord, comfortable under the fingers as well as to the ears! As for performance, Belder’s strength is in allowing Byrd to speak through the music rather than inflicting an interpretative regime upon the music. The sheer variety among the pieces, well over a hundred in total, is mind-boggling, and thanks to the clarity of Belder’s readings, lesser-known jewels such as the Pavan and Galliard BK 16 glow in their own light, while the neglected Pavan and Galliard BK 76-77 (probably intended as a pair but not presented as such in their unique source) positively bask in the glow of Belder’s performance. More familiar masterpieces and classics such as The barley break, Walsingham, Ut re mi fa sol la (BK 64) plus the great sequence of Nevell pavans and galliards, the grounds and the fantasias (especially BK 13 in A minor, the first true masterpiece for the keyboard) flourish in this environment.

An interesting talking point, possibly controversial to some, is Belder’s choice of “fringe” repertory. Most of the accompanying booklet is written by Jon Baxendale, experienced co-editor (with Francis Knights) of such important sources as My Lady Nevells’ Book, Will Forster’s Virginal Book and the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, though parts of his text must be read with caution: Byrd is now known to have been born in 1540 or late 1539, not 1542/3 as stated; he was appointed to the Chapel Royal in 1572, not 1573; he moved to Stondon Massey in 1595, not 1594; and pace Mr Baxendale, the anonymous variations on Robin Hood are not attributed to Byrd by Will Forster anywhere at all in his Virginal Book (WFVB), the work’s unique source. In a brief but informative personal note in the booklet about the recording project, Belder is “up front” about some inclusions, and one of these is Robin Hood (previously performed by Bernhard Klapprott on his complete recording of Thomas Tomkins Keyboard Music MDG 607 0704-2 with circumstantial evidence for Tomkins’ authorship on p. 12 of the booklet; and subsequently recorded by Bertrand Cuiller on Mr Tomkins his Lessons of Worth, Mirare MIR137, as by “Thomas Tomkins?”) but Belder cites the less assertive comments of Baxendale and Knights in their edition of WFVB (p. 372) merely suggesting tentatively that it offers traces of Byrd’s style. Half a dozen of Byrd’s songs survive in contemporary arrangements for keyboard. Two had already been recorded: Lullaby and Susanna fair. None are thought to be by Byrd himself, but rather than record all or none of them, Belder has decided to include a couple that “work” for him as works for keyboard. One such is the album’s single premiere recording! This is the arrangement for keyboard of Care for thy soul from the Psalmes, sonets and songs published in 1588; the original song has already been recorded twice. The other is Susanna fair. He also includes two settings of Dowland’s If my complaints. BK 103 is attributed to Byrd in its source but rejected as being by him, while BK 118 is anonymous but accepted as likely to be by Byrd. Belder explains this in his note so listeners can agree or disagree with scholarly opinion, or simply just enjoy both settings! In the same generous spirit, those pieces attributed uniquely to Byrd in contemporary sources, but considered improbable or impossible to be by him, are also included. A few works receive two “versions” performed on different instruments, such as the arrangement of Robert Parsons’ In nomine on harpsichord and on organ.

It remains wholeheartedly to welcome and recommend this fine discographical achievement. Pieter-Jan has recorded the pieces from Nevell and Fitzwilliam before but, given the many extra works here which include some gems which are outstanding even by Byrd’s elevated standards, and at its reasonable price, this boxed set is worth the attention – and outlay – of everyone who is already aware of this music, or who is moved to discover it.

Richard Turbet