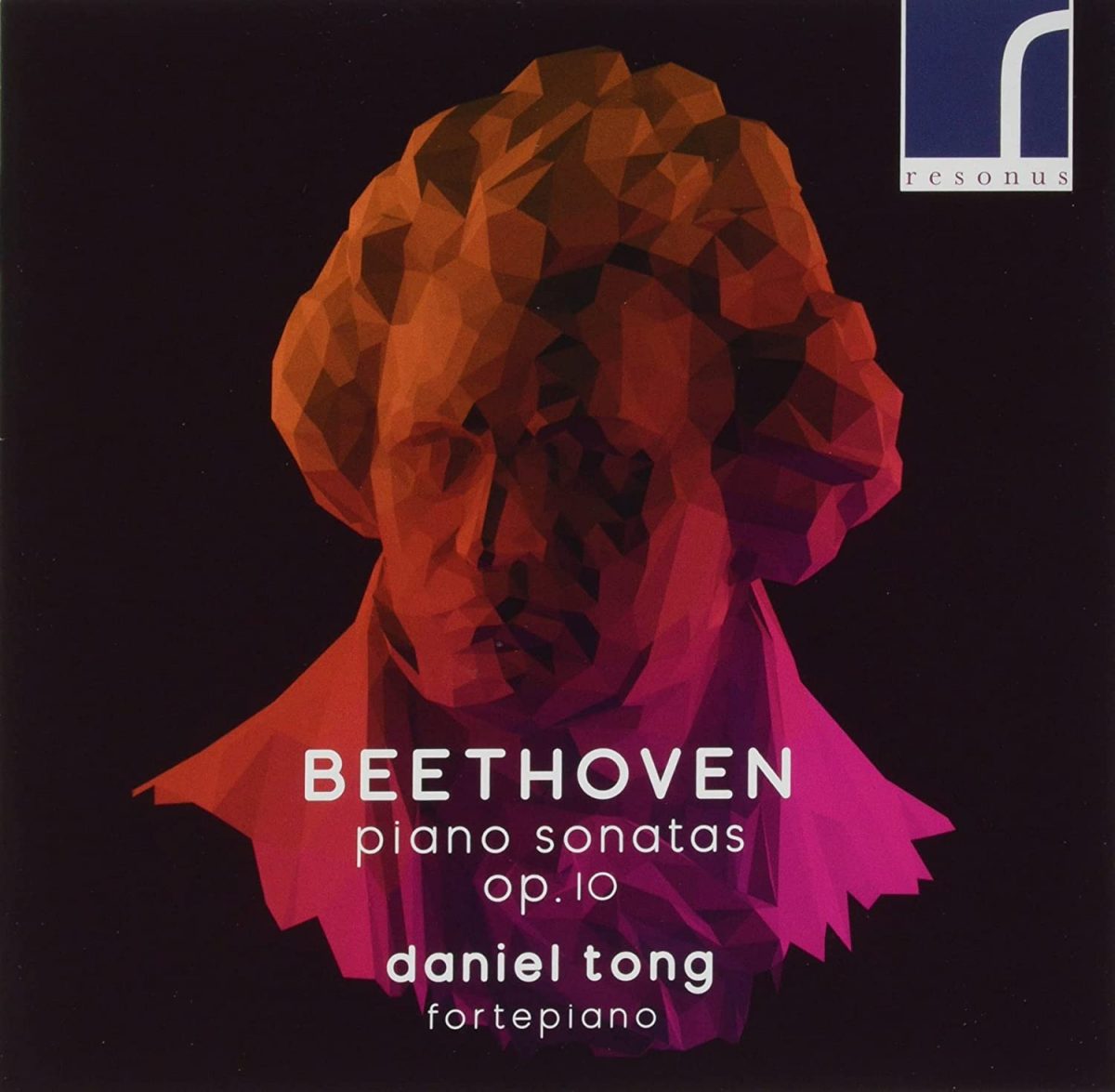

Daniel Tong

61:31

Resonus RES 10307

Daniel Tong here plays a copy of an Anton Walter fortepiano of 1805 built by the prolific Paul McNulty. In his informative note, Tong makes a number of points regarding the advantages of playing Beethoven on a fortepiano, correctly observing that it brings both the ‘player and the listener closer to Beethoven’s sound world’. Strangely, among other well-made points, he doesn’t mention what to me is always one of the principal advantages of playing the music of this period on a fine fortepiano, which this example unarguably is. That is the deliberate contrasts of tonal colour in the various registers of the instrument, one of the key differences to the modern grand piano, which aims for homogeneity across the spectrum. This seems to me particularly on display in the opus 10 sonatas, where one senses time and again that Beethoven is deliberately exploiting the contrasting sonorities of the instrument. This exploitation is especially potent in such imitative passages between treble and bass (much exploited in these sonatas) as the coda in the Presto of the D-major Sonata.

The three sonatas that constitute opus 10 were published in 1798 with a dedication to Countess von Browne-Camus, the wife of one of Beethoven’s wealthy patrons, one of several dedications of his publications to both count and countess. As Tong notes, the sonatas follow a pattern that applies to almost all of Beethoven’s publications in threes, aiming at works of considerable diversity and one work in a minor key (No 1 in C minor). The one thing all three have in common is their evident intent to provide above all music for Beethoven the virtuoso pianist who wowed the aristocratic salons of Vienna during the 1790s. This is particularly the case with the D-major Sonata, the only one of the three with four rather than three movements and at once the most ambitious and the most technically demanding for the pianist. Tong meets these demands admirably, articulating the virtuoso passagework of the Rondo finale with nimble fingers and great clarity. He is also capable of extracting poetry from the music where required, as for example in the final bars of the Largo e mesto of the same sonata, where the dynamics are exquisitely controlled to bring the movement to a close of perfectly attained peace. Neither is wit absent from Tong’s playing of a movement like the mostly playful Allegro of the F-major Sonata, where Beethoven uniquely in this set asks for the repeat of the development and recapitulation.

Overall these are admirable performances, enhanced by a recording that presents the instrument itself in the best light, its lovely bell-like treble admirably set off by a characterful middle register and richly resonant bass notes.

Brian Robins

One reply on “Beethoven: Piano Sonatas, op. 10”

“That is the deliberate contrasts of tonal colour in the various registers of the instrument, one of the key differences to the modern grand piano, which aims for homogeneity across the spectrum.”

I’ve been known to rant about this to people who seem to think Mozart played a Steinway. Looking forward to hearing this.