Archlute music from the Doni manuscript

Luca Tarantino

64:38

CGS 003

Click HERE to buy this download on amazon.co.uk

Archlute music from the Doni manuscript

Luca Tarantino

64:38

CGS 003

Click HERE to buy this download on amazon.co.uk

Pierre Gallon harpsichord

78:00

encelade ECL1901

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk as an mp3

This is a brilliant programme. There’s quite a preponderance of slow tempi so perhaps you have to be in the right mood to listen straight through but the music is all very good as are the performances (to say the least).

Charles Fleury de Blancrocher was one of mid-17th-century Paris’s leading lutenists, though nothing he did in his life (as far as we know) brought him anything like the fame generated by his death: he fell down the stairs in his house at the end of an evening spent strolling with Froberger. Tombeaux were composed in tribute for harpsichord by Froberger (of course) and Louis Couperin and – less widely known – for lute by François Dufaut and Denis Gaultier (the Younger) and they, together with Blancrocher’s only surviving work, form the spine of Pierre Gallon’s recital. The lute music is played on the harpsichord in transcriptions either by D’Anglebert or by the player in a similar style with the exception of the Blancrocher which, appropriately, ends the disc and is, indeed, on the lute (Diego Salamanca).

Two harpsichords are used, tuned in a meantone temperament at A=411. The temperament lends itself to all the style brisé writing (perhaps that should be the other way round) in that we hear its character though the idiom ‘takes the edge off’ what would otherwise be some pretty pungent chords. The recording captures the sound of all three instruments faithfully. Through headphones, there are a few fingering noises from the lutenist though I did not find them intrusive.

The booklet essay (in French and English) is a little fanciful for my taste though not as bad as some. However, a few typos do suggest that someone could have done a better job. But everything else is top drawer: strongly recommended for both the programme and its execution.

David Hansell

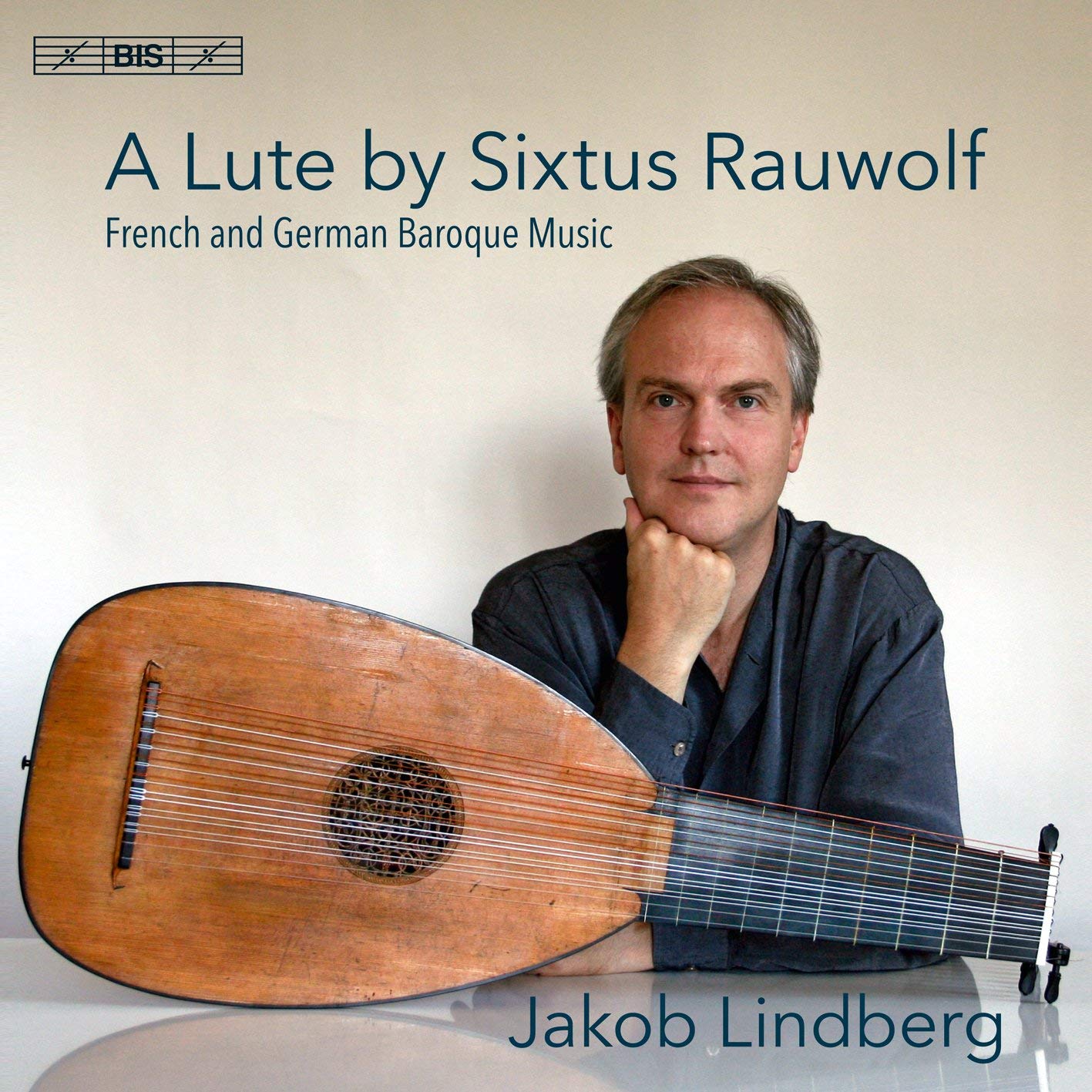

Jakob Lindberg

81:50

BIS-2265 SACD

Music by Dufault, Kellner, Mouton, “Mr Pachelbel”, Reusner, Weiss

Jakob Lindberg’s first CD featuring the lute made c. 1590 by Sixtus Rauwolf, is an anthology of music by French and German composers. It begins with a sombre Padoana by Esias Reusner (1636-79), which lies low on the instrument and is reminiscent of English lute pavans such as those by Daniel Bacheler. There follow two suites by two of the most important French lutenist composers in the 17th century, François Dufault (before 1604-c.1672) and Charles Mouton (1626-after 1699). The clarity of the Rauwolf lute is heard to good effect in Mouton’s jolly Canaries ‘Le Mouton’, where a high treble exchanges musical ideas with a lower voice, supported by occasional notes in the bass, giving the impression that three instruments are being played.

Towards the end of the 17th century, lute music waned in France, but it continued to wax in Germany. Lindberg plays a suite by David Kellner (c.1670-1748), who for much of his life worked as an organist in Stockholm. The suite begins with Campanella (presto assai), presumably an imitation of bells, but nothing like the change-ringing of Fabian Stedman and others which would have been heard in England by that time. The alternation of thumb and a finger creates a precise sound verging on the mechanical. Gone are the subtle suggestions of melody by earlier French composers. The old style brisé where melodies and bass lines were broken imaginatively into a succession of single notes, with Kellner they become more a predictable succession of broken chords, and if there is a slow-moving melody, each note is followed by an off-beat on a higher string creating a rather irritating drone-like effect. His Sarabande, on the other hand, has a charming melody, which is divided effectively into single notes for the double repeat. Interestingly, apart from cadential hemiolas, there are no notes stressed on the second beat of the bar, a feature which characterised earlier sarabandes; Kellner’s is more like a slow waltz. Next comes a suite by ‘Mr Pachelbel’, possibly Johann Pachelbel (c.1653-1706), best known today for having written a Canon. According to Tim Crawford’s liner notes, Pachelbel’s Allemande ‘L’Amant mal content’ is based on ‘L’Amant malheureux’ by the French lutenist Jacques de Gallot (d. c.1690). The CD ends with a fine suite in A major by Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687-1750), eight movements in all, including a Gigue played with tasteful panache, and a long Ciacona, with contrasting variations.

Stewart McCoy

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

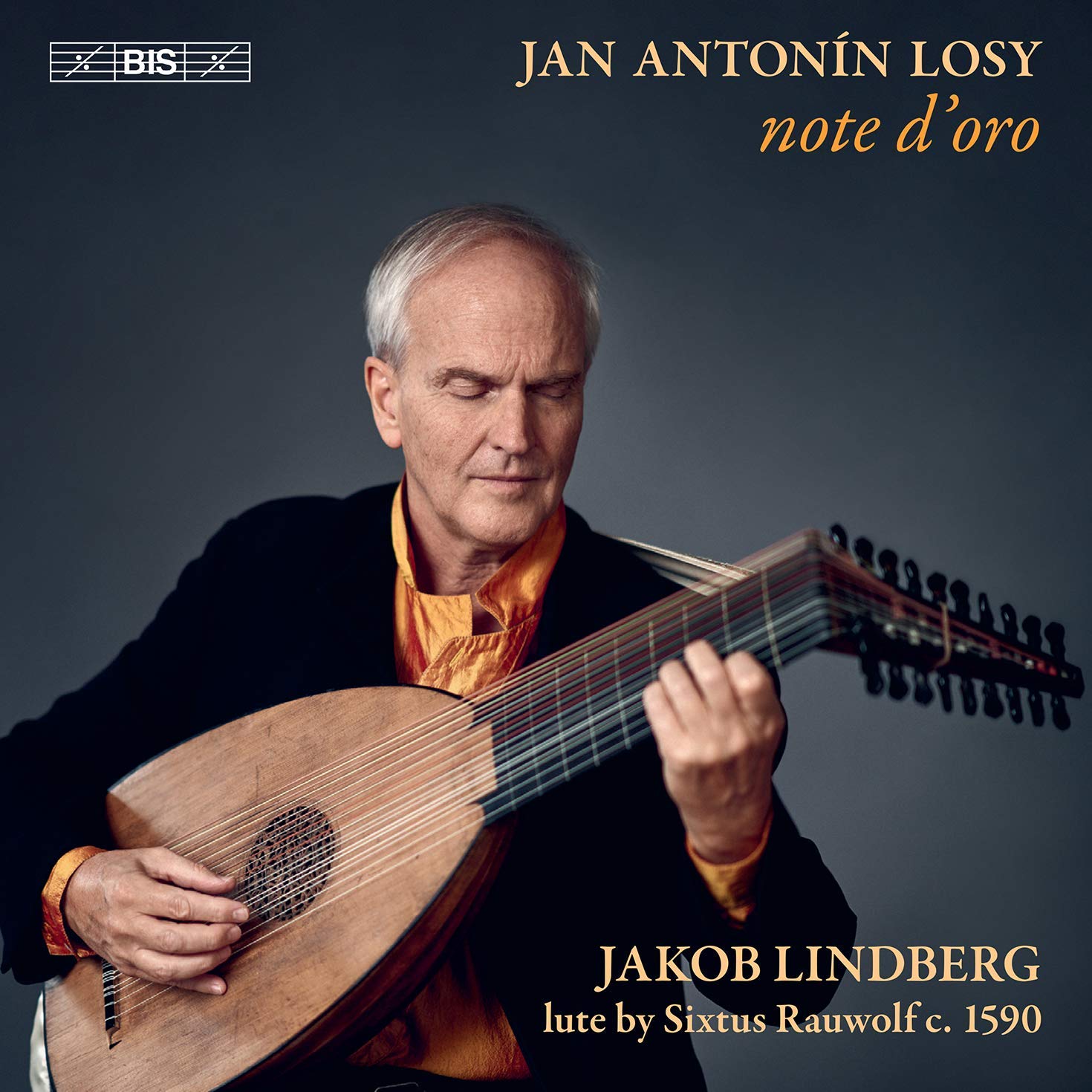

Jakob Lindberg

82:15

BIS-2462 SACD (ecopak)

Jan Antonín Losy (c.1650-1721) is arguably one of the most important composers for the 11-course lute, at least according to the frontispiece of LeSage de Richée’s Cabinet der Lauten (Breslau, 1695), where a pile of books has Losy’s music on top, above books by Gaultier, Mouton and Dufaut. I have always admired his music, and played some every day in 2019 without exception. His compositions are satisfying to play, pleasing to the ear, with well-sructured melodic lines, interesting harmonies, and considerable variety. There is a lightness of texture resulting from a fair amount of style brisé. In 1715, the Prague Kapellmeister, Gottfried Heinrich Stöltzel, described how Losy would savour a particular dissonance, calling it “una nota d’oro” (a golden note), hence the title of Jakob Lindberg’s CD.

The CD begins with a suite in A minor, compiled by Lindberg from various sources, including a Prelude adapted from one for baroque guitar, and a Courante and Double with an unobtrusive touch of notes inégales and a surprising secondary dominant towards the end. Lindberg’s playing is most gratifying – lively yet unhurried, with well-shaped phrases allowing the harmonies to follow their logical course to a final cadence, which is almost invariably decorated with dissonance on the tonic. An Aria is played at a very sedate speed, giving time for delicate ornaments to be heard clearly, followed by a thoughtful Gavotte enhanced by what I assume are Lindberg’s own additional notes for repeats. The suite ends with a lively two-voice Caprice, where fast running notes are shared between treble and bass. Next comes a suite in F major, the seven selected movements long known to modern lute players from Emil Vogel’s Z Loutnových Tabulatur Českého Baroka (Prague: Editio Supraphon, 1977). After a slow, stately start, the overture breaks into three fast beats in a bar, developing a theme of three crotchets and four quavers, before returning briefly to the slower speed of the beginning. Then comes a restful Allemande with much imitation, nice little variants (presumably Lindberg’s own) for repeats, and a passage of parallel tenths played brisé for the repeat. The overall pitch then drops for a Courante, which canters along in continuous quavers in style brisé, so that in the second section there are only three places where more than one note is played at a time. The piece ends with a descending sequence, which Lindberg decorates for a petite reprise. In contrast the following Sarabande has a thicker texture, with many rolled chords. Its second section begins with a surprising chord of C minor, played on the lower reaches of the lute – its highest note (g) is on the fourth course. As with so many of these pieces, Lindberg tastefully adds myriad extra notes to enliven repeats.

There is just one place in the whole of this delightful CD where I think something is not quite right. In the Sarabande of the Suite in D minor, the F major chord at the start of bar 13 should really be in root position, but Lindberg plays it as a second inversion with the note c in the bass, and does the same for the repeat. I wonder if his edition has that note accidentally notated one line too low in the tablature.

With suites in A minor, F major, G major, D minor, G minor and B flat major, ending with a Chaconne in F major, there is much to enjoy. Apart from Lindberg’s masterful playing, there is one thing which makes it all rather special: his lute was built c. 1590 by Sixtus Rauwolf of Augsburg, probably as a seven- or eight-course instrument, and surprisingly it still has its original soundboard. It was later adapted to be an 11-course lute, and was restored a few years ago by Michael Lowe, Stephen Gottlieb and David Munro. Its sound is well balanced, with clear bright notes in the treble, and bass notes which are not too loud and do not sustain too long. With its variety of tone colours, it helps make the music sing, and must undoubtedly be an inspiration to play. Note d’oro indeed.

Stewart McCoy

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Joachim Held lute

59:00

hänssler classic CD HC19034

Click HERE to buy this CD on amazon.

63:52

naïve E 8940

Music by Byrd, Dowland, Holborne, Huwet & Johnson

[dropcap]“[/dropcap]Mad Dog” is one of four fanciful titles Hopkinson Smith has made up for lute pieces on the present CD which survive without a title. He is undoubtedly right to say that this will make some people angry, and others laugh, but he is only following in an old tradition where titles, as well as notes, are changed from one version to the next. Smith does not give specific source references, perhaps because he does not reproduce accurately one particular version of a piece. Instead, he makes his own version, adding or removing ornaments and divisions. His playing is very pleasant to the ear, always thoughtfully expressive, with a delicate, sensitive touch, enhanced by the clear, sweet, mellow sound of his 8-course lute in F built by Joel van Iennep.

The first track, “Johnson’s Jewell”, is taken from folio 21r of Dd.2.11, which is the only source which has that title and written-out divisions for repeats. In making his own interpretation, he rakes back a 6-note chord (bars 4, 20, 24), removes an ornament (bars 11, 16, 32), adds an ornament (bars 34, 35, 42, 43), inserts high notes (bar 18), an extra scale up (bar 26) and down (bar 28), slows right down (bar 32), puts in a run of quavers (bar 40), adds fast off-beat quavers (bars 44, 45), changes a downward scale to an upward one (bar 49), and finishes with a petite reprise of the first eight bars.

Also by John Johnson is the Pavan to Delight. From his liner notes, Smith seems unaware that in 1580 the Earl of Leicester’s company of actors staged a play called Delight. The play is now lost, but it is possible that Johnson’s pavan featured in the entertainment. (I am grateful to Ian Harwood for telling me this.) It is certainly a fine piece of music, given a new twist here with Smith’s own florid semiquaver divisions. “Ward’s repose” is the title Smith gives to an untitled pavan by Johnson on folio 44v of Dd.2.11, in honour of his erstwhile tutor and friend, John Ward; it is in the unusual key of F minor, with typical Johnson figurations, and very beautiful.

Anthony Holborne’s “As it fell on a holly eve” and “Heigh ho holiday” [puns on Holborne’s name?] are played very quickly, but (for my taste) with a superfluity of rolled chords.

“Day’s End Pavan” is the title Smith gives to the pavan on folio 46r of Dd.2.11. With music of this quality, one can understand why Johnson was appointed lutenist to Queen Elizabeth. Unhurried, Smith sustains it well with some extra decorative touches of his own.

The “Mad Dog” is Anthony Holborne’s untitled piece on folio 45r of Dd.5.78.3 (no. 49 in the Lute Society’s Holborne edition edited by Rainer aus dem Spring). I am inclined to agree with Smith that the piece is more likely to be an air than a galliard. It hops along nicely as it shifts from 3/2 to 6/4. I think Smith’s speed is a little too fast, if only because he doesn’t always catch the quavers cleanly in bars 21 and 23.

There is much variety, including a fantasy by Holborne, a restful Pavana Bray by William Byrd, and a charming Shoemaker’s Wife by John Dowland. Smith attributes Gregorio Huwet’s Fantasy in Varietie at least in part to Dowland, although there is no evidence for this. Smith’s alteration to the harmony in bar 19 and 43 is convincing, but I don’t understand why he omits bars 28-34. Smith maintains the theme in diminution at bar 35 as in the source, but it is possible that a minim rhythm sign was omitted here (as suggested to me by Martin Shepherd), which would have maintained the theme in minims. At bar 55 Smith deviates from the original – he writes, “I have taken some liberty with the Fantasy’s structure” – adding notes of his own and repeating some bars, but I don’t see the need for this. The piece was fine as it was. Smith’s expansion of Mr Dowland’s Midnight, on the other hand, works extremely well, and turns a 16-bar miniature into something pleasantly more substantial.

The CD ends with the untitled piece on folio 28r of Dd.5.78.3, which Smith names “Fare thee well”. Its overall mood is surprisingly melancholic, so Smith chooses not to bring out its distinctive galliard rhythm, treats it as an end-of-the-day air, adds his own divisions for repeats, slows the pace by rolling many of the chords, and, with a petite reprise of the last four bars, lays this thoroughly satisfying CD to rest.

Stewart McCoy

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=GB&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=infocentral-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=GB&placement=B071D538YX&asins=B071D538YX&linkId=2f0caafc83a39b510aab03eb6d6b205c&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=DE&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=DE&placement=B071D538YX&asins=B071D538YX&linkId=3decc3ebb120983dbc3326f38c920e1b&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=B071D538YX&asins=B071D538YX&linkId=10b6866afc8cefd0ede20183165543d1&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

This site can only survive if users click through the links and buy the products reviewed.

We receive no advertising income or any other sort of financial support.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

Michele Carreca renaissance lute

52:43

deutsche harmonia mundi 88985374332

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]iacomo Gorzanis (c. 1525-1574) was a blind lute player from Puglia, who spent much of his life in Trieste. He is best remembered today for having composed twelve settings of the passamezzo antico and passamezzo moderno, each followed by a saltarello, in all 24 possible keys, although none of these is included in the present CD. Apart from Michele Carreca’s own tasteful setting for solo lute of “Marta gentile”, from Gorzanis’ Il Secondo Libro delle Napolitane a Tre Voci (Venice, 1571), all the pieces are taken from Gorzanis’ four books of solo lute music published between 1561 and 1579. (Facsimiles of the original tablature may be found on line via the ever-useful http://www.jobringmann.de/facsimile-links.) According to the CD booklet, 16 of the 25 tracks are world première recordings.

Michele Carreca plays all six fantasias from the Libro Quarto. They consist of imitative polyphony mostly in four parts, with various contrasting ideas. In Fantasia Prima there are four bars with a distinctive “dum diddy” rhythm, soon followed by a couple of bars with quavers working their way from the lowest note G up two octaves and a fourth to c”. It is not always technically possible to sustain some bass notes while there are treble divisions, for example in bar 29, but Carreca does well to disguise this with fluent, forward-moving playing. Surprisingly he omits four perfectly playable notes in bar 5. Did he accidently miss them out when copying out the music? A feature of Fantasia Seconda is the frequent use of five- and six-note chords. Carreca spreads them at varying speeds for the sake of expression, resulting in a freer overall rhythmic interpretation. Rhythmic freedom is less desirable, however, in Fantasia Terza, and I feel Carreca could have taken his time to make it more steady. He omits notes at the beginning of bars 15 and 17. The theme of Fantasia Quinta is coincidently the same as the first eight notes of the well-known hymn, “All creatures of our God and King” (sung to the tune “Lasst uns erfreuen” from the Geistliche Kirchengesang of 1623). After all four voices have entered imitatively with the theme, there are passages where the treble and alto are echoed by the tenor and bass, where running quavers are shared by the treble and tenor, and towards the end, where block chords are each played twice. There is much variety, nothing outrageous, just a mood of cheerful optimism in the key of F major. Carreca plays with a bright, clear tone, pausing for breath at cadential points, and rolling chords which he thinks require special attention.

Some of the dance movements are thematically related, for example, Pas’e mezo detto l’orsa core per el mondo, is followed by a lively three-time Padoana del ditto and a super-fast Saltarello del detto. I particularly enjoyed Pass’e mezo della bataglia which Carreca plays with a good, lively tempo and scintillating semiquavers at cadences. Gorzanis adds excitement to the echoing bugle calls with notes séparées followed by a sequence of um-chings leading to the final cadence, which Carreca plays with panache. (For anyone looking for the music, the three battle pieces are from Il Terzo Libro, not Libro Quarto as given in the liner notes.) With a few more lively dances including a nicely paced Saltarello detto il Zorzi, a couple of fine ricercars from Il Terzo Libro, and an intabulation of Baldassarre Donato’s “Occhi lucenti”, this CD gives us an idea why Gorzanis found favour with his patrons in Trieste.

Stewart McCoy

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=GB&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=infocentral-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=GB&placement=B01L32LWZ0&asins=B01L32LWZ0&linkId=e7d5bb1c520a1d6bcf25c719f75613b4&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=DE&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=DE&placement=B01L32LWZ0&asins=B01L32LWZ0&linkId=9dd1cdae7de7b8bf56570655adab572b&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=B07BZJV491&asins=B07BZJV491&linkId=b61384c17774f5897f68024b73cc87b6&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

This site can only survive if users click through the links and buy the products reviewed.

We receive no advertising income or any other sort of financial support.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

Jakob Lindberg

81:11

BIS-2202 SACD

Music by Marco dall’Aquila, Alberto da Mantova & Francesco da Milano

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he three Italian virtuosi represented here are Francesco da Milano (1497-1543), Marco dall’ Aquila (c.1480-after 1538), and Alberto da Mantova (c.1500-51), who was also known in France as Albert de Rippe. The CD begins with Francesco’s well-known Fantasia “La Compagna”, played by Jakob Lindberg at quite a fast tempo, with crystal clear notes in the treble supported by the distinctive timbre of gut strings strung in octaves in the bass. The sound of the so-called ‘Pistoy’ bass strings made by Dan Larson soon fades away, but this is actually an advantage: modern synthetic bass strings can ring on too long, muddying melodic lines.‘La Compagna’ is typical Francesco: a polyphonic section develops the opening theme of d”, e” flat, d”, followed by a fast little scale rising from g’. After 49 bars the pace intensifies with those same musical ideas explored in a variety of ways, culminating in a scale shooting up to the 12th fret. The same opening three-note motif recurs in Fantasias 66 and 33 (the fantasy to which Fantasia 34 is the companion). Lindberg’s tone quality is exquisite, but I wonder if the microphone was too sensitive or placed a little too close to him. Particularly in the slower pieces one can hear background squeaks produced by his fingers as they move along the strings, which would not be so noticeable in a live performance. This is evident, for example, in Ricercar 51, which he takes at a slower, more reflective speed (lasting 3’19”, compared with Paul O’Dette’s 2’41”). Other pieces by Francesco include Fantasias 3, 15, 22, 33, 55 and 66, and four intabulations of songs by Arcadelt, Festa, Richafort and Sermisy.

Unfortunately some lutenists today ignore Marco dall’ Aquila, erroneously seeing him as Francesco’s poor relation, yet they overlook some fine compositions, ranging from the short, simply stated Ricercar 30 to the more extended Ricercar 32. In his informative liner notes Lindberg describes Marco dall’ Aquila as an innovator, and draws attention to his use of broken chords in Ricercar 30, which is similar to the brisé style of lutenists 100 years later. Marco’s Saltarello ‘La Traditora’ bustles along nicely, with tasteful divisions now in the treble, now in the inner voice, adding momentum and uplift. His intabulation of Josquin’s Plus nulz regrets is a particularly fine piece of music, with unusual harmonies reminiscent of the 15th century.

The music of Alberto da Mantova is often very difficult to play, and his fantasias are generally quite long. Fantasia 20 is the longest track of the CD, lasting 6’51”. It consists of strict polyphony which occasionally produces some surprising dissonance. Lindberg’s unhurried performance is masterful, as he gently plays off the different voices against each other with carefully shaped phrases. Alberto’s five variations on La Romenesca ground have rather prosaic divisions, and the last is punctuated with predictable little dabs of fast cadential figures. His virtuosity is more evident in his intabulation of Festa’s O passi sparsi, the first of two settings in volume 3 of the CNRS collected works: crotchet and quaver divisions in the treble and bass, extravagant semiquaver flourishes ending with super-quick demisemiquavers, brief excursions into triple time, and false relations (f natural/f sharp, e flat and e natural) adding spice to the harmony.

Stewart McCoy

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=GB&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=infocentral-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=GB&placement=B01JNPL376&asins=B01JNPL376&linkId=1c15d98073d24bf5d8b38633be83886c&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-eu.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=DE&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-21&marketplace=amazon®ion=DE&placement=B01JNPL376&asins=B01JNPL376&linkId=4d47f3ef2f5885e6bf478bb2857f9818&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

[iframe style=”width:120px;height:240px;” marginwidth=”0″ marginheight=”0″ scrolling=”no” frameborder=”0″ src=”//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=earlymusicrev-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=B01JNPL376&asins=B01JNPL376&linkId=4e95c2abf6bf9fa2ea04edf95c27d53f&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true”]

This site can only survive if users click through the links and buy the products reviewed.

We receive no advertising income or any other sort of financial support.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.