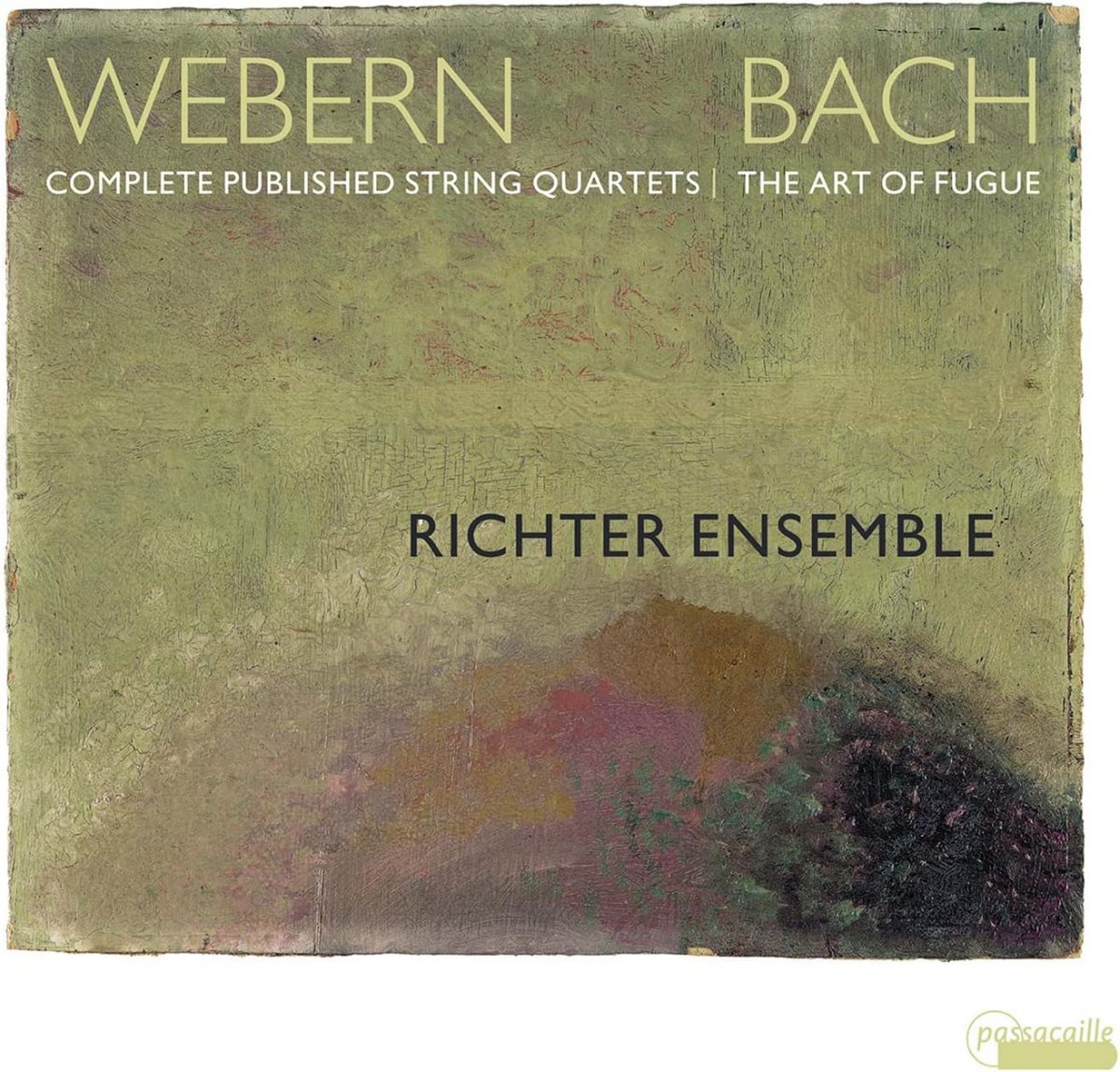

Complete published strings quartets | The Art of Fugue

Richter Ensemble

77:35

Passacaille PAS1129

This CD offers a novel approach, interspersing Bach’s Art of Fugue with Webern’s string quartet movements. ‘You find everything in Bach: the development of cyclic forms, the conquest of the realm of tonality – the attempt of a summation of the highest order’, said Webern, and both composers recorded here display the exploration of the logic that canonic and fugal writing imposes.

The Richter Ensemble are joined by Paolo Zuccheri (Violone) and James Johnstone (harpsichord) for the Bach, which they play at A=415Hz and recorded in France in 2019. The Webern is played at A=432Hz and was also recorded in France, but in 2021. The shift in pitch between the Bach and Webern is perceptible, but oddly, not disturbing to me; and the grouping of The Art of Fugue numbers into simple fugues (Contrapuncti I-IV), stretto fugues (Contrapuncti V-VII), double and triple fugues (Contrapuncti VIII-XI) and mirror fugues (Contrapuncti XII-XIII, and finally XIV at the end) allow for coherent groups of increasing complexity to mirror the chronological development of Webern’s Op. 5 (1909), the Six Bagatelles Op. 9 (1913) and the late Quartet Op. 28 (1937/8).

So not every possible piece from the later version of The Art of Fugue is included, and the liner notes make it clear that it is the juxtaposition of the very different composers that is at the heart of the CD’s purpose.

I found this refreshing, and illuminating – up to a point. I am no expert in Webern, and I do not have scores of much of his music. But the well-recorded dynamic range suggests that the players are masters of this highly nuanced music, and the effects produced in terms of glissandi, pizzicato and exceptionally well-tuned intervals. For the Bach, the ensemble grows in grip and power when joined by the violone and harpsichord.

An oblique observation: most of the performances of The Art of Fugue opt for the clarity of one-to-a-part scoring as must have been standard in viol consort playing (and singing) until the second quarter of the 18th century at least. While it is most likely that Bach – if he ever thought of a live performance of the material we know as The Art of Fugue – would have used a keyboard for preference, this performance quarrying material that reflects most nearly the intellectual and disciplined focus of the composer’s life and work and the transmission of that legacy to the 20th century certainly has its place in that towering edifice of polyphonic complexity.

David Stancliffe