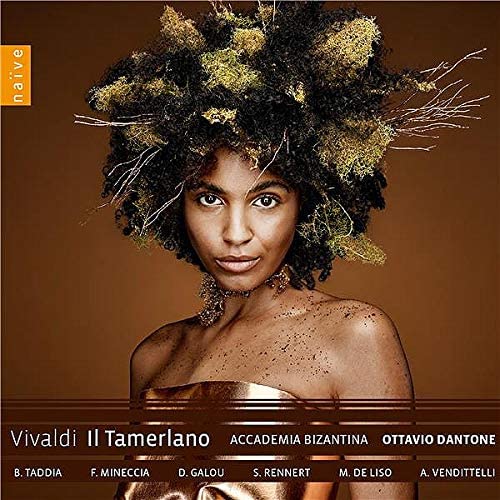

Bruno Taddia Bajazet, Filippo Mineccia Tamerlano, Delphine Galou Asteria, Sophie Ennert Irene, Marina De Liso Andronico, Arianna Vendittelli Idaspe, Accademia Bizantina, Ottavio Dantone

Vivaldi Edition vol. 65

155:00 (3 CDs in a box)

OP 7080

Click HERE to buy this recording on amazon.co.uk

Volume 65 of naïve’s remarkable Vivaldi integrale brings us one of the last of the complete opera’s still to be recorded. Il Tamerlano is one of Vivaldi’s later operas composed not for Venice but the historic Accademia Filharmonica of Verona, whose appointment of Vivaldi as impresario for the 1735 Carnival season resulted in two operas, Adelaide and Il Tamerlano, both probably premiered in January.

Of the now lost Adelaide, we know nothing beyond the fact its libretto is most likely by Antonio Salvi (a text set by Handel as Lotario in 1729), while Il Tamerlano is a pasticcio assembled by Vivaldi from previously composed operas of his own and those of Giacomelli (3 arias), Hasse (3) and Riccardo Broschi, Farinelli’s brother, two of whose arias were incorporated. They are all identified in the booklet, though it’s quite fun to listen first and see how many one can identify as not being by Vivaldi. One of the most remarkable to my mind is ‘Sposa son disprezzata’ (As a bride I am despised), taken from Giacomelli’s Merope (Venice, 1734). It is an aria for Irene, the woman abandoned by her fiancée Tamerlano for Asteria, the daughter of the imprisoned Bajazet, who he has conquered in battle. Full of stabbing pain and dissonance, it serves as a reminder that Giacomelli still remains undeservedly neglected. Vivaldi was thus left with just the recitatives, including several accompagnati, to compose from the libretto by Agostino Piovene, a book first set by Gasparini as Il Bajazet in 1711 and subsequently by several others composers including Handel in 1724. The piecemeal nature of Il Tamerlano thus serves to remind present-day opera lovers that far from being a despised form it is often characterised as today, the 18th-century pasticcio was a valid form in itself, utilised by just about every major opera composer of the day, including of course Handel.

The reason it was possible to swap arias from one opera to another is because arias fall almost exclusively into one of two forms: generic expressions of human emotions such as love, hate, jealousy and so on, emotional expressions obviously as valid today as they were in the 18th century; or more impersonal so-called ‘simile’ arias that compared feelings or impressions with something in nature, like a storm at sea. Plot came a long way behind poetic expression and Il Bajazet is unusual in this period in having a strong, direct storyline that concerns the all-conquering Tamerlano’s relationships with the defeated, yet still proud and stubborn Sultan Bajazet and his daughter Asteria, the true heroes of the story (the original libretto was called Il Bajazet). Only with the death of Bajazet does Tamerlano renounce his philandering and turn to being the nobly forgiving and repentant ruler the sentiment of opera per dramma dictates he must finally be.

Ottavio Dantone and his Accademia Bizantina have for a while now been the performers of choice for the operas in the Vivaldi Edition (along with a number of orchestral issues). It is not difficult to see why. In 2019 they produced a superlative account of Il Giustino (1724), an issue matched by this Il Tamerlano, which might be described in a single word: electrifying. Rarely does a studio recording have the febrile excitement we encounter here, a performance in which Dantone has galvanized every one of his performers into singing or playing with an intensity that ranges from anger to distress, from tenderness to evocation of the gentleness of the turtledove. It is founded on Dantone’s belief in the sanctity of text, a belief that provides a foundation for all his opera performances and which involves extensive work on recitative. Virtually every word is invested with meaning and expressed by an outstanding cast that has bought totally into the approach. It would be difficult to envisage more convincing performances of Bajazet, originally a role for tenor, but here commandingly sung by the light baritone Bruno Taddia, of Asteria, a glowing, finely-nuanced assumption by Delphine Galou or the supremely accomplished Tamerlano of Filippo Mineccia, now surely well up near the top of the countertenor league in a crowded field. Of the remaining roles soprano Marina De Liso is a near-flawless Andronico, the Greek Prince who would save Bajazet and loves and is loved by Asteria. Arianna Vendittelli (Idaspe) and Sophie Rennert (Irene) complete a cast that matches Dantone’s fervent advocacy, though neither is free from the common failure of lack of vocal control above the stave. It remains only to note that ornaments are mostly fluently and stylishly added, though as usual cadential (and other) trills are largely noticeable by their absence. But we do get an even more rarely heard ornament from Vendittelli in the shape of a perfectly executed messa di voce in Idaspe’s opening aria.

It hardly needs saying in conclusion that Dantone’s Il Tamerlano is a magnificent achievement, unquestionably one of the most important issues of a wretched 2020 redeemed in part by some truly remarkable recordings.

Brian Robins