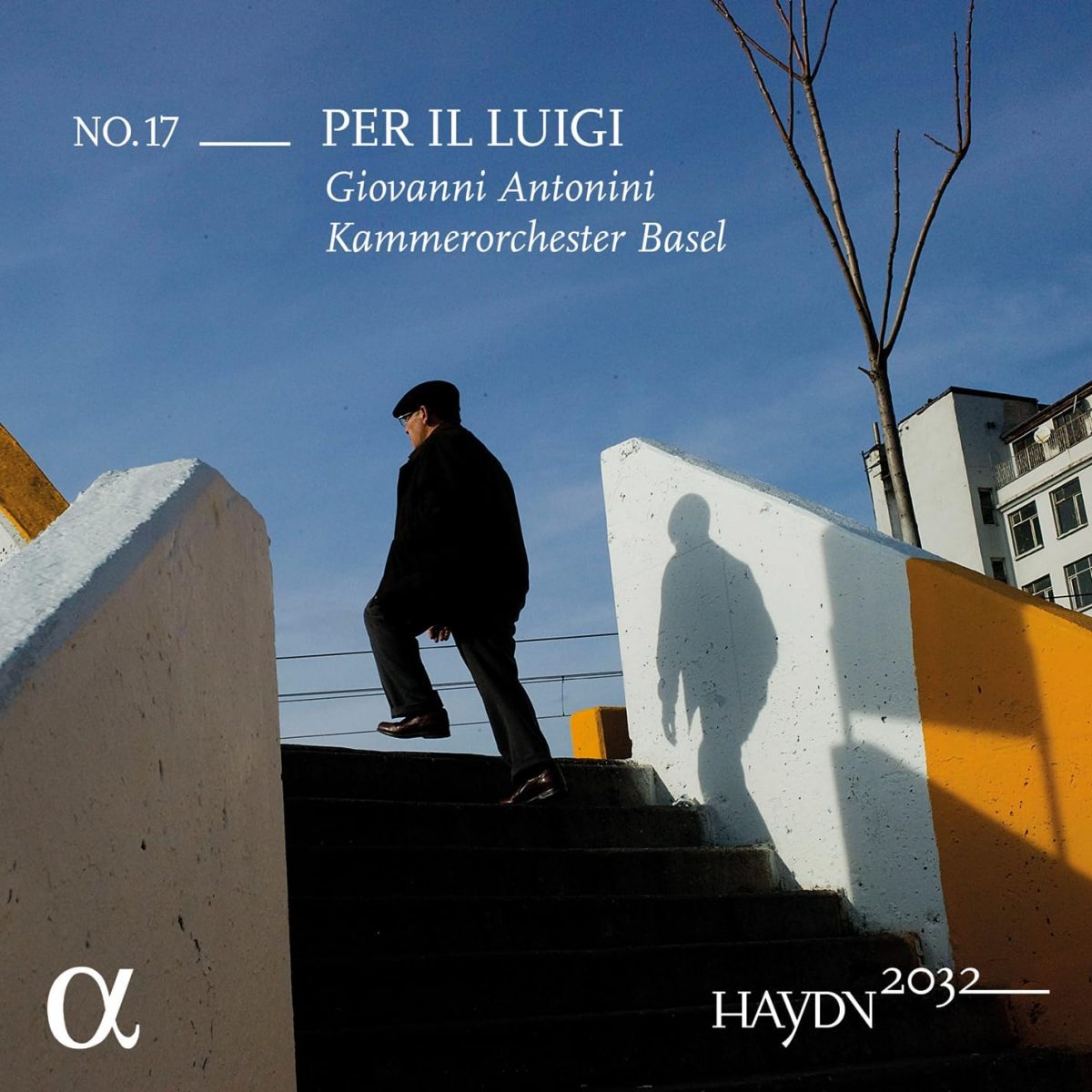

Dmitri Smirnov violin, Kammerorchester Basel, conducted by Giovanni Antonini

73:55

Alpha Classics 1146

The 17th in the splendid series of the complete Haydn symphonies directed by Giovanni Antonini features him directing one of the two orchestras he is working with (the other is of course his own Il Giardino Armonico) in three early symphonies from the 1760s. But as anyone familiar with the cycle will be aware, it is valuable not only for the symphonies, but also the tasty extras generally thrown into each selection. Here, the CD takes its name from the dedication Haydn wrote to the violinist Luigi Tomasini at the head of his Violin Concerto in C – ‘fatto per il luigi’ (composed for Luigi). Tomasini joined the Esterházy orchestra as leader in 1761, the same year as Haydn became vice-Kapellmeister, and the undated concerto probably belongs to much the same period. In his early years at Esterházy Haydn diplomatically composed many solos in his orchestral works to allow his players to make an impression, the most famous example of course being the ‘times of the day’, trilogy, Symphonies 6, 7 & 8.

Tomasini was something of a capture for Esterházy, an outstanding virtuoso capable of double-stopping with perfect intonation and the possessor of a beautiful, Italianate tone that allowed him to play long, cantabile lines with sustained purity. Both these assets are unsurprisingly fully exploited by Haydn, with double-stopping from the outset of the rather dignified opening Allegro moderato to the aria-like sustained sotto voce of the lovely central Adagio. The third movement is a delightfully bouncy Presto that calls for plenty of double-stopping and considerable agility from the soloist. These demands are met in exemplary fashion by Dimitri Smirnov, a semi-finalist in the 2024 Queen Elisabeth Competition (Brussels), whose unwaveringly sustained lines in the Adagio are particularly admirable. I did wonder if perhaps his cadenza in the opening movement was a little over-elaborate for a work of these proportions, but it’s a relatively minor point in the context of such outstanding playing.

Taken together, the three symphonies included, No 16 in B flat (c.1763), No 36 in E flat (c.1761-2) and No 13 in D (1763), provide a compelling explanation as to why so many music lovers regard Haydn with such affection. There are no masterpieces here, just good humour in spades, an abundance of spirit and energy, affectionately-shaped slower movements, and minuets that seem to belong as much to a country dance as they do to a court ballroom (No. 16 has in fact no minuet and only three movements). But, if not yet a masterpiece, there is one of these symphonies that does point toward the gradual emergence of a master. This is Symphony No 13, composed during a period when Haydn had four horns available at Esterházy. The composer took full advantage to open the symphony with strikingly rich sonorities – wind and horns over an urgent, driving string ostinato. The remainder of the symphony confirms it as something special among Haydn’s early works. The Adagio cantabile (ii) is one of those concertante movements in which the composer gave one of his outstanding instrumentalists a notable solo role, in the present case the cellist Joseph Weigl, who was also given a solo role in the central Andante of Symphony No 16. The final movement of No 13 has become famous for sharing the four-note Gregorian motif in the finale of Mozart’s Symphony No 41, ’Jupiter’, where it of course forms the basis for the extraordinary contrapuntal last movement. Haydn shows less inclination to treat it fugally – though there are hints – writing a movement equally divided between counterpoint and homophonic drive and energy.

The performances throughout attain the high standard that have become a feature of the series, being lithe, witty and pointed in quicker movements, while featuring playing always responsive to Antonini’s Italianate warmth in andantes and adagios. Just occasionally, as in previous issues, he gives cause to wonder if he gets lured into tempi that are a little too fast for the music, if not for his superb orchestras. Here, the final Allegro molto of the E flat Symphony is an example. But in truth the overall level of performance in this splendid series is making life increasingly difficult for the would-be critic!

Brian Robins