directed by Arnaldo Morelli

LIM Editrice [2021]

201 pp, €30

ISSN 1120-5741 recercare@libero.it www.lim.it

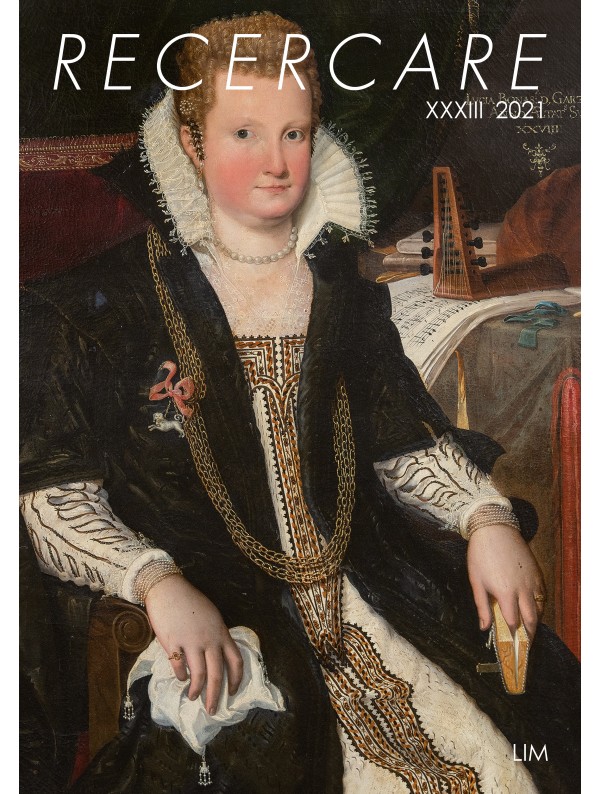

The 2021 RECERCARE contains four studies (two in Italian, one in French, and one in English), followed by, before the Summaries in Italian and English, a 21-page double Communication in Italian with 11 glossy colour plates concerning the 1590 portrait on the cover of this issue. In ‘La “gentildama” e liutista bolognese Lucia Garzoni in un ritratto di Lavinia Fontana’ Marco Tanzi correctly identifies the noblewoman of the portrait and gives convincing reasons for attributing it to Fontana. Dinko Fabris discusses the ‘Elementi musicali …’ it contains.

Lucia Bonasoni Garzoni (b. 1561-?) was an aristocratic Bolognese lute player praised in a sonnet and two madrigals for her beauty, talent and character. Four other portraits of aristocratic women known to be by Fontana (including another one of Lucia) and two paintings with groups of women are also shown and discussed, including a concert on Parnasso with Apollo playing the lira da braccio while Pegasus romps in the background, Lucia playing the recorder, and the other eight ‘muses’ on various instruments (including a lute like Lucia’s). Their instruments and the fashionable hairdo they share are slightly hard to make out on a small page, but a magnifying glass helps. Details in the five single portraits, on the other hand, are impressive. Fabris describes Lucia’s not quite contemporary 6-choir lute and the music underneath it: a thick, open manuscript book shows a third of a page with about 5 bars of a solo voice part in contemporary notation (four crotchets or two minims per bar) on pentagrams, aligned over the lute accompaniment in tablature on 6 lines. This combination, and the horizontal format, are said by Fabris to be rare, but it isn’t clear how else lute players could have accompanied, especially if they were also singing. There is no conjecture about an actual piece. Only four syllables are clear, which is unfortunate, and perhaps why guessing the two words involves fortuity or lack thereof: [pr-]ovida, [impr-]ovida, [a-]vida or [ar?-]ida + for[-tuna] or sor[-te]. A singer might recognize the fragment!

In ‘Polso e musica negli scritti di teoria musicale tra la fine del Quattrocento e la metà del Seicento’ Martino Zaltron presents some cross-disciplinary theories of the past about pulse and music theory, showing how ancient science and mathematics (in this case medicine and music) filtered down into Renaissance theory and on into the mid-17th century. He cites Tintoris, Gaffurio, Lanfranco, Aaron, Zarlino, Zacconi, Pisa, and Mersenne. Whatever familiarity readers may have with tactus and mensural proportions, and a personal sense of the relation between one’s pulse (and breath) to a piece of music, what is unexpected is the inversion of emphasis to the medical side of the relationship. Doctors Joseph Strus (1510-1569), Franz Joël (1508-1579), Samuel Hafenreffer (1587-1660) and polymath Athanasius Kircher ‘notated’ patterns of heartbeats, sometimes associated with age or voice registers (suggesting pitch and dynamics), by note-values, using mixed values to record them for diagnoses. Hafenreffer even used a 4-line staff to place the values (from crotchets to longs) in ascending, descending or undulating rows. They curiously resemble cardiograms, and hospital oscilloscope monitors showing the frequencies and intensities of heart and lung activity.

At a deeper level, this article will stimulate readers to think of music’s capacity to reflect transient physiological humours, feelings and states of mind and how what began as a rather primitive musical physical-medical relationship was refined by musical theorists and professors of medicine. Zaltron has centered his research on musical-historical-medical writings in the Middle Ages and Renaissance at the Conservatory of Vicenza, and the University of Padua, historically, after Bologna, the second in Italy at which medicine was taught, from the 13th century.

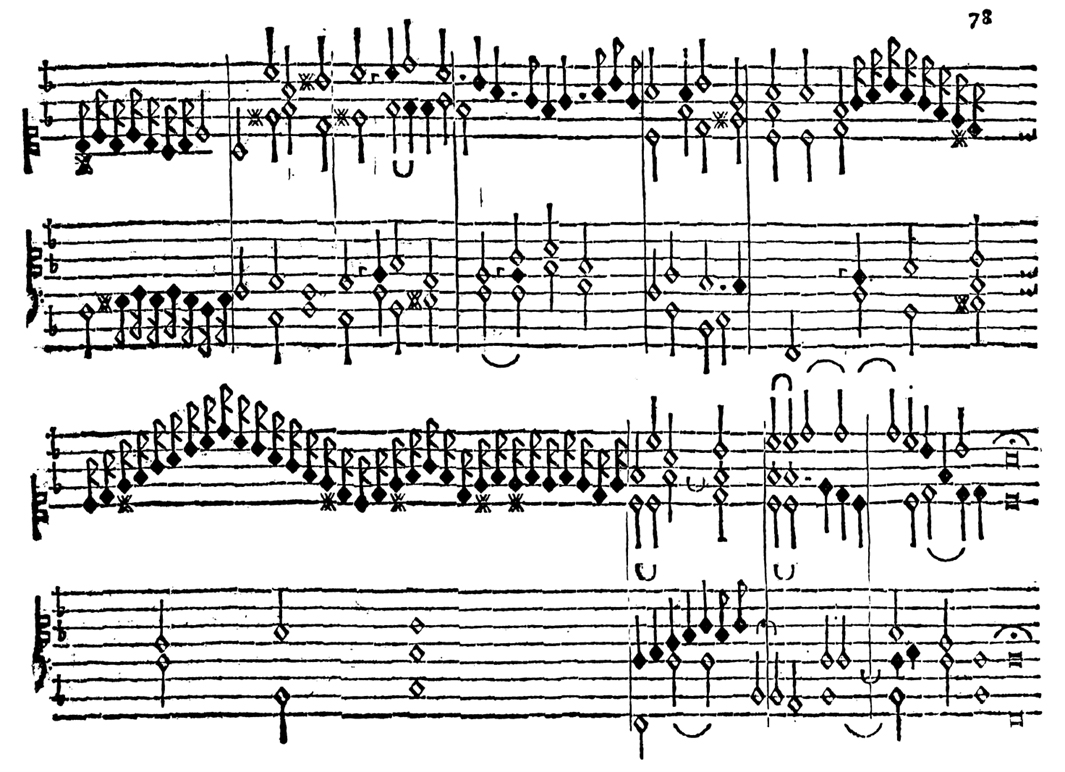

Adriano Giardina, in ‘Un catalogue pour improviser: les Ricercari d’intavolatura d’organo de Claudio Merulo’, concludes that the eight simple but long sectional ricercars of 1567 by Merulo (1533-1604), his first publication for organ, printed by Merulo in Italian keyboard tablature, were not primarily composed for performance, but rather for teaching aspiring organists how to extemporise contrapuntal ricercars, i.e. how to do so a mente and di fantasia – a skill required in church functions. Showing examples of the contrapuntal procedures used, accompanied by simple or parallel contrapuntal voices, he reasons that their purpose was didactic. Giardina also claims support for his thesis from Merulo’s younger contemporary Girolamo Diruta (1546-1624/25), who became his student (and A. Gabrieli’s) in 1574 at the age of at least 28, and transmitted their teachings and his own in a comprehensive treatise, Il Transilvano (1593 and Seconda Parte 1609), planned and completed over several decades, thanks to a long collaboration with Merulo, who endorsed the first part in 1592. Absent a preface to the 1567 Ricercari the thesis is possible but not provable, and implicit confirmation from Il Transilvano lacking.

So I have some reservations about what Giardina reads into Diruta. Ricercars and keyboard tablature do occupy significant portions of Il Transilvano, especially in the Seconda Parte, where Diruta covers modes and strict versus free counterpoint, in some ground-breaking detail, and advocates strongly for the use of Italian keyboard tablature (closed score notation) to facilitate the approximately correct and playable reduced arrangements of vocal and instrumental polyphonic music on keyboards. Tablature ensures the beginnings if not always the durations of essential notes, omits or transposes unreachable ones, notates very few rests because each hand usually has something to do, and respects the imitative counterpoint heard even where not clearly apparent on the page. It is far from ideal for illustrating how a ricercar is composed.

In fact, the 12 ricercars included in Book 2 of the Seconda Parte (pairs by Luzzaschi, Picchi, Banchieri, Fattorini and four by Diruta himself) are all in open score. They are there to be played and are thereby didactic for players who are learning to compose. Whereas with mosaic type in tablature Merulo can stack but not stagger three simultaneous notes on a staff, with only two possible stem directions. Space dictates which way very short or missing stems on inner voice notes point – perhaps why Merulo avoids voice crossings in these ricercars. The voices can be discerned in this tablature, after some scrutiny if not quite at first sight:

Being his own publisher, Merulo must have aimed to sell his music for organ both to professionals seeking handy modal material in excerptible sections, and to learners not yet up to composing ricercars, let alone improvising them. By playing them eventually by heart, their hands and ears might also acquire familiarity with the contrapuntal techniques. To that extent every composition played is somewhat propaedeutic to extemporization. Tablature slightly confounds this from occurring as less experienced players would have had to do the analysis that Giardina did in order to catalogue the techniques Merulo used.

While Diruta gives clear rules for strict and common counterpoint, and on how to compose and transpose within the modes, he never tells his Transylvanian pupil to improvise. Learning to play a mente or di fantasia does not exclude doing so next to pen and paper or an erasable slate, and those ambiguous terms are found only a couple of times in Il Transilvano. Their primary meanings are to play a mente, by heart; and to play or compose di fantasia, inventing rather than adopting a known composition as the basis for a new one. Memorization and invention are prerequisite skills for successful improvisation, but first of all for learning to compose, which comes first.

In fact, Giardina also mentions Diruta’s inclusion of 46 of Gabriele Fattorini’s 320 examples of elaborate ‘cadences’ in 4-part open score. He tells the Transylvanian to memorize them and to play them in transposition – and they are not mere chord progressions, but contrapuntal phrases up to 14 semibreves in length, with mixed note-values from semibreves down to quavers. A repertory of these ‘cadences’ in the hands and mind might well pass for improvisations. Tablature was still controversial and rejected by musicians in 1593 and 1609. If Merulo’s purpose was didactic, why didn’t he publish them in open score so that players in 1567 would have understood them? Why didn’t Diruta even allude to improvisation in his treatise, compared to how strenuously he advocated for making keyboard notation easier to play from in tablature?

Yet, at the end of the first part of Diruta’s Dialogo with the young Transylvanian, there is his personal account of arriving in Venice on Easter of 1574 and hearing a public ‘duello’ between Merulo and A. Gabrieli on the two organs of St Mark’s: they ‘dueled throughout the 18 years they were St Mark’s 1st and 2nd organists, though we don’t know exactly how. Were they improvising imitative rebuttals to each other’s improvised subjects, or did these eminent composers practice for their duels together? Diruta, already a keyboard player in 1566 when 20 years old and at 28 needing to perfect his technique in order to compete for posts, was swept away by their virtuosity – whether technical, creative, or improvisatory – and immediately arranged to study with both of them.

Extemporisation was indeed required of organists. To learn from Merulo’s ricercars, one would have had to sort out the voices in each, as Giardina has done, to note its devices. Applying the same techniques di fantasia, i.e. to an original subject, might then be within reach, especially when done al tavolino (at a table, i.e. in writing) rather than ex tempore. There is, in fact, a specific contemporary term for improvising counterpoint – contrappunto alla mente – and at least one organist, singer, composer and theorist, who dearly wanted to acquire that skill, gave personal testimony:

In the same year that Parte Seconda del Transilvano (1609) was reprinted (1622), Diruta’s contemporary, Ludovico Zacconi (1555-1627), in his Prattica di musica – Seconda Parte p. 84, writes: ‘… for however much, over time, I’ve frequented and conversed with masterful, mature and good musicians and seen how they teach their students counterpoint, I’ve never seen that [any] had a praise-worthy and easy way to teach their students contrappunto alla mente.’ Zacconi came to Venice to study counterpoint under A. Gabrieli, remaining active there from 1577 to 1585. He composed four books of canons and also some ricercars for organ. If as late as 1622 he claims that ‘no one’ can teach contrapuntal improvisation, which he sought to learn to no avail, hadn’t Gabrieli, Diruta, or Merulo himself recommended that he study the 1567 Ricercari, which he probably already knew? If so, sadly, they didn’t really help.

In ‘Dafne in alloro di Benedetto Ferrari: drammaturgia ‘alla veneziana’ per Ferdinando III (Vienna, 1652)’ Nicola Usula does three things: he compares the Modena and Viennese manuscript versions of Dafne, Ferrari’s first dramatic work (a vocal introduction in seven scenes to a pastoral ballet); he includes his complete critical edition of its text in the Appendix; and in the framework of Ferrari’s biography he shows how Ferrari used its Viennese production as clever marketing to secure his return to Italy. It might surprise us to think of Ferrari (1603/4 – 1681) not exclusively as a composer and lutenist, and perhaps also as a singer, but equally creatively as a poet.

He frames his study in a biographical account of Ferrari’s career, starting with his libretto for Manelli’s 1637 Andromeda, his collaboration with Monteverdi’s 1640 Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria and the music from his 1640 Pastor regio that became the end of Monteverdi’s 1643 Incoronazione di Poppea with Busenello’s text as ‘Pur ti miro’. As early as 1641 he dedicated his 3rd book of Musiche varie a voce sola to the Holy Royal Emperor Ferdinand III, and while active in Modena at the court of Francesco I d’Este (1644-51), and at the peak of his popularity, was hired as a theorboist to work in Vienna from November 1651. His Dafne was performed February 12, 1652 and he probably played in other Venetian-style musical dramas until March 1653.

Besides the Viennese manuscript (in the National Library), a manuscript copy is held in Modena in the Biblioteca Estense together with four other librettos. It is this later poetic version which Usula draws some interesting conclusions about. His critical edition inserts in boxes the previous readings where amended, and the quality of Ferrari’s revisions and how they affect the ballet are much to his artistic credit.

‘A newly discovered recorder sonata attributed to Vivaldi: considerations on authorship’ of Sonata per flauto, I-Vc Correr 127.46 in the Biblioteca del Museo Correr in Venice will interest recorder players, players of other instruments, and listeners, and not only for the discovery of this particular work. A Summary is not given for this meticulous study by Inês de Avena Braga and Claudio Ribeiro – perhaps because its first paragraph is in effect an introductory abstract, or because its thorough presentation of comparative musical details and the arguments against alternative uncertain attributions cannot be summarized. The gist is contained in its title, and the attribution is by the two authors. They point out the salient traits of Vivaldi’s compositional style over time, selecting from hundreds of direct self-quotes found between this sonata and specific Vivaldi works (39 sonatas, concertos, sacred works, operas from RV 1 to RV 820 being listed), with 25 musical examples filling 13 pages. They conscientiously consider how often other composers knowingly or probably not, also did so.

Therefore sifting through many sonatas by other composers showing similar traits might in the end be futile, with no end of passages ‘by’ Vivaldi and ‘also by’ others. They concluded their positive attribution after exercising profound insight into the creative logic typical only of Vivaldi but not of his copiers, in matters of style and structure, and after applying every other musicological and historical tool as well. Everyone will be enriched by their discussion because the musical traits are not only shown but explained in functional terms: how sequences, phrases, a harmonic juxtaposition, particular melodic moves or chords were used. The authors’ ‘contextualization’ strikes right to the matter of the authenticity of a work by Vivaldi.

The study goes on, in a sort of postscript, to name a few specific composers who warranted consideration as composers of I-Vc Correr 127.46 , as their music was so clearly influenced by Vivaldi’s: Diogenio Bigaglia, Gaetano Meneghetti, Ignazio Sieber, Giovanni Porta. This, too, provides the readers with a fresh discussion of their musical styles with respect to Vivaldi’s, despite superficial borrowings. It is rare that musical analysis is so rewarding to read.

Barbara Sachs