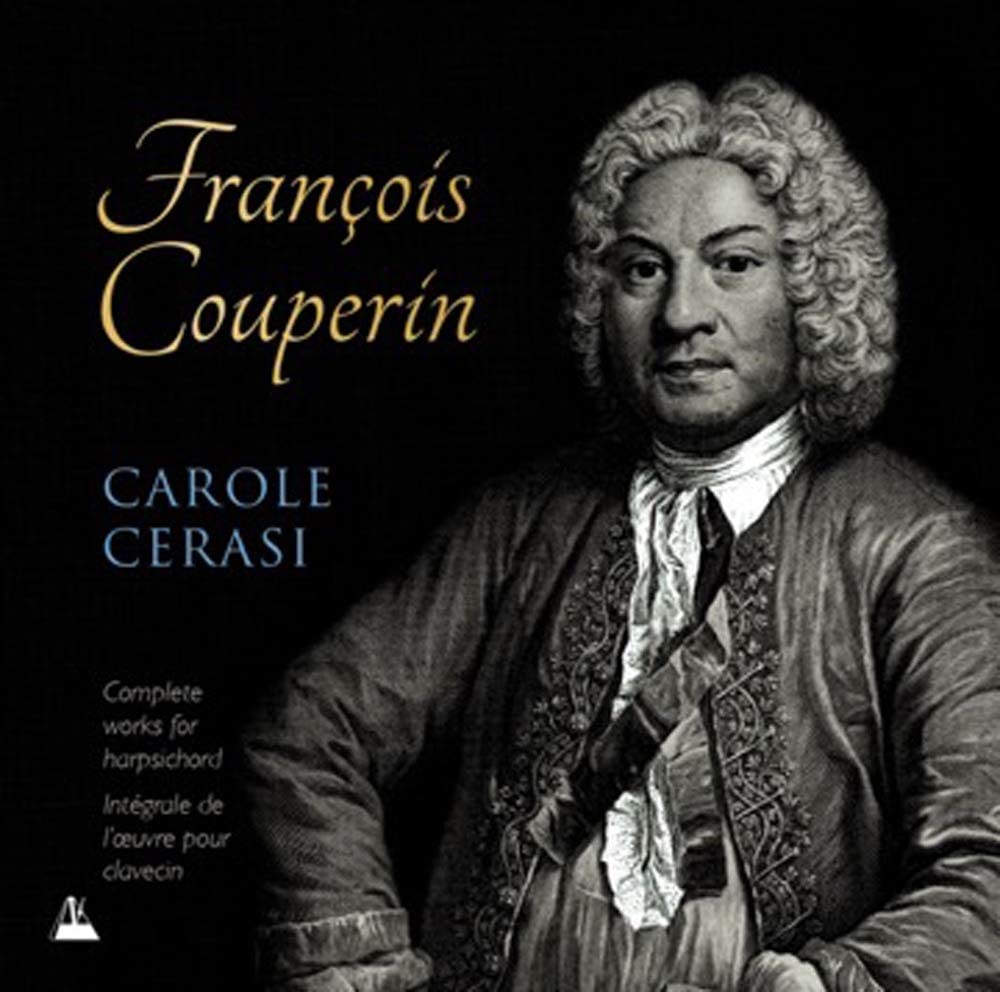

Carole Cerasi with James Johnstone harpsichord & Reiko Ichise gamba

Metronome METCD 1100 (10 CDs in a box)

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

To record and release the whole of Couperin’s seminal Harpsichord oeuvre is an astonishing act of faith and dedication. The lock-down times give amateurs (in the French sense) the chance to get to grips with and reappraise this amazing corpus of music which more than any that I know gives us a feel for what makes French music of the late seventeenth century so very distinctive.

Apart from L’Art de Toucher le Clavecin (1716), Couperin’s pieces are arranged in twenty-seven Ordres, each grounded in a particular key, but avoiding the tight structure of the Bach suites, where the formal series of dances provide a recognised structure. With Couperin we are in a looser, more wayward structure of movements with a more programmatic feel: the fascinating titles given to some pieces reveal the background in a theatrical imagination where reality is miniaturised, life-changing experiences immortalised in particularity and the trivial glimpse turned into an epigrammatic memorial. While Les Langeurs-Tendres in the Sixième Ordre is a classic bit of descriptive mood music, no-one really knows to what Les Baricades Mistérieuses refers. La Triomphante that opens the Dixième Ordre could not rattle the sabres more, while Le Petit-Rien is just what it says – a few insouciant bars of delight, ending the Quatorzième Ordre, with its birdsong pieces and the softly jangling bell-like notes of Le Carillon de Cythère.

Some of the most evocative pieces are written in the resonant tenor range which is so characteristic of Couperin’s style, like Les Ondes that concludes the Cinquième Ordre. But what makes or mars any recording of Couperin’s music are two factors: first, the player’s familiarity with the keyboard style of the period, where ornaments and their languid execution as well as the conventions of notation are so important for whether the playing feels French and second, the choice of instrument(s). For those who would like to sample Cerasi’s skills and sensibilities, I suggest they turn to CD 9.7-11, where they will hear not only Le Point du jour, L’Anguille and the Menuets Croisès but also her skill and immaculate sense of timing in the halting, sliding Le Croc-en-jambe and the magician’s sleight of hand in Les Tours de Passe-passe. I was brought up on Kenneth Gilbert’s recordings of Couperin, made in the 1970s, and it is largely his editions of the Ordres that I still use. But Cerasi’s playing has a grace, a flexibility and a subtle freedom, devoid of tiresome and faddish mannerisms, that I admire greatly. Cerasi is ably partnered in those pieces requiring two clavecins by her producer in this outstanding enterprise, James Johnstone.

For the instruments, she chooses a series of harpsichords, beginning with the Ruckers of 1636 that underwent a makeover by Henri Hemsch of Paris in 1763 in the Cobbe Collection at Hatchlands and ending with a splendid Antoine Vater of 1738 that seems to live in a private house in Ireland – now there’s a ray of hope in a dark world! The instruments – including the modern ones by Philippe Humeau (1989) after Vater 1738 and Keith Hill (2010) after a Taskin of 1769 – are all suitably French sounding and are all pitched at 415. I haven’t wearied of the wonderful sounds she coaxes from each harpsichord – so different in the languorous slow movements and so bright and fiery at times in the rondeaux, even after listening to the 10 CDs several times, and I don’t think they could be bettered: they certainly sing out better than those used by Kenneth Gilbert in the 1970s. Each instrument is illustrated in the accompanying notes, although ideally I would have liked more information on a website if not in the booklet, particularly on the 1738 Vater from Ireland, which sounds quite wonderful. Nor is there information on the temperament used: the keys are delightfully differentiated – the Eb and C minor are particularly dark and velvety, so my guess is that it is a sixth or fifth comma meantone system. But I trust Cerasi’s scholarship and research to know what was likely in Paris in the first quarter of the 18th century.

The main content of the booklet is an excellent essay, 21 columns long, by Nicholas Anderson, in both English and French. It manages to set Couperin’s oeuvre in its historical, visual and theatrical context, alert us to some of the more recent scholarship and writing and give us a feel for the distinctive nature of each Ordre – no mean achievement in this highly condensed format.

Each CD has a card sleeve with the content and timings of each piece listed on the back, and I am amazed and delighted in equal measure that it has been possible to issue the whole of this project for under £45.00. I don’t expect ever to hear a more thoughtful and intense yet playful and elegant version of Couperin’s great works, and Carole Cerasi has us all in her debt. Buy it at once, even if you’ve never heard more than a handful of these works before. This is all pure gold, and I know no better introduction to the French style than this.

David Stancliffe