Journal for the study and practice of early music

directed by Arnaldo Morelli

LIM Editrice [2020]. 242 pp, €30

ISSN 1120-5741 recercare@libero.it; www.lim.it

The 2020 RECERCARE contains seven studies, four in English and three in Italian, all the fruit of investigative perseverance, on specific works, prints, sources, situations or occasions. The relevance of uncovered historical details intrinsic to the creation of the music itself makes each article such a rewarding read. The full documentation, often provided in appendices, has more than a supportive role: aside from the specific cases discussed, it may greatly serve other researchers. Recercare is therefore an exponential boon to musical research.

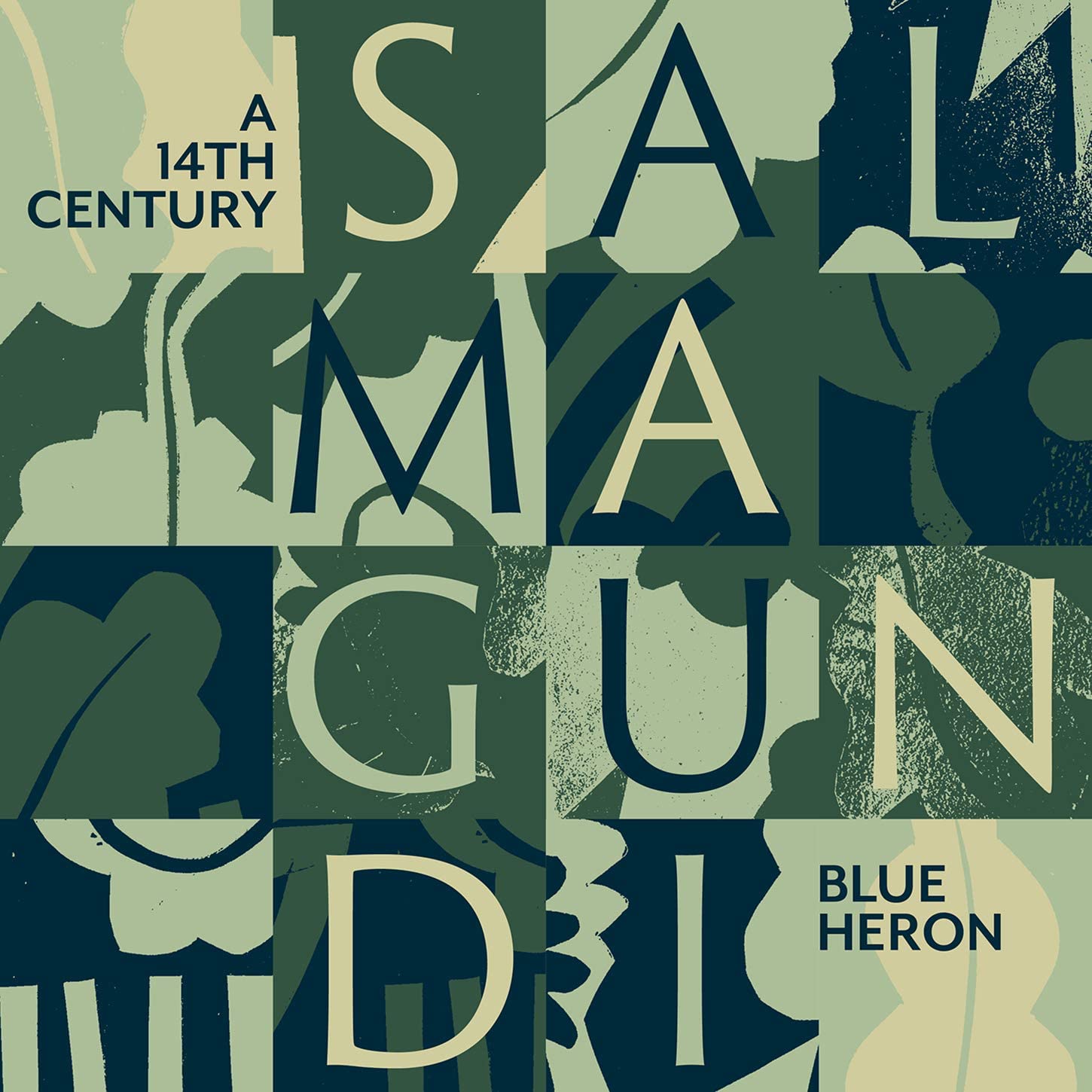

Elena Abramov-van Rijk asks‘ To whom did Francesco Landini address his madrigal Deh, dimmi tu’ [‘Say, tell me you … Who do you think you are!?’] While she describes the unusual musical and poetic structure of this ballata, which we have from various sources, it is its popularity and confrontational, accusatory tone that begs for a motive. The anonymous text could well be by Landini himself (Florence, 1325-1397), and the invective directed at a contemporary he knew or who was widely known, who accumulated valuable, portable riches in ‘easy’ ways. The author finds two potential candidates, both acclaimed court entertainers, whom she refers to (unfortunately, I think) as ‘buffoons’. In fact, both probably merited their riches, gained not-so-easily at all. The ballata itself does not refer to a performer, but every word seems applicable, and the careers of both are impressive: Dolcibene de’ Tori, crowned regem ystrionum in 1355 by the Roman Emperor Charles IV and invited to perform in many other courts, was an actor and ioculator (juggler), a poet (his poems ranging from the sacred to his problems with arthritis and impotence, sometimes with scurrilous vocabulary), a composer of canzonette, a singer, an organist and lutenist, and the protagonist of nine of Franco Sacchetti’s 300 anecdotal stories. Bindo di Cione, of Siena, the other, also served Charles IV and in other courts. It is the interpretation of Landini’s famous madrigal (of ca. 1355) that suggests so vividly how these talented entertainers thrived. The complete musical transcription follows.

Patrizio Barbieri ’s ‘Music printing and selling in Rome: new findings on Palestrina, Kerle and Guidotti, 1554–1574’ discusses four newly found disparate documents, presented as four pieces of an incomplete ‘mosaic’, and lastly, the inventory of a Roman bookseller and of a musician from Cambrai which included instruments, printed or handwritten vocal works, an iron music stand used while playing the harpsichords, and an erasable slate with staves for drafting music on. The description and purpose of the editions documented, and the contracts to publish and market them, show who covered the initial expenses, and whether any assistance was offered to authors or others. The publications discussed in detail are Palestrina’s Missarum liber primus (1554) and Kerle’s hymni totius anni et Magnificat (1558-60). The musical inventory of a general Roman bookseller, Antonio Maria Guidotti, includes a great number of almost exclusively Venetian prints of vocal music, mostly madrigals, plus treatises: B. Rossetti’s 1529 Libellus De Rudimentis Musices, G. M. Lanfranco’s 1533 Scintille di musica, and G. Zarlino’s 1558-2 Le Istitutioni harmoniche. The original documents in the Appendix may be useful to others for reflections and comparisons.

Franco Pavan’s ‘La musica per chitarrone di Giacomo Antonio Pfender. Nuove acquisizioni’ identifies Pfender, detto il Tedeschino, as the composer of some pieces for archlute in a manuscript in the Archivio Estense in Modena (and in a facsimile)1 previously attributed to an older composer, Alessandro Piccinini (1566-1638).

Pfender is known for having collected and published two states of Kapsberger’s Libro primo d’intavolatura di chitarrone in 1604 in Venice. They were close friends in their student days in Augsburg, and based on Kapsberger’s dates (1580-1651) they were in their early 20s in 1604. Pfender’s name reappears on designs for the frontispiece of another chitarrone collection, found in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de san Fernando in Madrid, where he is named as one of the composers. What the two collections share is a monogram resembling a stick figure with outstretched arms, turned-out feet, and a dot for the ‘head’. It actually consists of four superimposed letters, only two of which were previously noticed: an A and a swirl from its point to the middle of its right side form a P, thus suggesting Alessandro Piccinini. There are also short lines under the A’s two ‘feet’, a wide line balanced on its point, and a central dot above that line.

Pavan brilliantly deciphered the other two letters this monogram. The left side of A and the dot form a dotted capital I preceding AP, and the wide top line uses the right side of A to make a T. İAPT stands for Giacomo (Iacomo or Ioannes) Antonio Pfender, and T for Tedesco (German).

Many more useful considerations accompany this discovery: relations between Roman musical circles and Modena, the handwriting and probable date of the tablature, and a list of its 28 pieces: of which 7, not known from other sources, are attributed to ‘HK’ (Kapsberger), 9 to ‘AP’(?), 5 to ‘İAPT’ and several unattributed. Pavan modestly considers not quite resolved whether those identified as by ‘AP’ are attributable to Piccinini or to Pfender, but after keeping readers in legitimate doubt he adds that the abbreviations HK and AP appear to be in a different hand and ink! The facsimile of the Modena manuscript names only Kapsberger, Piccinini, and G. Viviani, and its editor, Francesca Torelli, was therefore forced to remark that the styles of HK and the older AP were surprisingly similar, so perhaps they were quoting each other! It is too bad that SPES (Archivum Musicum) no longer exists, because continuing this research and revising that introduction would be quite useful.

The Appendix gives Pfender’s letter of dedication of Kapsberger’s Libro primo d’intavolatura di chitarrone. He respectfully addressed Kapsberger as his fratello osservandissimo, and signed fratello amorevolissimo, ‘very loving brother’. It is a curious dedication, since Kapsberger had apparently not requested or given permission for publication. Pfender clears his conscience by saying that he published them in order to make Kapsberger a gift of what he stole, since up to then the pieces were so universally desired that they had become donnicciuole [derogatory term for little old women], whereas now he can peacefully recognize them and accept them back!

1 G. Kapsberger – A. Piccinini – G. Vivianai, Intavolatura di chitarrone. Mss. Modena, ed. facs., introduzione di Francesca Torelli, Firenze, SPES, 1999.

In March 2019 Maddalena Bonechi’s edition of G. B. da Gagliano’s Varie musiche, libro primo, 1623 was reviewed here. Her edition includes as much biographical information on Marco da Gagliano’s less famous brother Giovanni Battista (1594-1651) as there was to discuss. It also gave analyses of the works and their texts. Her present article, ‘Parole, immagini e musica nelle pratiche devozionali della compagnia di San Benedetto Bianco a Firenze – alcuni possibili contributi di da Gagliano’ focuses on the texts, imagery and music as essential to the devotional practices of the Florentine religious confraternity to which Giovanni Battista (and possibly Marco) belonged, and relates how paintings, poetry and music were fused in their spiritual activities. Whether or not the religious compositions in Gagliano’s publication were designed for the San Benedetto Bianco congregation, at least one was performed there: Ecco ch’io verso il sangue, presumably for a theatrical enactment of the passion and death of Jesus, along with the laments of Mary, traditionally for Good Friday. Depictions of the Passion and themes exalting God in comparison with one’s own nothingness and of penitence, enhanced the ritual flagellation practices of the members, who strived to gain insight from such first-hand experience. The beauty of the music and art may indeed have attenuated the rough physical sensory input incurred to stimulate and attain this understanding.

Lucas G. Harris – Robert L. Kendrick gave a curious title, ‘Of nuns fictitious and real: revisiting Philomela angelica (1688)’ to their fortuitous discovery and comparative analysis. A Benedictine nun, Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602 – ca.1677), had her 12 solo motets, Scherzi di sacra melodia, printed in score with a separate vocal part book in 1648 by Alessandro Vincenti. Only the vocal parts of this Venetian print survive. Forty years later Daniel Speer published a collection of Italian sacred works, his Philomela angelica, anagrammatically tagged “Res Plena Dei” [Daniel Speer], and attributed to ‘a Roman nun’. Speer’s print contains 24 motets, of which 6, with their continuo lines, are by Cozzolani, 3 by Cazzati, 1 duet attributed to the Ursuline nun Leonarda, and 14 not yet identifiable. What is fortunate is that in his search for Italian sacred pieces that would appeal to Lutherans in southwest Germany, Speer did have the continuo line.

By comparison of sources or by conjecture, Speer simplified the vocal writing, heavy ornamentation being out of fashion, deleted some Italian tempo or ‘mood’ indications, added string parts or sections, and slightly adapted the continuo figures to more Germanic usage. Harris and Kendrick are attempting to reconstruct Cozzolani’s originals, if they can distinguish her harmony and rhetoric from Speer’s arrangements. They have more to go by in the Cazzati and Leonarda pieces, which survive with their continuo parts.

Valerio Morucci examines part of the private correspondence of Christine of Sweden relating to her musical patronage and employment of singers, in ‘L’orbita musicale di Cristina di Svezia e la circolazione di cantanti nella seconda metà del Seicento’. Administrative documents, such as registers and accounts, have generally gone missing, but communications with singers and with other patrons, courts, cappellas, theaters, and cities (Rome, Venice, Mantua, Modena), await researchers who follow her lead. The degree of cooperation between other courts and hers, her granting of freedom to modify agreements in order for singers to accept additional work, and to establish goodwill between competing patrons, is surprising and admirable. Even this first exploration (the Appendix presents citations from 16 documents) regarding a small number of female singers and castratos will be of interest. They include: Nicola and Antonia Coresi, Barbara Riccioni, Giuseppe Maria Donati detto il Baviera, Giuseppe Fede, Alessandro Bifolchi, Giovanni Paolo Bonelli; other castratos such as Alessandro Cecconi, Giuseppe Bianchi, Antonio Rivani, and Domenico Cecchi detto il Cortona. Some were retained with salaries while many remained absolutely independent, such as Giovanni Francesco Grossi ‘detto Siface’ and Giuseppe Maria Segni ‘detto il Finalino’.

‘Writing a tenor’s voice: Cesare Grandi and the Siena production of Il Farnaspe (1750)’ by Colleen Reardon is a vividly engaging story. The details, gleaned from 119 letters to the inexperienced sponsoring impresario, Francesco Sansedoni, regard the ultimate success of a single opera, beset by numerous potential crises as originally planned, but methodically high-jacked by the ingenious, competent, hard-working, third tenor – and not only to further the careers of his second soprano wife and himself. Cesare Grandi offered and sufficiently motivated his unsolicited advice, eventually accepted by Sansedoni, reversing or manipulating almost every artistic and practical decision – major and minor changes affecting the music itself, the casting, the staging, the order of arias and their keys, the costumes, to suit the musical taste of the patron, and the local politics, or for practical reasons like not having the orchestral parts in the right keys after an aria was shifted from its original place in the libretto or even to be sung by a different singer. Famous as Siena was and is for its two summer Palios, tied to religious holidays, Grandi even obtained a change of its July date!

The recently discovered cache of letters containing Grandi’s psychologically astute suggestions to the younger Sansedoni would probably be bewildering to decipher and interpret without the help of Reardon’s orderly, detailed account. I don’t really have a pressing reason for rereading all 40 pages of this wonderful study (plus 15 pages with 29 appended letters), but it does bear more than one reading for the pure pleasure of pondering what a staggering pastiche an opera in 1750 was: the compromises, the pressures, deadlines met, singers cast, the copying, transposing, rewriting or replacing of arias by unnamed composers – thanks to the initiatives of the third tenor…

Barbara Sachs