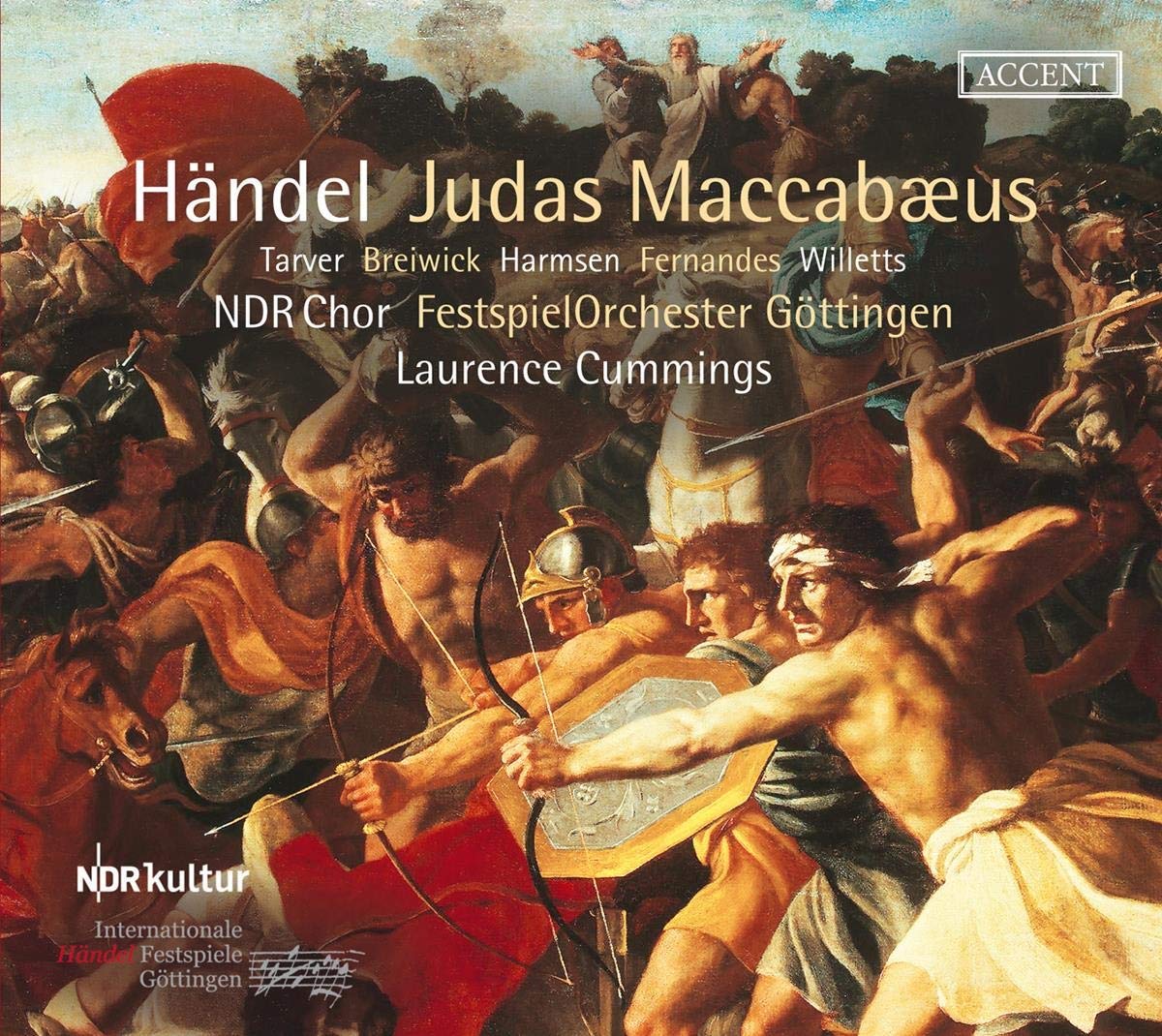

Tarver, Breiwick, Harmsen, Fernandes, Willetts, NDR Chor, FestspielOrchester Göttingen, Laurence Cummings

137:00 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Accent ACC 26410

Handel’s Judas Maccabæus, dating from 1747, was second only to Messiah in popularity in Handel’s lifetime. Here Laurence Cummings puts out a spirited version, recorded live last May at the Stadthalle Göttingen, where Cummings has been director of the Handel Festival since 2012. His orchestra, regularly assembled for this festival, is 6.6.4.4.2 strings with all the wind and brass you could need and sound not only proficient, but gracious. The string playing is particularly fine, and the occasional sounds of the wind – like the flutes in the final duet O lovely peace – offer lovely glimpses back to an earlier world before the ‘orchestra’ was essentially a string band.

The chorus, sharp and punchy when required but capable of a mellow and sustained gloom when called for, is the North German Radio Choir, their regular partners in this festival, and the text (and programme notes) are in both German and English.

Followers of the Festival’s productions will not be disappointed – the standards in every department are high. The main questions I have are about the size and scale of the performance.

Directors have to choose in presenting large-scale Handel – and even more so in Bach – between the stricter demands of period performance, which might call for voices especially of less developed power, and what will fill a venue and make the whole project financially viable. The solo singers here are admirable, but undoubtedly use more modern techniques of projection. They only rarely out-sing their accompanying band, and, of course, the oratorio is a heroic tale, but it was given first in the relatively small Theatre Royal in London.

The bass, Joäo Fernandes, is quite excellent in the very exposed The Lord worketh wonders, and Judas, Kenneth Tarver, is suitably heroic in Sound an alarm, where the silver trumpets eventually make their appearance to introduce the chorus, praising the abstract virtues of laws, religion and liberty, for much of the actual action takes place off stage making the work for all its political overtones in the wake of the Duke of Cumberland’s victory over the Stuart Pretender’s rebellion at Culloden so much more of an oratorio than an opera.

The opening of Act III marks Handel at his tuneful best in Father of Heav’n where the instrumental lines with their overlapping counterpoint suggest the all-encompassing divine favour. The March has cheerful bumpy jollity, and the unanimity of the chorus following, introduced by single voices, is a splendid advertisement for the about 21 strong NDR Chor, as is David Staff’s trumpet obligato in With honour let desert be crown’d, Judas’ surprisingly reflective final aria in A minor.

At the end of the brief final chorus, the burst of applause reminds us that this is a live take, and after such a seemingly effortless performance it is well deserved. Nothing is amiss, tempi are beautifully judged and if the scale of the performance calls for more modern vocal techniques than I would ideally have liked, then many people will enjoy this cracking good version.

David Stancliffe