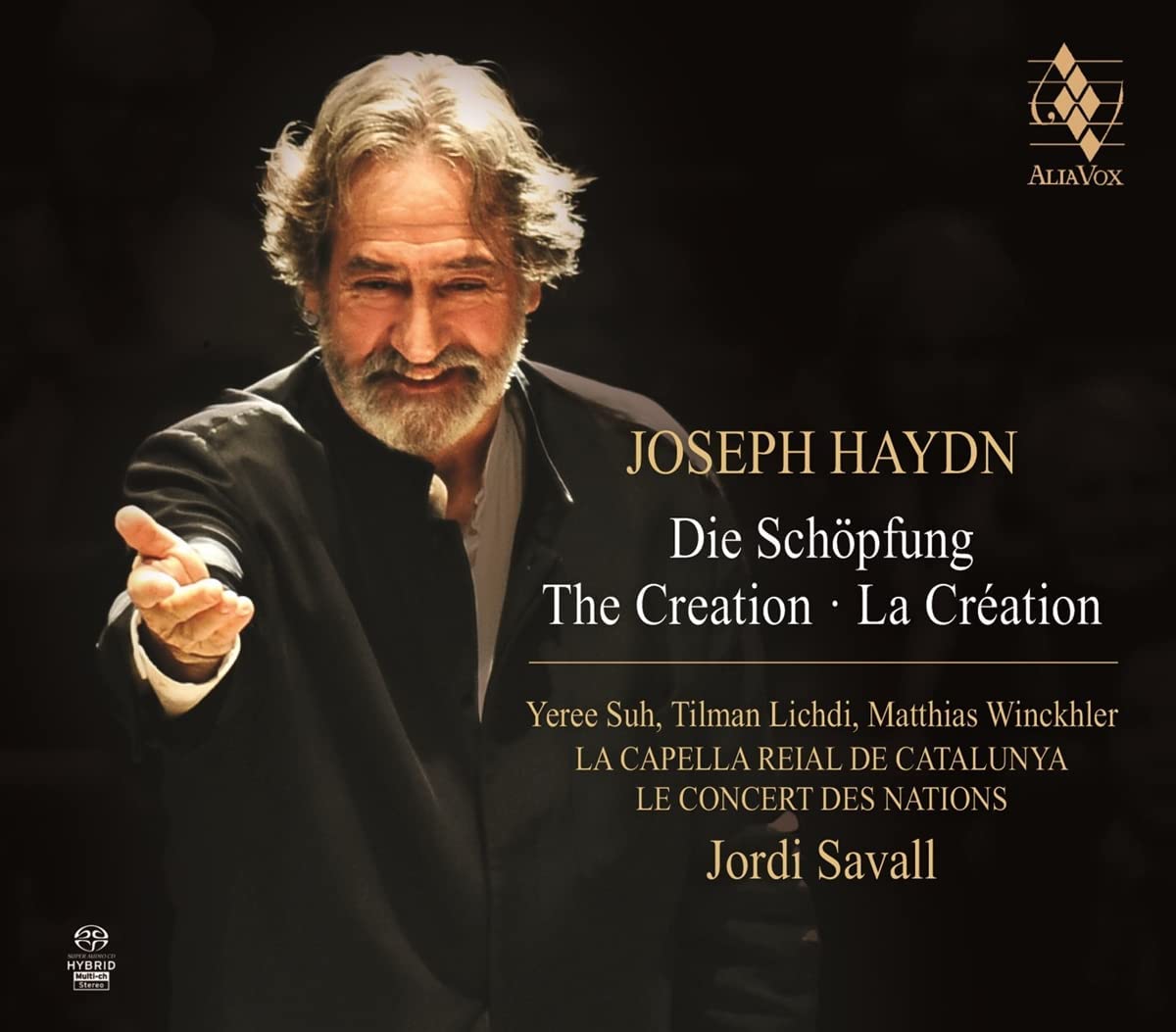

Yeree Suh, Tilman Lichdi, Matthias Winckhler, La Capella Reial de Catalunya, Le Concert des Nations, Jordi Savallq

103:18 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Alia Vox AVSA9945

Click HERE to buy this album on amazon.co.uk

[Doing so supports the artists, the record company and keeps this site available – if no-one buys, this ad-free site will disappear…]

Is there a more uplifting work in all music than The Creation? Even in a half-decent performance and for all the perceived naivety (by some) of parts of its text and the mimetic response they drew from Haydn, it juxtaposes glorious, iridescent power with reassuring companionability to a degree that is surely unique. Jordi Savall’s new recording, made shortly before his 80 birthday in May 2021, is, as one would expect, a great deal more than half-decent. The ethos of the performance is established at the very outset. Aided by the generous acoustic of the Romanesque church at Cardona in Catalonia, the portentous opening chord of the introductory ‘Representation of Chaos’ seems to last an eternity before finally dying. Again as one might expect, tempos are in general on the slow side, but only in Part 3 is there any feeling that there might have been more forward movement. In the opening duet with chorus for Adam and Eve that is more than mitigated by the manner in which Savall builds the movement to a magnificently controlled climax in the overwhelming outburst of praise to God, ‘Heil, dir’. Less convincing is the equally slow tempo for the more worldly duet that follows, ‘Holde Gattin!’, a wonderful example of the way in which Haydn throughout constantly alternates the godly with the world He has created.

This combination of the elevated, the spiritual with the everyday, the mundane world of cattle and worms, is to my mind at the heart of the humanity Savall finds in the oratorio. And time and again it is through the superb playing of his orchestra that he achieves that goal. Listen, for example, to the exquisite tenderness of the orchestral opening of the terzetto ‘In holder Anmut’ (In fairest raiment), so touching in its evocation of the beauties of nature and yet another number that will build inexorably, in this case from the pastoral to a glorious climactic point in the chorus ‘Der Herr ist gross’ (The Lord is great).

So where does that leave the soloists? Well, although all three sing well enough, particularly in ensemble work, I have to confess a certain disappointment. There is to my mind in common a shortage of strong personality, a lack of communicative skill that results in an inability to make the text tell in the way it can and must in this work. Most satisfying is the Korean soprano, Yeree Suh. Hers is a truly delightful soprano, fresh, youthful and supple enough to essay passaggi with fluent ease and turn ornaments with elegance. At her best, as in ‘Nun heut die Flur’ (With verdure clad), she is beguiling and charming, but overall she needed to pay more attention to enunciation. Tenor Tilman Lichdi’s Uriel is fine without ever challenging some of the outstanding singers of the role. The timbre is agreeable and he brings a pleasingly youthful lightness of touch to his opening aria, ‘Nun schwanden’ (Now vanish’), but in the magnificent accompagnato celebrating the division of night and day, the sun and the moon, the ear is constantly caught not by the singing but the orchestra’s magnificent evocation of sunrise and the mystery of moonlight. And so it is too with Matthias Winckhler, whose baritone is rather lightweight for Raphael’s music and is at times pushed to maintain a steady tone at Savall’s deliberate tempos. But I would not wish to over-exaggerate any deficiencies the soloists might have; by any standard their contribution is at the very least thoroughly acceptable.

I’ve not so far mentioned Savall’s splendid hand-picked chorus, here just 20-strong (considerably fewer than Haydn had at his disposal in 1808) but sounding more numerous with the aid of the acoustic. The catalogue is graced by a number of outstanding recordings of The Creation. This one, for the reasons suggested, is rather special, and joins them as the product of the cumulative experience of one of the great musicians of our day.

Brian Robins