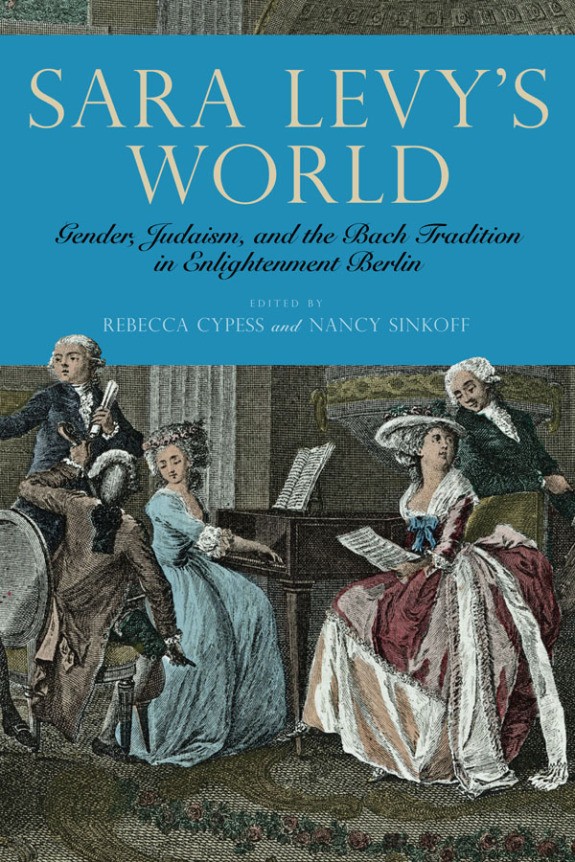

Eastman Studies in Music 145

Edited by Rebecca Cypess and Nancy Sinkoff

302pp. ISBN 978-1-58046-921-0 £80

University of Rochester Press, 2018.

This book is the outcome of a symposium in 2014 at Rutgers University. Eleven chapters, packed with information and extensive notes, attest to one of the cornerstones of musicological research: learned contributors excavate, analyse and explicate figures hidden from history.

Here the subject is Sara Levy (nee Itzig, as she signed herself in some of her few surviving letters). Madame Sara Levy (1761- 1854) was Felix Mendelssohn’s (he of the historic1829 performance of J. S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion) great-aunt. She died aged 94, had no children, and is a fascinating and significant figure for two reasons.

The first reason is musical. Levy was a friend and patron of the Bach family. She was a skilled harpsichordist, taught by W. F. Bach, and performed privately and publicly into her 70s – Charles Burney apparently heard her play. Her banker husband played the flute (alright for some), and they commissioned music from C.P.E. Bach. She had a remarkable collection of autographed music manuscripts and prints of the works of the Bach family, which she donated to the Sing-Akademie in Berlin (there is a photo of the house in the book). The collection disappeared, and was – finally – discovered, largely intact, in Kiev, in the Ukraine, in 1999.

Till then, Sara Levy was virtually unknown, However, Peter Wollny, director of the Leipzig Bach-Archiv, published a book about her in 2010 (in German, as yet untranslated, as far as I know). He is also responsible for the Grove entry on her.

Sara Levy was a significant figure for another reason. She was one of the salonnieres in the 18th-early19th centuries in Berlin. These salons were gatherings of friends, family and acquaintances, and they were cultural as well as social events: there might be discussions about books or politics, play-readings, and, of course, music. The salons were generally hosted by women, who were thus able to take part domestically in cultural activities from which they were excluded in the public sphere.

The added dimension to this part of musical/social history is that Sara Levy was one of an elite group of Jewish salonnieres in Berlin. Thus, as more than one chapter points out, she was part of a community of Prussian Jews who were involved in shared cultural activities with Christians – activities which straddle the two concepts of ‘emancipation’ and ‘assimilation’, in the process, as one of the chapters puts it, ‘of becoming modern Europeans’.

However, these oases of cultural coexistence should not be idealised. While there were conversions and intermarriage, there was also fierce controversy. Some of Sara Levy’s family became Protestants, but she remained steadfastly Jewish, though there is no evidence as to whether she was observant. She was involved in Jewish organisations, subscribed to the publication of Hebrew books and supported Jewish and Hebrew education.

At the same time, ‘she embraced Christian elements from German and European culture’. However, while some Jews ‘acquired a taste for church music’, and even had Christmas trees, ‘she and other Jewish women’s musical training (was) through Bach’s instrumental music’, rather than through compositions with Christian religious texts. Women were banned at the time from participating in Catholic and Protestant liturgical music.

It is clear that there were cultural tensions in operation, intertwined with the co-operations. Perhaps one of the most telling examples is the case of Mendelssohn himself. Baptised aged seven into the Protestant faith, at the age of twenty he was responsible for the revivalist performance in 1829 of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion, the story of the passion of Christ as king and Messiah, a challenge to Jewish theology. Contradiction and co-existence in a single piece of music. This historical period marked, as so many others have, arguments for Jewish tolerance alongside anti-semitism.

The book is fascinating, since, in the absence of autobiographical writings and other evidence, Sara Levy and her world are presented through an interdisciplinary perspective. It would have been great to have more information and gossip: was Sara present at the 1829 Passion? Did she know how Mendelssohn got the music in the first place? We will just have to imagine.

Towards the end of the book, an essay aims to clinch the cross-cultural argument by referring to the number of duets for various instruments in Sara Levy’s collection – including nine duets by Telemann which do not appear attributed anywhere else. These duets, it is argued, show that, in the equal balance of voices consists the metaphor through which an analogy and model for cultural co-operation is sealed. In turn, concepts of counterpoint and imitation, drawn from music, become metaphors for conversations between cultures. The images are elegant, anthropomorphic and musicomorphic (to coin a term).

While they function as an attempt to elide cultural and religious tensions, the book, in its carefully researched detail and variety of approaches, shows its subject, Sara Levy, as a social exception who serves to prove the musical rule, that women in music were rarely seen or heard. In this case, she is retrieved as having a crucial role in helping to generate, preserve and revive, the music written by the Bach family (all men, in case the point needs to be made!).

Michelene Wandor