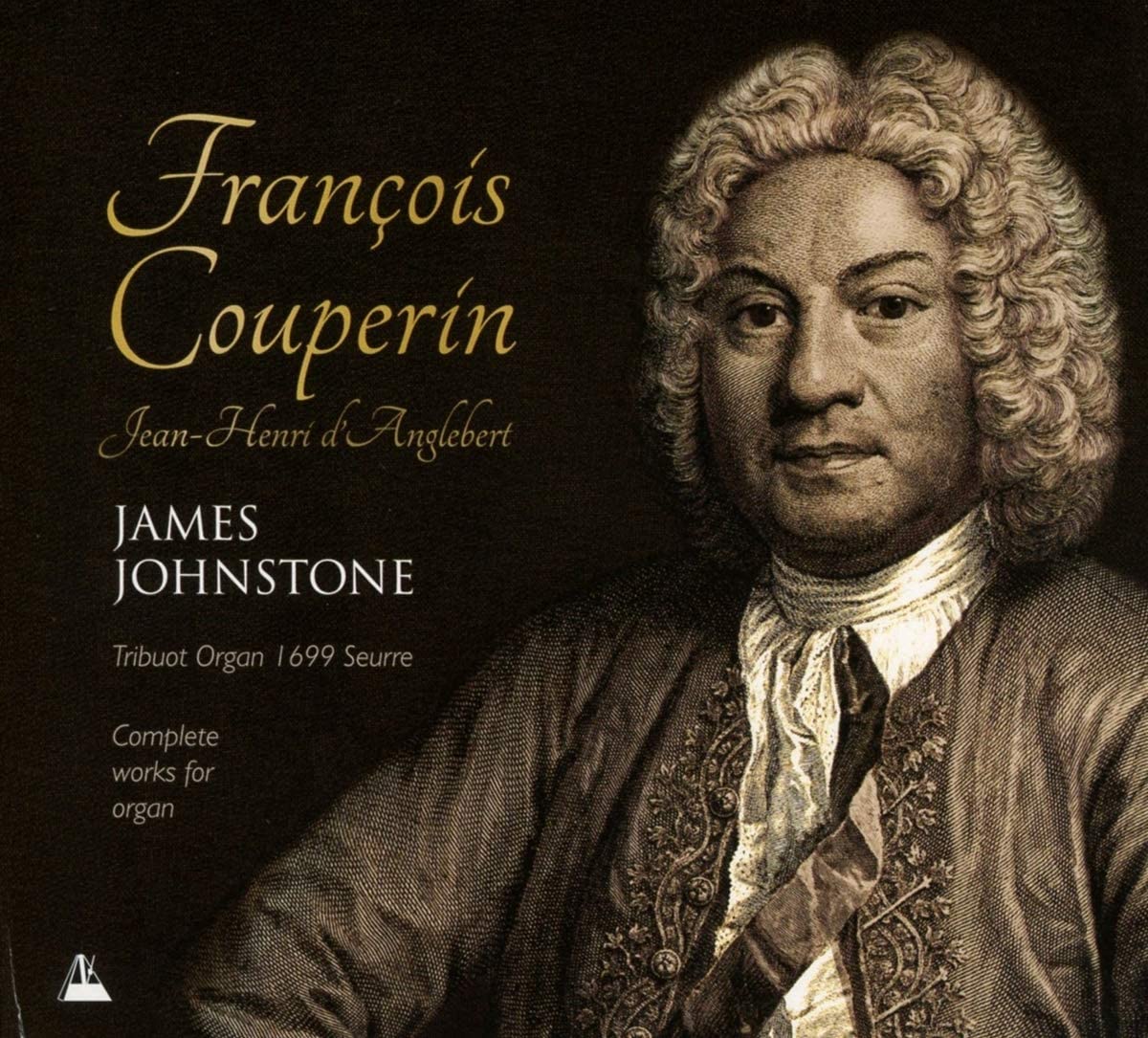

James Johnstone Tribuot Organ 1699 Seurre

100:59 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Metronome METCD 1098 & 1099

+ Jean-Henri d’Angelbert: Complete works for organ

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

In earlier reviews of James Johnstone’s organ playing, I have commented on the importance of finding a characteristic and appropriate instrument on which to perform the music, and this recording of the Couperin organ masses follows this tradition splendidly. The organ is neither well-known nor very large but turns out to be a gem by the Parisian builder Julien Tribuot. It was built for the Cistercian Abbey of Maizières in 1699 and was mercifully preserved when the abbey was dissolved by being sold in 1791 to the parish of Seurre on the Saône, where obscurity saved it from 19th- and 20th-century ‘improvements’, until its careful rehabilitation by Bernard Aubertin in 1991.

Like much else in the French organ music of the period, conventions for registration were detailed and highly prescriptive. Only on a French organ of the period can you hope to reproduce the required sounds with any accuracy and only a player who understands the conventions of notation and ornamentation in the period will get it feeling right.

I bought the L’Oiseau-Lyre edition of the Couperin Masses in October 1958 from UMP, and I remember struggling through some of it in a break-out room when a voice over my shoulder said, ‘No-one has taught you how to play this, have they?’ That was the legendary Felix Aprahamian, music critic and friend of Poulenc and Messiaen, who introduced me to the conventions of the ornaments and notes inégales, and fixed for me to go and play the Cliquot organ in Poitiers Cathedral. So my admiration for James Johnstone’s choice of instrument, disciplined approach to the registration and strict observance of the conventions of rhythm and ornamentation knows no bounds: he plays this repertoire with a detailed knowledge of the style on an appropriate organ that I’ve never heard before in an acoustic that allows the detail and flexible rhythms of his inégales to be appreciated and enjoyed.

This time too he has included not just the details of the specification of the organ in his booklet, but also full details of the registration for each movement on his website (www.jamesjohnstone.org). The pedal organ characteristically has reeds at 8’and 4’ pitch for use with the Plein Jeu and otherwise an 8’ flute; the 3rd and 4th manuals (Récit and Écho) have but a single stop on each – a five-rank cornet. We never hear the Écho cornet, and the flute on the Pedale is surprisingly insubstantial – it is a reconstruction, and I had expected something with a little more body for the bass of the movements en taille, but the robust Cromorne on the Positif en Dos is splendid and makes a surprisingly adequate balance with the Trompette and Clairon of the Grand-Orgue in the dialogue movements.

It is by the fluid rhythms of the recits en taille that I think players of this repertoire – which looks so plain on paper until it is brought to life by a player who has the conventions of late 17th- and early 18th-century French music in his bones – should be judged, and I think Johnstone has it. In his monograph French Organ Music in the Reign of Louis XIV (CUP 2011), David Ponsford analyses in great detail the genesis and development of the genres of the music of this repertoire, and shows how the styles relate to the quest in France for a living, breathing style that was capable of human emotion and expression.

This recording offers a perfect worked example, and I am very glad to have heard it. It is neatly produced and edited by Carole Cerasi, the harpsichordist and a fellow professor of Johnstone’s at the Guildhall. I particularly value Johnstone’s nose for sniffing out such high-quality, lesser-known instruments, and look forward to further discoveries for his Bach series.

David Stancliffe