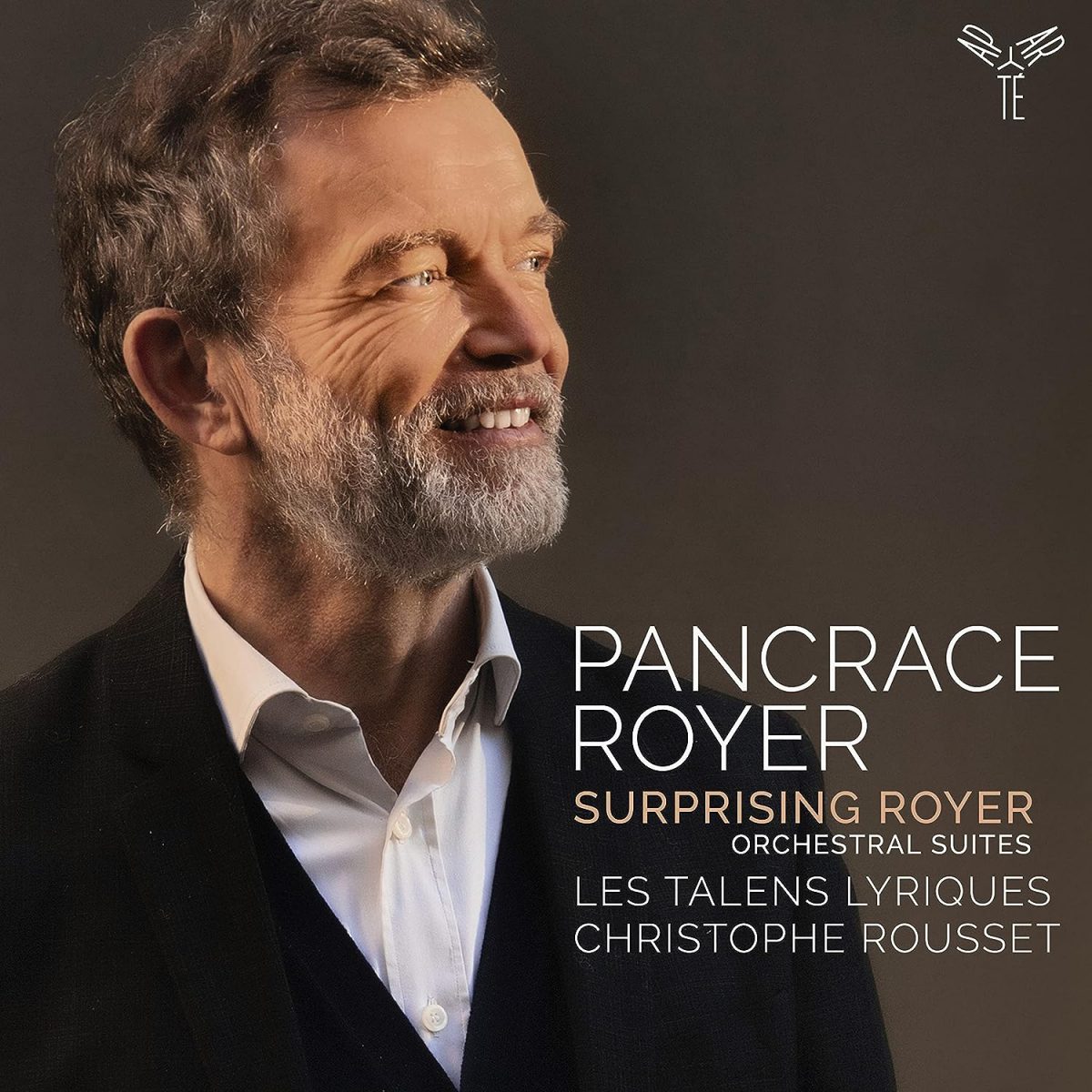

Les Talens Lyriques, directed by Christophe Rousset

82:07

Aparte AP298

It is not clear why it should be ‘surprising Royer’, Royer being Pancrace Royer (1703-1755). He was born of French parents in Turin, his father, an engineer, having been seconded by Louis XIV to assist the house of Savoy. The family returned to Paris while he was still a child. The connections with the royal family stood Royer in good stead; he became a teacher of the royal children, his links securing him his first opera commission, the tragédie Pyhrrus, composed to celebrate the birth of the Dauphin in 1729 and subsequently first performed at the Paris Opéra in 1730. That same year he was appointed maïtre de musique at the Opéra, where he oversaw the production of Rameau’s first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733). Later Royer would become director of the famous Parisian concert society, Le Concert Spiritual and the composer of a virtuosic and highly successful book of keyboard works that included transcriptions from his own operas.

They number five works in addition to Pyhrrus and from them Christophe Rousset has chosen orchestral extracts, mostly dances, from four: Pyhrrus, the ballet-heroïque Le pouvoir de l’Amour (1743), Zaïde, reine de Grenade (1739), another ballet-heroïque and the acte de ballet Almasis (1748). The opening overture to Le pouvoir immediately reveals a composer not only thoroughly competent in contrapuntal technique but also one with an impressive command of orchestration and orchestral colour. If Royer’s dances overall lack the supreme distinction of those of his contemporary Rameau – in particular we find only rare glimpses of the languid sensuality that is just one of many reasons for Rameau’s greatness as a dance composer – there are many that have thoroughly attractive qualities of their own. The two from a hunting scene in Zaïde that was apparently much applauded, an ‘Entrée des chasseurs’ and an ‘Air pour les chasseurs’ creating exciting evocations of the hunt, while some of the more extended dance movements are also particularly striking. Among these is a long and effective Chaconne from Le pouvoir that contrasts airy, diaphanous writing for the flute with more animated passages for the full orchestra. Another extended movement, an ‘Air tendrement’ again with restful trilling flutes and a counter melody featuring bassoons, is arguably the closest Royer comes to Rameau. And if you want irresistible verve, the two ‘Tambourins’ from Royer’s penultimate opera, the one-act Almasis fills the bill admirably.

To say that no one does this kind of music with the élan, the insight and the sensitivity that Christophe Rousset does has by now become virtually a cliché rather than an observation. Rhythms are sprung with refined grace, melodies shaped with elegance, but above all comes the feeling that dancers are never far removed from Rousset’s ‘mind’s eye’. Add to this superb orchestral playing by Les Talens Lyriques – just listen to the rich depth of the bass string section with its six cellos – and it becomes clear that this is a CD that needs no further endorsement from me or anyone else. If you have any kind of feeling for French baroque music you need to hear this. Post haste.

Brian Robins