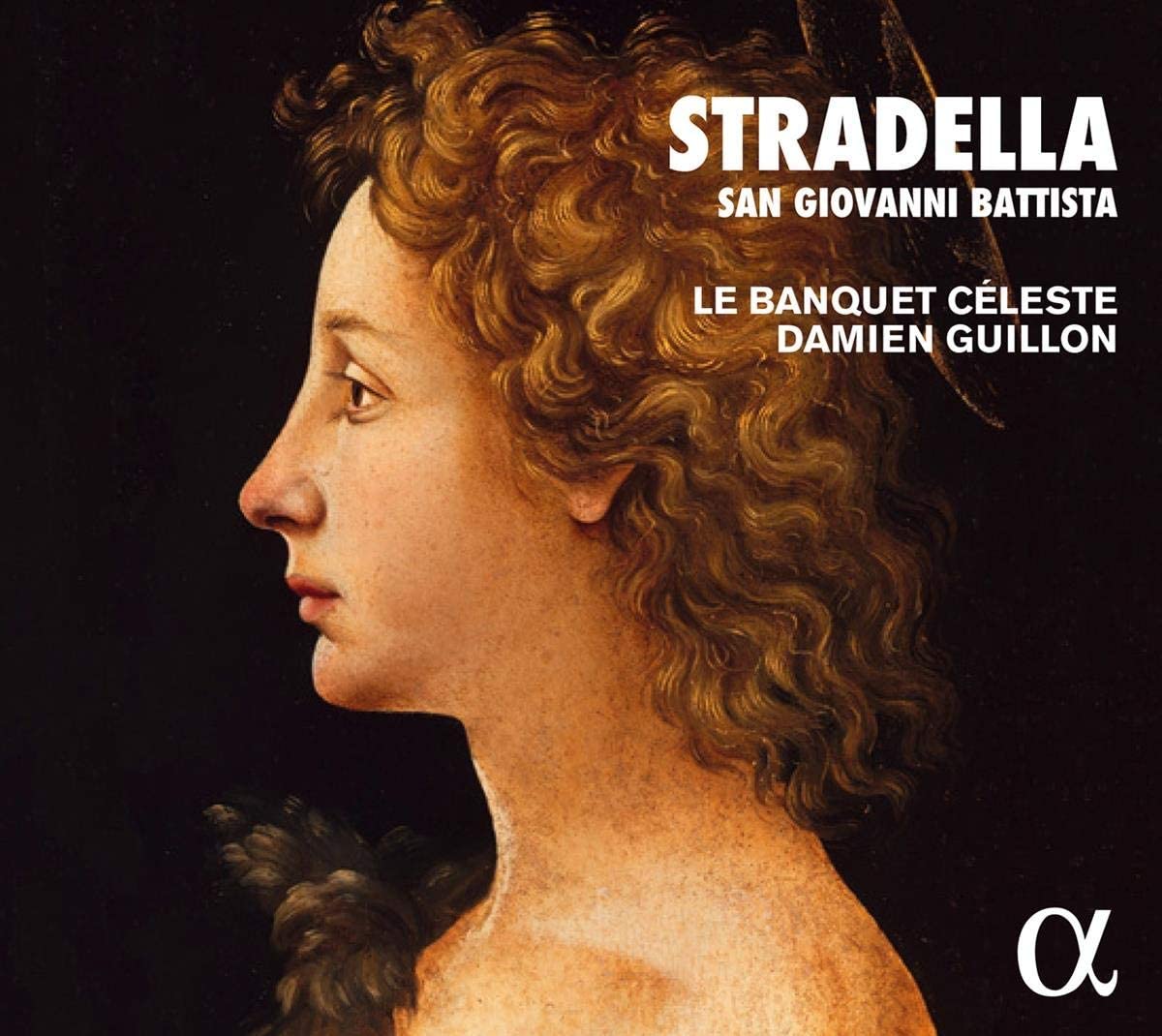

Le Banquet Céleste, Damien Guillon

80:42

Alpha 579

Click HERE to buy this from amazon.co.uk

Increasingly recognised as a major composer, Alessandro Stradella’s cause has benefited greatly from the conductor Andrea de Carlo’s ongoing Stradella Project, of which there are so far five volumes. Now from France comes a superlative performance of one of the oratorios de Carlo has yet to record. San Giovanni Battista, like all those of the composer, was composed for Rome, in this case in 1675 for the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini. In common with nearly all 17th-century oratorios the story of Herod’s beheading of St John the Baptist at the behest of his daughter (here called ‘The Daughter Herodias; although often known as Salome she is not named in the Bible) had a direct didactic purpose. Here however an outstanding libretto by the poet Ansaldo Ansaldi equally explores the more ambiguous aspects of the story, which ends with the question ‘E perché, dimmi, e perché’ (And why, tell me, why?) posed in a duet for Herod and his daughter, each from an entirely different motivation. In a score replete with telling musical dramatization, Stradella grasps the moment to leave the oratorio’s conclusion suspended in the air, unresolved.

Ansaldi’s libretto indeed concentrates strongly on the relationship between Herod and his daughter, in particular the stark contrast between the troubled soul of the king and youthful spirit and vitality of the girl. The role of Herodias is relatively restricted, while that of San Giovanni is almost detached in its other-worldly sublimity, fully engaged dramatically only when charging Herod with his sins. In its vision of his impending death, the baptist’s rapturous aria ‘L’alma vien’ conveys something of the same aura as Bernini’s sculpture The Ecstasy of St Teresa of a quarter century earlier. As remarkable is the supreme irony of the succeeding ‘sympathetic’ duet with Herod’s daughter, San Giovanni’s last words before death.

Stradella employs a bewildering variety of forms ranging from plain recitative to recitar cantando and arioso through to arias sometimes through composed, others in two contrasting parts and, in one case, San Giovanni’s ‘Io per me’, a three-part aria foreshadowing da capo form. The opening section is another of those almost other-worldly numbers, the central quicker section more animated. It is sung with rapt concentration by countertenor Paul-Antoine Benos-Djian, who is excellent throughout, here keeping an excellent sense of line, an attribute made the more challenging by the very languorous tempo taken by Damien Guillon. One of my very few question marks over the performance would in fact be Guillon’s lingering over some of Stradella’s cantabile arias, though so beautiful are most of them that it is a sin not too difficult to forgive.

The arias for the daughter are well varied. In the playful ‘Volin’ pur lontan’, an exhortation to Herod to return to pleasure, her guileless words are articulated in fleeting, fragmentary motifs underlaid by a quasi-ostinato bass, one of several examples. It is sung with delightful freshness by soprano Alicia Amo, who is equally at home in the more strident demands to Herod for the head of the baptist. ‘Deh, che più tardi’ (Ah, why do you delay?), is a vivid example of Amo’s dramatic powers, the words ‘e discolora’ inspiring a quite breathtaking chromatic portamento leading to a surprisingly powerful chest note. Here too are examples of one of the singer’s greatest assets, her exquisite mezzo voce, which is capable of real beauty even in her higher register. Bass Olivier Dejean’s troubled Herod is equally distinguished, at its imperious best in the fury of ‘Tuonerà tra mille turbini’, but almost sympathetic in his conscience-stricken final recitative, the last line of which is delivered with almost motto-like purpose, Ah, for repentance is the heir to error. His wife is capably sung by mezzo Gaia Petrone, although there is too much vibrato for my taste, while in the small role of the Consigliero, Herod’s councellor, tenor Artavazd Sargsyan takes full advantage of the marvellous ‘Anco in cielo’, its depiction of the Phoebus’ laborious daily journey across the skies depicted in graphic terms by relentless bass ostinato.

The playing of Le Banquet Céleste is exceptional throughout, though the single double bass seems at times to have been over-miked and the sound produced at the Abbaye Royale de Fontevraud is arguably a bit over- resonant. But such detail pales into insignificance in the face of this unqualified masterpiece and a recording of it that only serves to further underline the outstanding strength of early music in France.

Brian Robins