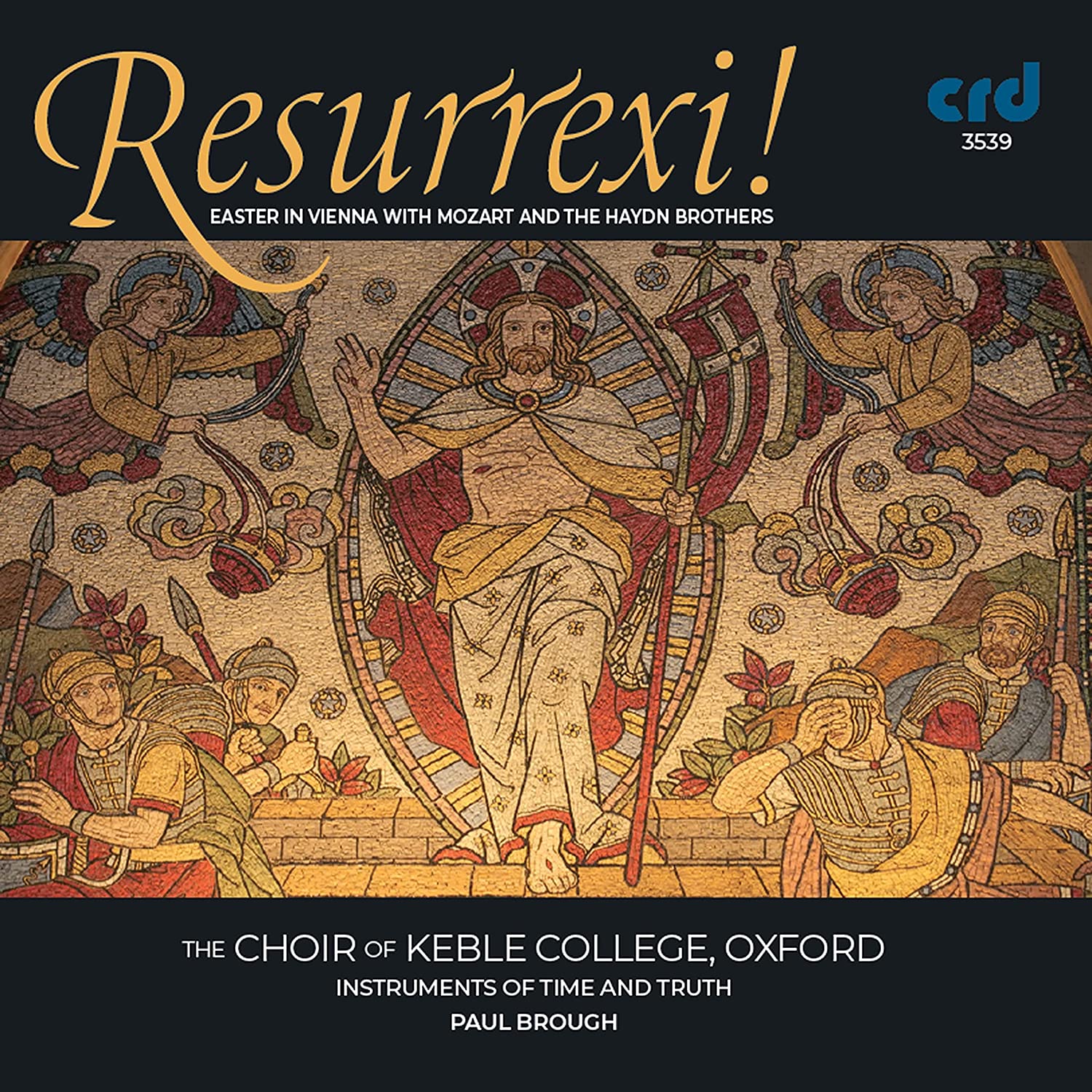

Easter in Vienna with Mozart and the Haydn brothers

Emily Dickens, Rebekah Jones, Philippe Durrant, Graham Kirk SmSTB, Choir of Keble College, Oxford, Instruments of Time and Truth, directed by Paul Brough

56:05

CRD 3539

Click HERE to buy this recording on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links are your only way to support the site and keep it FREE to access]

In an amusing and rather winning introductory note Paul Brough, the musical director of Keble College, disarmingly explains that the objective of this recording is not an attempt ‘to give a lesson in history, liturgy, theology or musicology’ but rather to bring to the listener ‘the powerful truth of Easter …’ That, then, is the spirit in which I will try to review it.

Despite the disclaimer, the recording will indeed recall to many the kind of liturgical reconstruction that was fashionable in the closing decades of the last century, especially the pioneering work of Andrew Parrott and Paul McCreesh. It is centred round the idea of how an Easter Mass might have been celebrated in Salzburg in the 1770s, though for some inexplicable reason the CD carries the subtitle ‘Easter in Vienna…’. It is planned around Mozart’s Mass in C, KV 258, which dates from the middle of that decade and takes its name from speculation that it is the Mass given at the consecration of Count Ignaz Friedrich von Spauer as Dean of Salzburg Cathedral in late 1776. Scored with trumpets and timpani, it is therefore a hybrid work, a so-called missa brevis et solemnis that although ceremonial in character conforms to the famous (or maybe infamous) dictum of Archbishop Colloredo that the entire Mass – including plainchant and additional liturgical movements – should not last longer than 45 minutes. Each of its movements is therefore extremely brief – the entire Gloria takes only 2½ minutes in the present performance – with little repetition of text and the brief passages for the four soloists mostly integrated into the choral texture, perhaps, as Stanley Sadie pointed out, most interestingly in the unusual antiphonal exchanges between soloist and choir in the Benedictus. It was a form that, as Mozart wrote to famous theorist Padre Martini of Bologna, required ‘a special study’ and not one that is likely to have appealed to him.

Otherwise choral settings include the opening Marian antiphon, Mozart’s C-major Regina coeli, KV 276/321b, composed in 1779 for an unknown occasion, joyously bright but for a brief appropriately prayerful digression at ‘ora pro nobis’. Of earlier provenance is the concluding Te Deum in C by Haydn, composed for an unknown occasion in the early 1760s during his first years of employment with Prince Nicholas Esterházy, possibly for the Prince’s official entry into Eisenstadt in 1762. It’s an unremarkable work in the somewhat stiff, old-fashioned Austrian style, and rather less striking than his brother Michael’s more modern gradual setting of the sequenza Victimae paschali laudes, composed for Palm Sunday in 1784. It was one of a series of such pieces commissioned by Colloredo to replace the string sonatas traditionally inserted between the reading of the Epistle – hence the commonly-used name Epistle Sonatas – and the Gospel. One of Mozart’s, KV 274 in G, is included here in a disappointingly prosaic performance in which the weedy chamber organ is no substitute for one of the four Baroque organs in Salzburg Cathedral.

It would be idle to pretend that the soft-grained sopranos of Keble College project anything like the visceral brilliance of continental boys, but the choir is a fine, well-trained and balanced body, while the four soloists capably meet the relatively modest demands made on them. Baritone Graham Kirk is an unexceptionable cantor, while the choir’s intoning of the plainchant is effectively if a little too deliberately done. Does it all perhaps sound a little too polite and Anglican? Well, maybe, but to go back to my opening paragraph on its own terms, this celebration of Easter in Mozart’s Salzburg amply succeeds in giving both spiritual and musical satisfaction.

Brian Robins