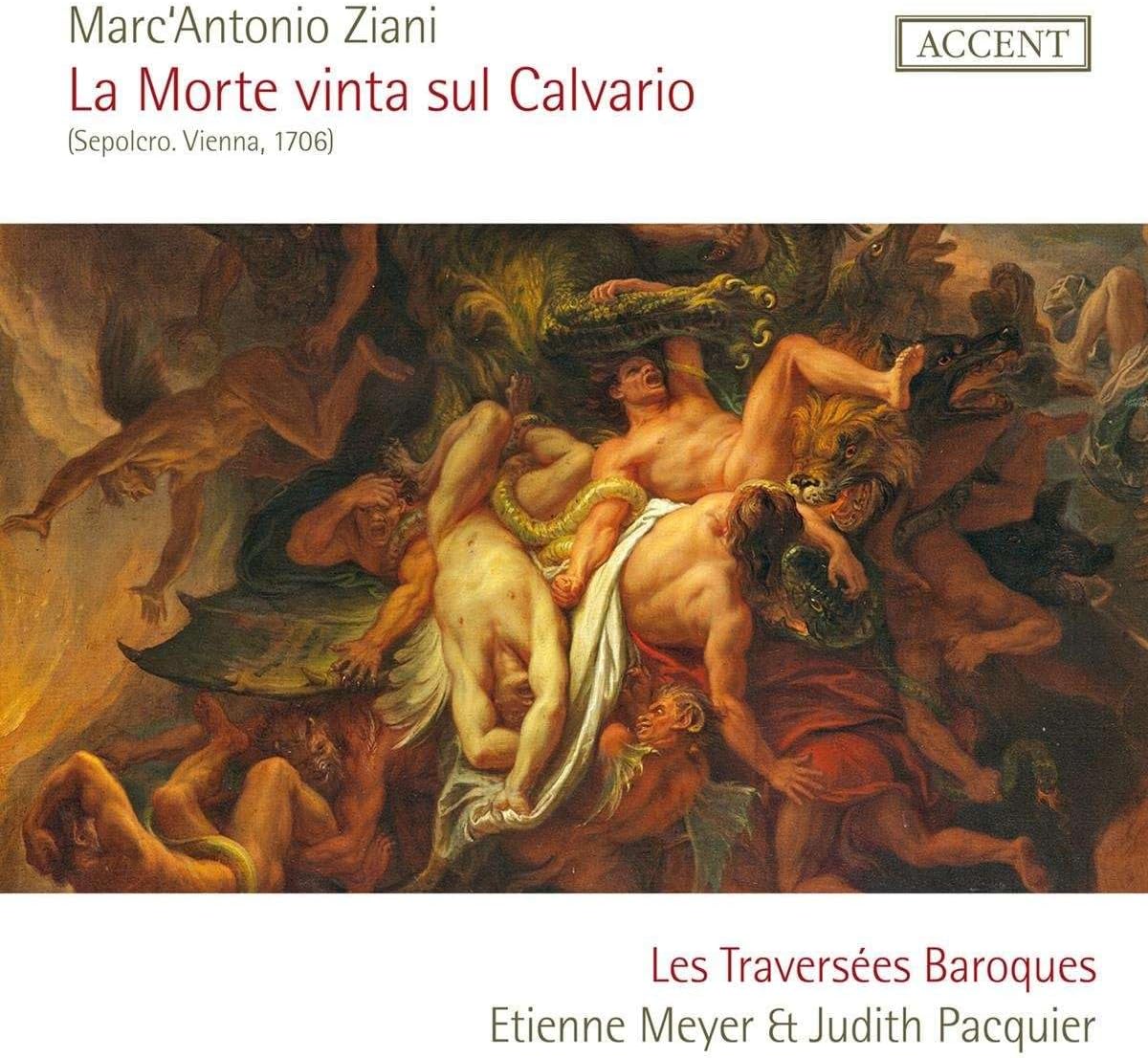

Les Traversées Baroques, directed by Etienne Meyer & Judith Pacquier

73:18

Accent ACC 24402

Often confused with oratorios, the sepolcro is a peculiarly Viennese form best thought of as a cross between opera and oratorio. The genre flourished at the Hapsburg court during the reign of the highly musical and deeply religious Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I (1658-1705), its best-known practitioners being Antonio Draghi (1634-1700) and Marc’Antonio Ziani (1658-1715). Sepolcri can be defined as semi-staged dramatic works performed on Good Friday in either spectacular fashion in the Hofkapelle or more intimately in the private chapel of one of the senior members of the Imperial family. The characters depicted were nearly exclusively allegorical, thus similar to the type of libretto familiar today from Handel’s early Roman oratorio La resurrezione (1708).

The Venetian opera composer Ziani arrived in Vienna in the wake of Draghi’s death, appointed vice-Kapellmeister in 1700. For the Viennese court he composed operas, oratorios and eight sepolcri. His La Morte vinta sul Calvario dates from 1706, when it was given in the Hofkapelle on the evening of Good Friday and has for its subject matter Christ’s triumph over death as a result of his dying on the Cross at Calvary. The topic is explored in P A Bernardoni’s libretto by five allegorical characters: Il Demonio (Satan), La Morte (Death), La Natura Umana (Human Nature), La Fede (Faith) and L’Anima d’Adamo (the Soul of Adam). The ‘action’ is carried on through alternating brief da capo arias and recitative, a typical sequence being aria-recitative-aria for the same character. There is also a duet (for Il Demonio and La Morte) and a final madrigalian chorus. A number of the arias are fairly florid, Il Demonio opening the work with a particularly bravura piece in a role sung at the first performance by the bass Rainaldo Borrini, one of the most highly paid singers at the Viennese court. The taste for contrapuntal writing at the court is much in evidence, with chromatic seasoning also strongly featured in Ziani’s score. Some of the cantabile arias have considerable beauty, La Natura Umana’s ‘Io languia’ (no. 30) being a particularly winning example. Accompaniments feature a rich assortment of brass and wind – pairs of cornetti, recorders, sackbuts and bassoons in addition to the strings, which include violas da gamba. It is a weakness of the present recording that only single strings to a part are employed, since we know sepolcri employed the substantial forces available at the Viennese court, which just a few years later is recorded as employing over 30 string players.

The demands made on the singers are in the main too great for the present performers, though the performance is obviously one of great integrity. Yannis François’s is a lightish bass-baritone whose voice carries neither sufficient authority nor personality for Il Demonio. La Natura Umana is sung by Vincent Bouchot, listed as a tenor but who, particularly in his first aria, sounds more like an haute-contre. La Morte, a countertenor part, is sung by Maximiliano Baños pleasingly enough but without making any significant impression. Much the most satisfying performances come from the two sopranos, Dagmar Šašková’s in particular bringing to the role of La Fede a sense of real commitment lacking elsewhere, along with some highly impressive chest notes in her angry recitative exchange with Il Demonio (no. 25). However, both she and the charmingly fresh-sounding L’Anima d’Adamo of Capucine Keller had difficulty controlling a few notes above the stave. The instrumental playing is good.

Although the performance is not ideal it is praiseworthy for its honesty and intentions. Les traversées Baroques deserve praise for reviving a splendid example of a repertoire little known today.

Brian Robins