Cinquecento Renaissance Vokal

71:06

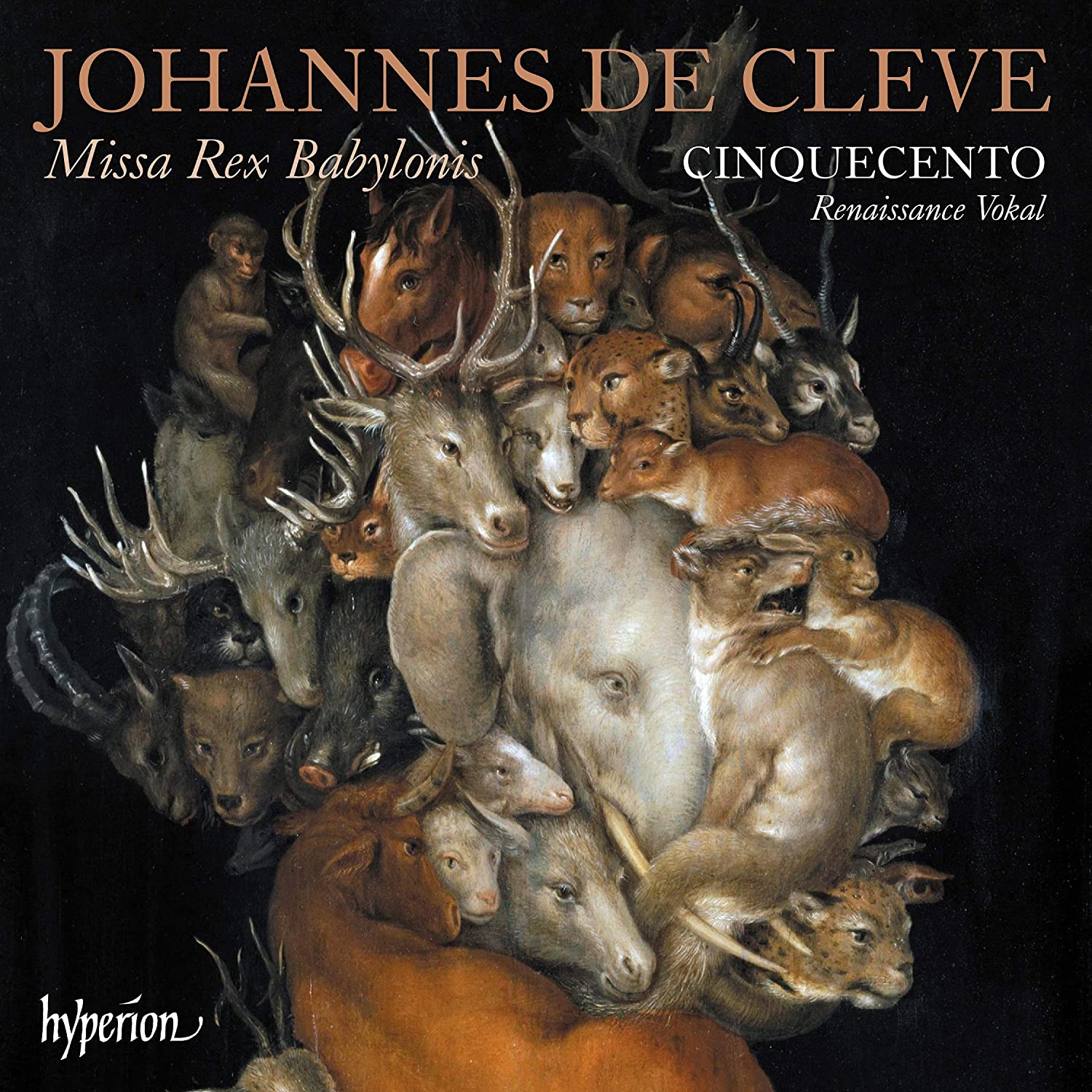

hyperion CDA68241

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Johannes de Cleve (1528/9-1582), while an almost exact contemporary of Palestrina, composed in a recognisably Franco-Flemish style, with its debt to Gombert and, earlier still, Josquin, while there are a few audible nods towards Italy. Originating from modern-day Kleve, the same neck of the woods as Henry VIII’s fourth wife, on the borders of modern Germany and the Netherlands, it is assumed that he was trained in the Low Countries before, in 1553, fetching up in Vienna and having his first book of compositions published in Antwerp. Their almost exact contemporary, the definitely Flemish Jakob Vaet (pronounced “vart”), born in what is now Kortrijk, also fetched up in Vienna, and provides the motet on which Cleve bases his mass. While Vaet is relatively well represented on disc, thanks in no small part to Cinquecento, Cleve is a virtual newcomer. Does his music deserve this extended recognition?

There is no getting away from the fact that Call-me-Vart is the better composer, for all his limited appearance on this disc. His motet lasts over nine minutes, and its sweeping musical narrative puts Cleve into perspective. In Cleve’s mass, there is a lack of subtlety in his use of salient features from Vaet’s motet which suggests that originality is in short supply. There is some stilted homophonic writing in the first section of Carole qui veniens just before some rather by-numbers syncopation, though there is compensation in a striking chromatic passage during the second section. That said, most of his works possess some good moments. His use of dissonance which, like his chromaticism, is touted in most commentaries about him, shows its head assertively in both settings of the Agnus in the Mass. The same animated and affecting Hosanna concludes the Sanctus and Benedictus. And there is some mellifluous polyphony in the Kyrie.

Recently for this journal, I reviewed a disc, sung by the Brabant Ensemble, of music by members of the Franco-Flemish wolf pack, Lupus Hellinck and Johannes Lupi (Hyperion CDA68304). Born three decades before Cleve, there are aspects of their music – fluency, spontaneity, originality, breadth and independence of creative thought – which make it superior to his agreeable competence. As for the performance, Cinquecento produce a rather thick texture and, as a male ensemble albeit with a falsettist, tend to gravitate to lower in the vocal range than a choir such as the Brabant Ensemble, which includes females, and whose renditions are a tad (very acceptably) rougher but whose vocal textures tend to be brighter. As I remarked in my recent review of Cinquecento’s recording of the second book of Palestrina’s Lamentations (Hyperion CDA68284), this rendered them perfect exponents for this more intense and static music, but it can lead to some monotony especially when applied to a composer such as Cleve.

Cleve’s well-wrought dissonances and chromaticisms, within his competent yet still conservative technique, earn him this revival by a major ensemble on a major label. Other composers tell a better story over the piece, but even a lesser composer within the Franco-Flemish School, albeit right at the end of its span, is better than a lesser composer from most other such circles.

Richard Turbet