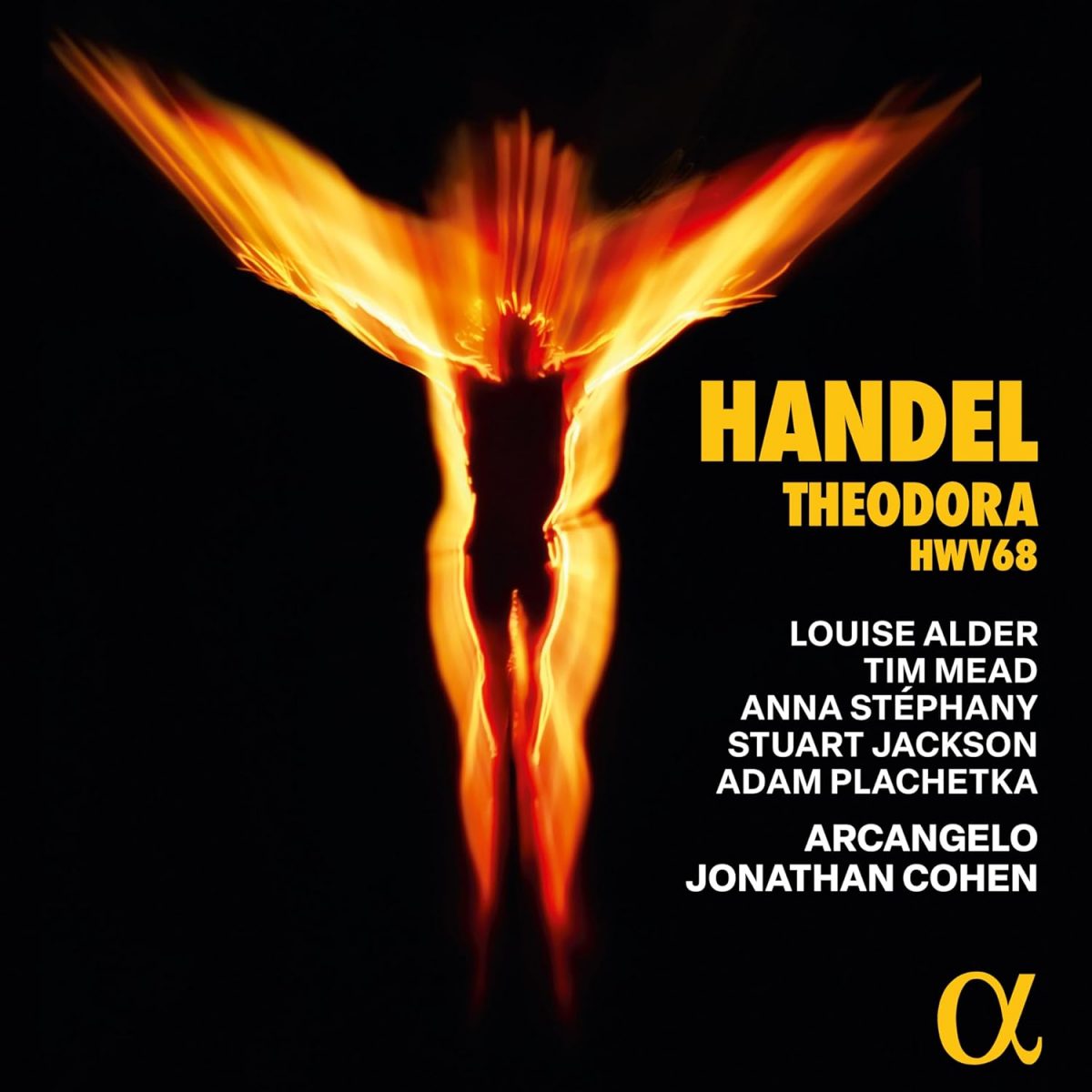

Louise Alder Theodora, Anna Stéphany Irene, Tim Mead Didymus, Stuart Jackson Septimus, Adam Plachetka Valens, Arcangelo, conducted by Jonathan Cohen

178:32 (3 CDs)

Alpha Classics ALPHA 1025

I concluded the review of the last recording of Handel’s Theodora I wrote for EMR with the words that it was a recording ‘to which I hope to return on many occasions’. It would be pleasing if it were possible to write something similar about this most recent issue but I fear it is not. Given that I provided an extensive background to Handel’s penultimate oratorio in that review, I’ll here just remind readers that it was first given at Covent Garden in 1750. It has a libretto of variable quality by Thomas Morell and was not generally liked by Handel’s audiences, although it became one of the composer’s favourite works. Today opinion tends to side with Handel. It has also become fashionable to stage Theodora, often controversially.

The Erato recording was a rare take on a Handel oratorio by an international cast (the Irene was Joyce DiDonato, who played the part in the recent Covent Garden staging) that shone new light on the oratorio by approaching it from a more dramatic, operatic viewpoint than we customarily hear in concert performances. Cohen’s recording takes us firmly back into mainstream oratorio territory as it is viewed currently. Overall it is a fair reflection of the state of early music performances in the UK since they fused with the mainstream. There are some good voices – that of Louse Alder’s Theodora in particular has a freshness and tonal quality that is especially appealing – but, with the exception of countertenor Tim Mead’s Didymus, all display continuous, often wide vibrato. There is little suggestion that any of the singers involved has a background or training much associated with Baroque repertoire, the articulation of passaggi frequently lacking clarity, while waiting for anything as exotic as a trill is akin to waiting for Godot, Mead again excepted. To be fair there are one or two embryonic attempts scattered through the performance, in at least one case coming from a singer whose vibrato is so wide it is difficult to tell what we are hearing. Diction is universally poor, ironically the best coming from the only non-native singer, the Czech bass-baritone Adam Plachetka, who sings the part of the Roman governor Valens with ripe relish.

Jonathan Cohen’s direction adopts tempos that veer to opposite extremes, those for excessively slower speeds often incorporating sentimental mannerisms. But for my ears the worst sin of all is that he fails to inspire those singing Christian sentiments, either soloists or choir, into expressing the kind of luminescent joy Handel so memorably conveyed in his music, where he captures the near-incandescent rapture and commensurate danger that the early Christians found in their faith. ‘New scenes of Joy come crowding on, while sorrow fleets away’, sings Irene as Theodora is led away to her death. Not here. Obviously given contemporary mores, the music of the heathen Romans with which Handel so brilliantly contrasts the Christian passages comes off more convincingly, particularly the orgiastic choruses. Finally, to return to practical considerations, Cohen has committed the cardinal sin of not just including a superfluous lute in the continuo, but allowing it to be unforgivably obtrusive.

I’ve probably been unduly harsh on this performance. Listeners and critics inclined to mainstream performance will almost certainly value it more; indeed I’ve seen notices that overrate it to a grotesque degree. But I’m here writing for a readership presumably interested in HIP performance and from a personal viewpoint that the recording sadly mirrors the current poor state of early music in the UK. Fortunately there is always McCreesh’s superlative Archiv recording to which we can return, while the Erato makes for an interesting variant.

Brian Robins

2 replies on “Handel: Theodora”

Dear Brian,

Assuming a product isn’t an outright fraud or rip-off, I’ve always felt that trade criticism should start from a place of general supportiveness. This review rests on the (to me somewhat startling) contention that early music in the UK is currently in a poor state, possible due to the contention that early music in the UK has fused with the mainstream. Your other EMT reviews don’t give much insight into this general point of view; you almost exclusively review non-UK recordings. So one is left wondering as to what your general beef is and, whatever it may be, why you’d choose to put yourself in for three CDs of something apparently predetermined to inspire, in your own words, “undue harshness”.

If you had approached this recording in a better temper, you might have written a fairer review, starting with a fairer appreciation of ‘Theodora’. Thomas Morrell’s libretto, when you read it, is highly consistent in its quality, and actually of a notably high quality when you consider the period’s peculiar tendency to bathos. On the other hand, you could tighten up the assertion that Theodora “was not generally liked by Handel’s audiences” – it was a flop – and caveat the statement that “it became one of the composer’s favourite works” by noting that the only recorded sources for this information are secondary and, in the case of the librettist, a teensy bit biased.

We probably could never have dodged your customary darts regarding vibrato and trills, which appear across several of your reviews and reassure me that whatever the failings of the UK early music scene, at least in this regard, in your estimation, Arcangelo is on a par with Europe. As for the sinfulness of lutes, I can’t forget your mistake in your previous review of our Handel’s ‘Brockes Passion’ that we used a double-lute continuo (we didn’t, we used one lute, two players participated across the sessions because of availability) and wonder whether your animus here came pre-loaded, or whether you just need to dial down the treble on your hi-fi.

All in all, I’m reminded of the essential distinction between Historically Informed Performance and Hysterically Embalmed Preoccupation, and find it regrettable that a reviewer with such manifest deep love and knowledge should have got so far snarled up in the tree-roots as to ignore that he’s in the wrong wood, and being a bit rude to the squirrels.

With best wishes,

Julian Forbes

Brian Robins replies:

Dear Julian

Thank you for your response to the Theodora review. However I fear our views frequently diverge from your opening sentence onwards. I’m not sure what you mean by ‘trade criticism’; my work as a critic is not and never has been subject to any kind of affiliation with the music business or the artists involved in it. Particularly contentious is your suggestion that one starts criticism from a position of ‘general supportiveness’. No, good criticism should start from a position of neutrality and open-mindedness as far as the artists are concerned. Our sole ‘supportiveness’ should be to the composer, to try to ensure that, to the best of our knowledge, his intentions are being rendered as faithfully as possible. But I think your point is an important one and symptomatic of the notion, fashionable among many so-called critics today, that we just rubber-stamp performances with degrees of excellence. Thus far too many writers fail in their critical duties. I strongly believe this is bad for music and has lead increasingly to performers thinking they are above criticism, an unhealthy situation. Learn from the advice of the great 18th-century singing teacher Pier Francesco Tosi: Abhor the Example of those who hate Correction; for like Lightening to those who walk in the Dark, tho’ it frightens them, it gives them Light (Observations on the Florid Song, 1723).

I think if you approached other thoughtful people in the music world you’d find my suggestion that early music – indeed music in general – is currently in a poor state in this country not so startling. Indeed that you find it startling is in itself depressing. As is your sarcastic paragraph about dodging my ‘customary darts’ regarding trills and vibrato (ironically the author of the most trenchant anti-vibrato book thinks I’m far too lax on the topic!). It seems few people in early music today understand the supreme importance of the trill, which was not an option but an essential part of a decent singer’s armoury. We know from a Roman conservatory that the trill was practised for an hour every morning. I doubt many singers of early music today have practised trills for an hour in their lifetime! Incidentally, my error about the lute(s) in the recording of ‘Brockes’ Passion’ came about because of misleading information in the booklet, which lists two names without any clarification. Given such an error, I doubt many would have gone against the information provided when it is quite easy to confuse the sound of one lute with two on a recording. But this is not really the point, which is that the current pervasiveness of the continuo lute, often where one is not required at all, and the narcissism of performers who don’t care about encroaching on vocal lines is one of the great early music curses of our day.

So I think rather than employ clever if glib expressions like Hysterically Embalmed Preoccupation – which smacks of a head-in-the-sand attitude – it is time to look inward and start to try to recapture the spirit of quest and learning that motivated the great generation of HIP explorers.