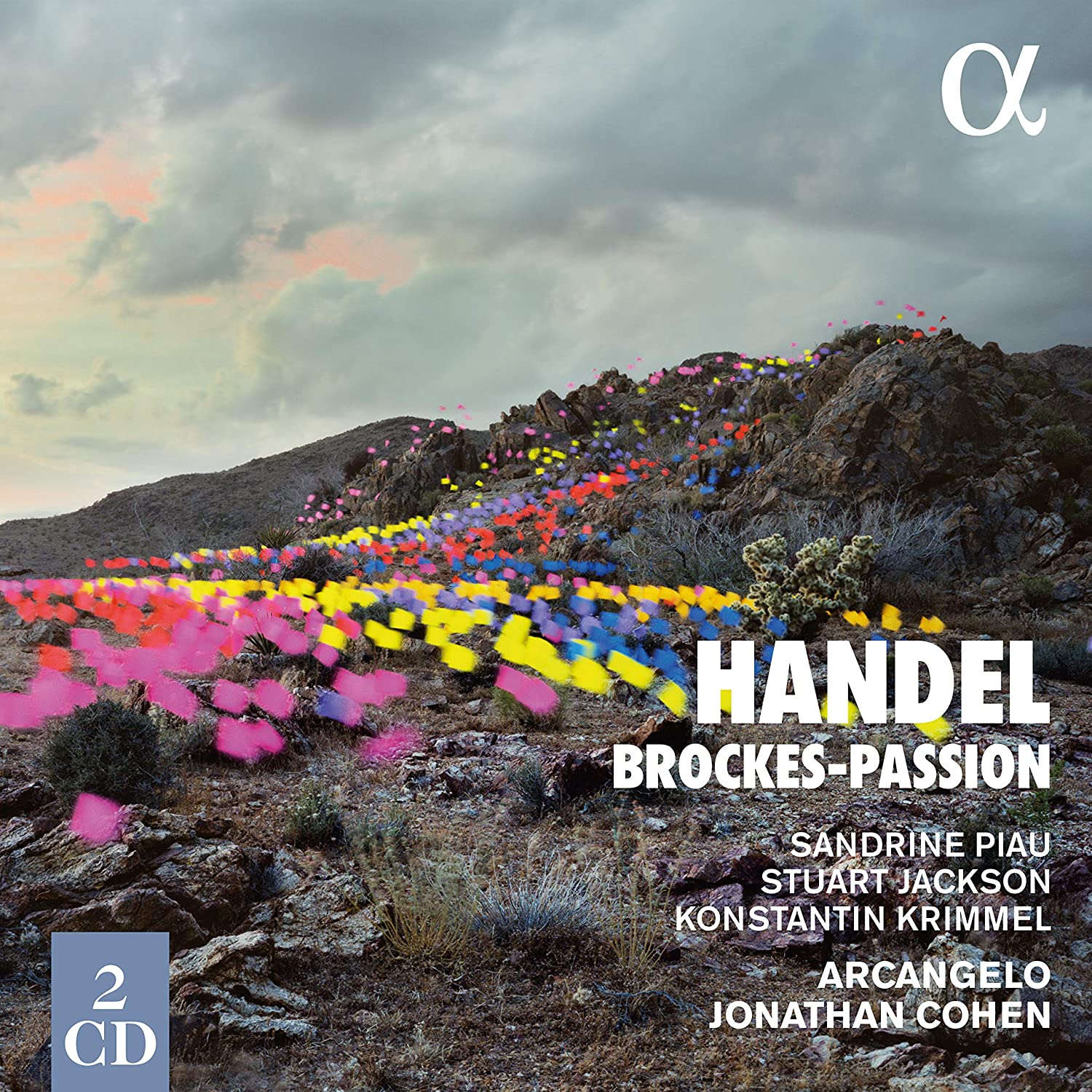

Sandrine Piau Tochter Sion, Stuart Jackson Evangelist, Konstantin Krimmel Jesus, Arcangelo, Jonathan Cohen

160:46 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Alpha Classiques Alpha 644

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links keep the site alive – and FREE! – go buy it!]

The Hamburg poet Barthold Heinrich Brockes’s passion oratorio Der für die Sünde der Welt gemarterte und sterbende Jesus, more conveniently known as Brockes-Passion, was first published in 1712. Possibly written for Reinhold Keiser, who set the text for Easter that year, in succeeding years it was taken up by some of the most notable German composers of the day, including Telemann (1716), Mattheson (1718), Fasch (date unknown) and Stölzel (1725). Handel’s setting, of which the autograph is lost, is strikingly lacking documentation, neither the date nor purpose of its composition being known. It is usually tentatively assigned to c1716, a year in which Handel made a return visit to his native country, but the first record of it being performed comes only three years later when it was given in Hamburg in the spring of 1719, on 3 April according to David Vickers’s notes, but 23 March according to Christopher Hogwood’s monograph on Handel.

Brockes’s text is a free paraphrase on Jesus’s passion drawn from the gospels but, as its full title suggests, infused with strong Pietist sentiment. It has three principal solo roles: soprano (Daughter of Zion), tenor (Evangelist) and bass (Jesus), in addition to which there are smaller parts for an allegorical Faithful Soul, Peter, Pilate and other figures familiar from the dramatic events. In keeping with more familiar gospel settings, the narrative is carried forward by recitative, with arias that complement the drama or comment on it. Mostly brief and syllabic – there is relatively little bravura writing – these arias are generally either through-composed or strophic in the German manner, but a number adopt Italianate da capo form. A surprising aspect is the comparatively small role given to the chorus, restricted largely to its role in the drama or an occasional chorale. Most modern commentators have tended to be less than complimentary about Brockes’s text. Indeed some of the more lurid or fanciful verse holds little appeal today, such passages as the recitative castigating the crown of thorns for its cruelty – ‘Foolhardy thorns, barbaric spikes! Wild murderous thicket, desist!’ – more likely to raise a smile than empathy. But it is of its day; more curious are dramatic weaknesses that depart from the narrative for substantial stretches to comment and observe, the long sequence of aria-recit-aria-recit-aria, for the Daughter of Zion that includes the words just quoted not advancing the story in any sense. Then there is the mystery of the missing Jesus, who having played a full role in the first half disappears entirely in the second with the exception of a pair of brief duets, the first with the Daughter, the second with his mother Mary, the poignant final words from the cross assigned to the Evangelist.

Although it – needless to say – includes some splendid music, this strange, dramatically weak book did not inspire Handel to the full extent of his powers, although he did find sufficient in it to reuse a substantial amount of music in the later oratorios Esther and Deborah. But it is probably best summed up by Handel expert Winton Dean in his seminal study on the dramatic oratorios: ‘In the Brockes-Passion Handel comes nearest to challenging Bach, and retires discomforted’.

Arcangelo’s performance is a mixed blessing. On the credit side is the scale of the performance, with a small orchestra and vocal ensemble of two voices per part. That is much what we might have expected to find in a Hamburg performance in 1719. There is also the intrinsic quality of the singing and playing, both of which are outstanding. Give or take the usual caveats about some unconvincing ornamentation (or lack of it altogether; you’ll hear one vocal trill throughout the performance), the three main soloists are splendid. The beautifully sustained lines of Sandrine Piau’s cantabile in the more reflective arias gives special pleasure, while the rich nobility of Konstantin Krimmel’s Jesus is scarcely less memorable. The vocal ensemble, from which the well-delineated smaller roles are drawn, includes such notable names as sopranos Mhairi Lawson and Mary Bevan and is also excellent in the choruses.

Sadly such quality is compromised by a number of questionable directorial decisions, not least the excessively slow and at times mannered tempos adopted for far too many arias and, arguably worse still, recitative, which at times drags unconscionably, thus rendering Stuart Jackson’s fine Evangelist less imposing and authoritative than it would otherwise have been. Jonathan Cohen’s inexplicable and almost certainly ahistorical decision to employ two (!) lutes in his continuo was a major error that recalls the memorable words of EMR’s late founder – ‘silly pluckers!’ Here their arpeggiating, twiddling contribution is irritating at best and vulgarly intrusive at worst, as in Jesus’s intensely moving accompaganto, ‘Das ist mein Blut. Such scars regrettably prevent me from giving the set the recommendation its performers deserve. Those less concerned about my strong reservations regarding both work and performance will find the set a good introduction to one of Handel’s lesser large-scale works.

Brian Robins

2 replies on “Handel: Brockes Passion”

Dear Brian,

Thank you for the review. Just to correct one small important (though understandable) mistake: The booklet does not explain that although two lutenists are listed in the player roster, only one is playing at any one time (there were availability issues during the sessions, and we recalled the memorable words of EMR’s late founder that “one plucky plucker is better than pluck all plucking” ). Please be careful with words like ‘twiddling’ when arpeggiating at the typewriter, skilled twiddlers could read them and get upset, perhaps simultaneously.

With best wishes,

Julian Forbes

Interesting! This was Radio 3’s Disc of the Week, last week! The text itself is a real “roller-coaster” of fire & brimstone, with some truly visceral imagery, I recall the bear’s claws and broods of vipers! It was assumed in some quarters that there had been a strange competition set up between Mattheson and Brockes, to see whose composition would carry the prize? There’s a special “Pasticcio” version (given at Hamburg in 1722) which contained elements of at least four different settings! And it is said the very earliest of Telemann’s Hamburg passions (1722-6) also contained sections from this work. What I found very salient from your misgivings that emerged perhaps via directorial decisions/input fascinating because, when Rene Jacobs did Telemann’s again, he truncated it a fair bit, but kept the action going at quite a lick! Missing out a few of the later beautiful arias, but the drama & pathos were kept intact! Nice in-depth review!