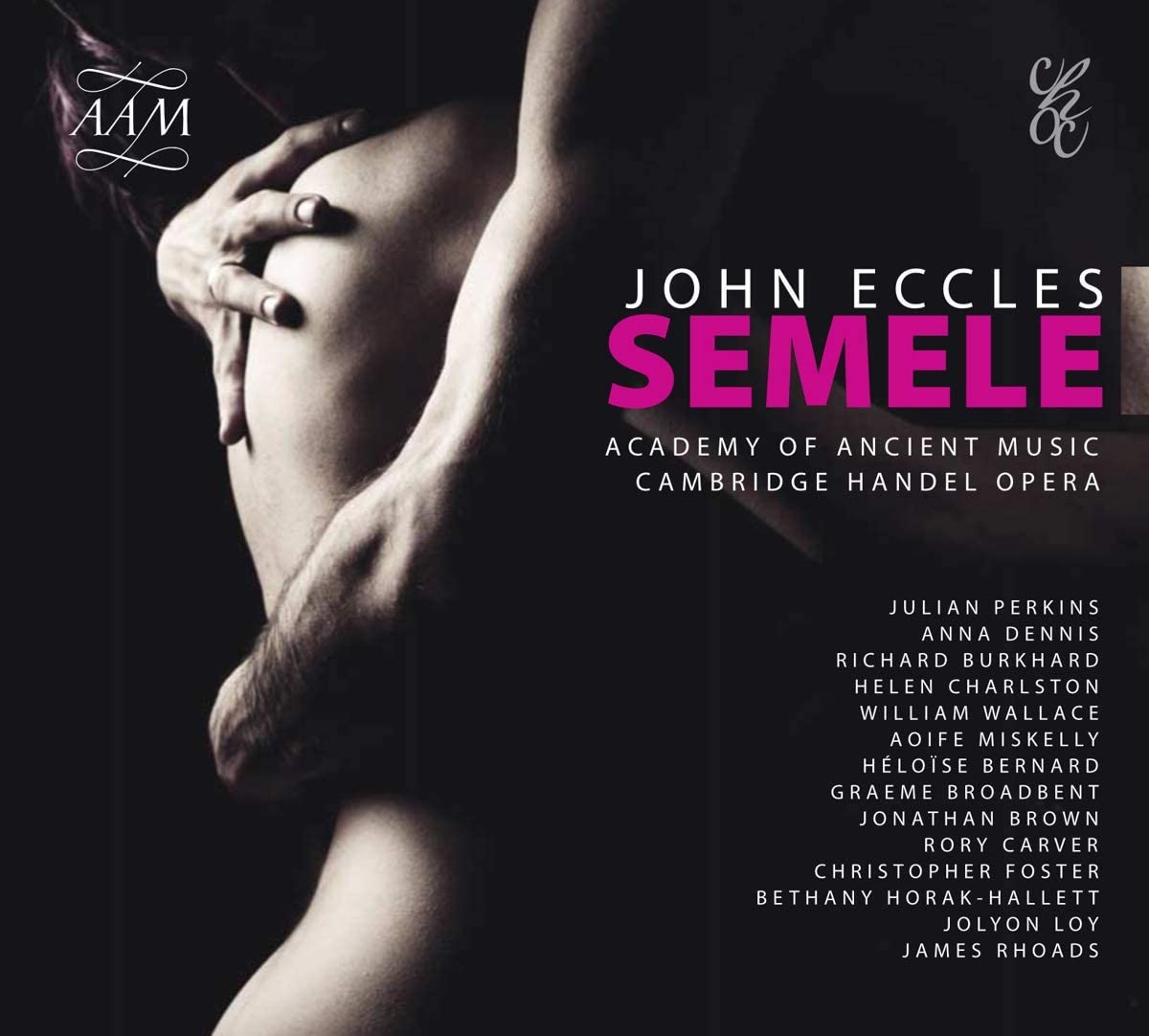

Anna Dennis, Héloïse Bernard, Aoife Miskelly, Helen Charlston, Bethany Horak-Hallett, Rory Carver, James Rhoads, William Wallace, Jonathan Brown, Richard Burkhard, Jolyon Loy, Graem Broadbent, Christopher Forster, Academy of Ancient Music, Cambridge Handel Opera, Julian Perkins

121:27 (2 CDs in a triptych in a folder with a hardback booklet)

AAM012

Click HERE to buy this album on amazon

[These sponsored links help the site remain alive and FREE!]

John Eccles has been the victim of historical bad timing. Following immediately after Purcell, on whose operatic writing he built very directly, his operas, and Semele specifically, were utterly overshadowed by the arrival in London of Handel. Handel’s own Semele served specifically to eclipse Eccles’s, which had to wait until the 1960s to receive its first performance. By this time the manuscript was incomplete, but it soon became apparent that this was one of the great ‘what-ifs’ of English music. Had Eccles’ Semele, setting a libretto by Congreve no less, been performed in the early 18th century, and earned him the accolades they both deserved, might truly English opera (in English and in the English tradition established so promisingly by Purcell and Blow) have survived to compete with Handel’s Italianate offerings? It is fascinating to hear the degree to which Congreve and Eccles choose the truly tragic route through the familiar myth, while Handel takes a generally more lightweight approach. Eccles Semele has been recorded before, but the present Cambridge Early Music package, with its extensive collection of related essays and a line-up of superb soloists from the Cambridge Handel Opera and the ever-excellent Academy of Ancient Music truly puts Eccles’ opera on the map. The dramatically powerful and musically persuasive performance is directed by Julian Perkins, who at the opposite end of the scale has delighted audiences up and down the country with his clavichord playing, here conducts with considerable authority. There are few Baroque performers who have not dabbled in the music of John Eccles – perhaps sometimes even initially due to his novelty name – and been impressed with his musicality, but his Semele demonstrates an altogether more impressive level of inspiration and musicality. My one slight reservation about this otherwise exemplary issue is that the one or two ensemble items sound a little too ‘close’ and vocally competitive. Otherwise, I think you can tell that these are young singers who are used to staging the opera of this period, and if the Eccles hasn’t yet made it to the Cambridge boards, the sense of unfolding drama is palpable on these two intense and engaging CDs.

D. James Ross