Ascioti, Baráth, Lombardi Mazzulli, Enticknap, Sacchi, Accademia Bizantina, Ottavio Dantone

160:46 (2 CDs in a single jewel case with booklet in a cardboard sleeve)

cpo 555 309-2

(Innsbruck Festival 2019)

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Venetian opera of the second half of the 17th century was marked by a remarkable flexibility of form involving recitativo cantando (sung recitative of the type familiar from the operas of Monteverdi) arioso and aria, the last often in strophic form. Frequently all three were seamlessly integrated and alternated to create fast-moving action involving both serious and comic episodes in which text was rarely subject to all but a minimal amount of repetition. Even more than Gluck’s so-called ‘reform’ operas, Venetian opera came close to realising a prototype of Wagner’s ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk over 200 years before he formulated it.

Although many composers were active in Venice and beyond during the period, two names in particular stand out: those of Cavalli and Cesti. Of the two Cavalli is today by far the better known, a number of his operas have been revived in more recent times. Pietro Antonio Cesti remains a more shadowy figure, this despite having composed two of the most successful operas of the entire century, Orontea and La Dori. His relative obscurity may at least in part be accounted for because his greatest successes were composed not for Venice – thereby leaving him less explored by writers on Venetian opera – but Innsbruck, where he served the Archduke Ferdinand Karl from 1652 until 1657, and Vienna, where he was put in charge of theatre music in 1666. Both Orontea and La Dori date from the Innsbruck period, premiered in 1656 and 1657 respectively, but both became widely performed throughout Italy, La Dori achieving at least 30 productions by the 1680s.

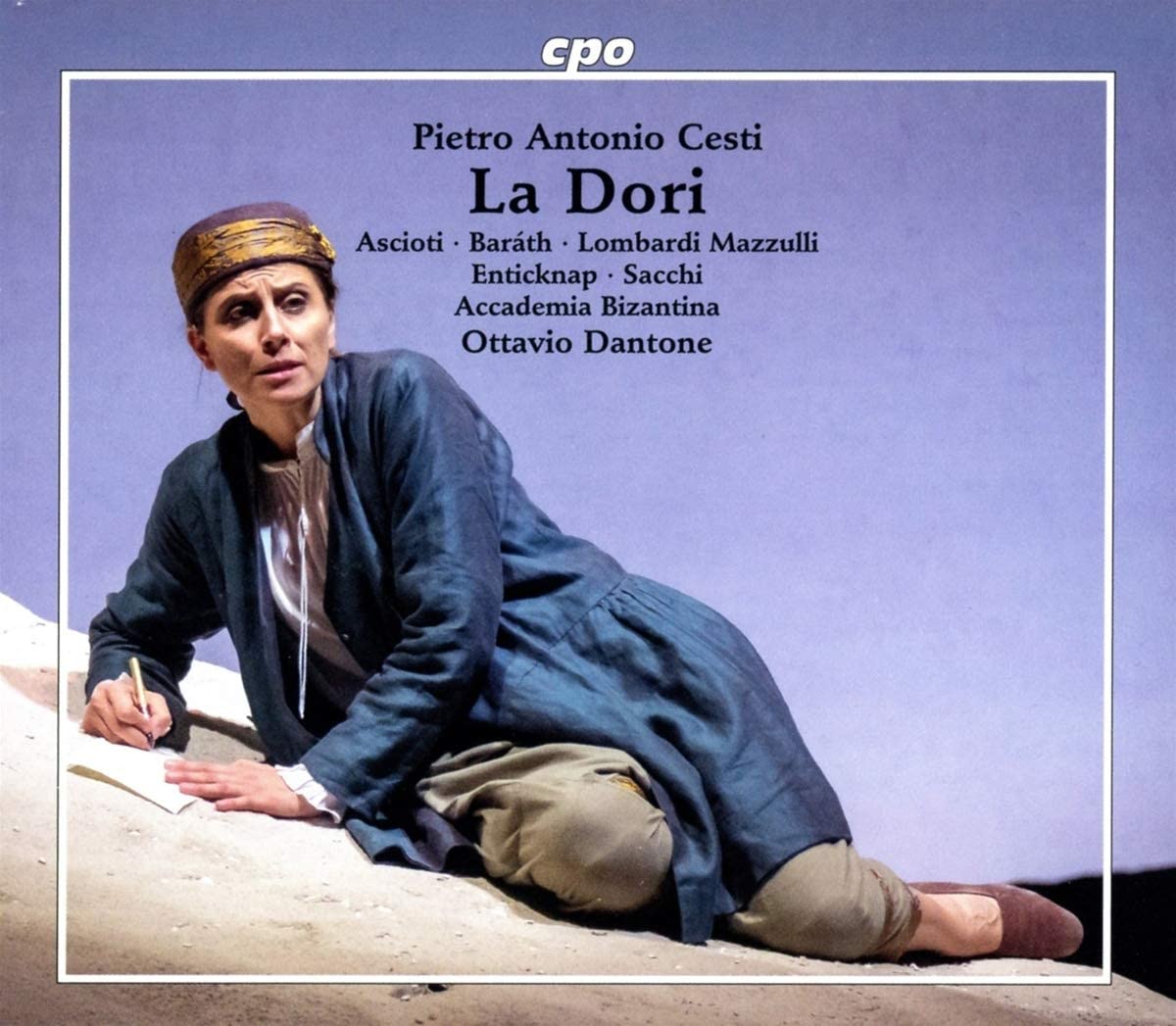

2019 marked the 350th anniversary of the death of Cesti, so for the Innsbruck Early Music Festival to, as it were, bring La Dori home for that year’s edition was a particularly felicitous idea, the results of which are now available on this set. I was fortunate enough to be there, happily one of the most exhilarating productions of a 17th opera I’ve yet to see, sympathetically staged, with outstanding lighting, and sumptuously and colourfully costumed, in keeping with its being set in Babylon. Quite apart from much outstanding music, La Dori has the advantage of a splendidly varied libretto of high literary standard by Giovanni Filippo Apolloni. The story is highly complex, involving an arranged dynastic marriage that is very nearly foiled multiple times both in the prehistory of the plot and during the course of the opera itself. At breath-taking pace we are taken through a series of events involving mistaken identity, disguise, love intrigues and comic interludes, the latter mostly involving that stock character of Venetian opera, the old nurse Dirce, a role sung here with comic relish by tenor Alberto Allegrezza. Cesti’s music runs a wide gamut between tuneful dance-like arias in triple time to ravishingly sensual love music and near-tragic solo scenas, sometimes in close juxtaposition. At the pivotal point in act 2 Prince Oronte, still seeking his Dori, but having been convinced she is dead, dictates to the slave Ali (Dori in disguise) a letter to Arsinoe, the woman it has been arranged he will marry in the stead of Dori. It is a poignant scene, handled by Cesti with sensitivity and consummate dramatic skill and beautifully sung and vocally acted by Rupert Enticknap (Oronte) and Francesca Ascioti (Dori/Ali).

In keeping with the minimal instrumental forces customarily required for Venetian opera, La Dori is scored for continuo with two violins, whose role is near-exclusively confined to ritornellos. Ottavio Dantone has opted for a rather more generous orchestration, with three first and three second violins at times joined by recorders and a rich continuo group that includes the anachronistic addition of harp and chamber organ in addition to the expected bass strings, theorbos and harpsichords. Notwithstanding the continuo is deployed with such sensitivity and musicality that anything but the mildest censure is stilled, particularly in the face of direction that captures the essence of the work with unerring empathy and a thrilling sense of theatre. Dantone’s insistence on his singers devoting unusual attention to words is especially apposite in text-driven operas like La Dori and bears fruit in the vivid declamation in recitative and beautiful expressed Italian in cantabile music. His entire cast in fact does him credit. Emőke Baráth’s Tolomeo/Celinda (a woman playing a man disguised as a woman – I did warn you!) is sung with complete tonal security, while soprano Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli is a touching and impressive Arsinoe. The smaller roles are all exceptionally well taken. My only caveat is that I would have liked to have heard more ornamentation and for what is heard to have been more stylish and clearly articulated. That said this is one of the most musically and dramatically satisfying recordings of a Venetian opera available. La Dori deserves to be far more widely known; its pace, colour and variety would make it an ideal opera for Glyndebourne.

Brian Robins