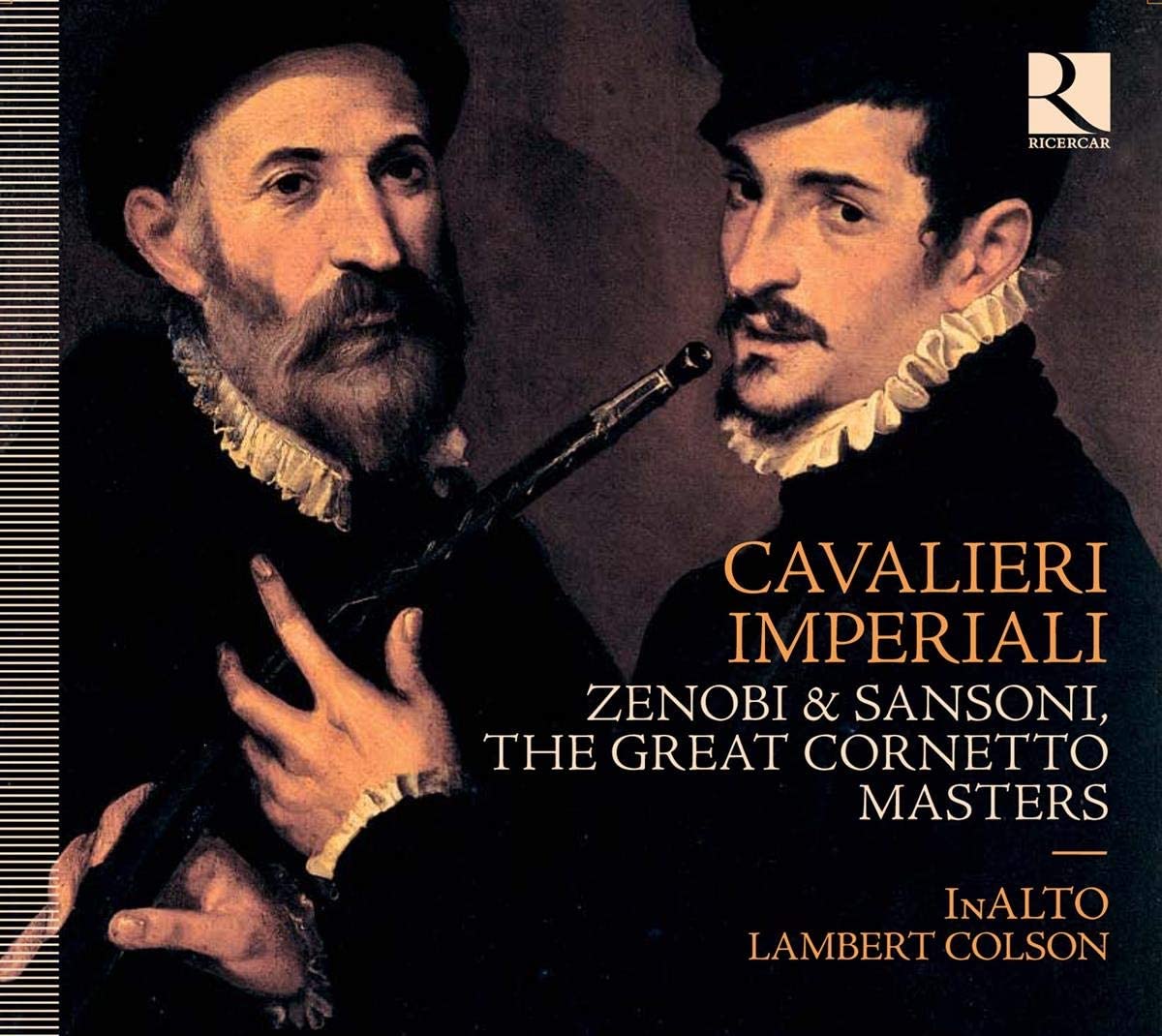

Ensemble Clément Janequin, Dominique Visse

61:14

Ricercar RIC423

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

Most of the works on this recording are selected from Le septiesme livre, which consists of 24 chansons, mainly by Josquin, in five and six parts, which was published in Antwerp by Tielman Susato in 1545. Fifteen of Josquin’s compositions appear on the disc, all but one from this livre, plus two laments for him by Gombert and Vinders, both of which are included in the livre, also two solo instrumental settings by Narvaez and Newsidler of the chanson Mille regretz which is usually attributed to Josquin, though the earliest, and unique, attribution to him is in a late source, Susato’s L’unziesme livre of 1549. In most other early sources it is anonymous, although in one it is attributed to Lemaire, who is thought by some musicologists perhaps to be the author of the text; Josquin is known to have set another poem by him. Of more significance in the context of the present recording is that the rest of the chansons have so far survived the recent scholarly attempts to give his oeuvre a short back and sides. Any selection of pieces by Josquin is going to consist of distinguished music, so the success of a programme such as this lies in the process of that selection, and its presentation. Although any sequence of such works can of course nowadays be shuffled, the order in which the items appear provides a variety of content, both in subject matter and in scoring. For this listener the most striking work both as music and interpretation is Baises moy ma doulce’ amye. Originally in four already canonic parts, it appears posthumously in this livre in six parts, with an extra canon. Its text of seeming triviality is set incongruously to music with a dense texture rendered the more intense by dramatic dissonances; one could almost be listening to a work by Gombert, with Tallis distantly audible, and Byrd’s unpublished O salutaris hostia on the musical horizon.

It is a pleasure to listen to this repertory, but not in these performances. The faux-rustic tonal quality becomes wearing, and the bucolic conclusion to Allegez moy douce plaisant brunette is irritating on repeated hearings. Given the nature of many of the texts, it certainly would not be appropriate to sing these chansons in the manner of canticles at choral evensong, but the uningratiating timbre that the singers adopt tends to grate. (Cut Circle carry off this manner of singing on their recent disc of Ockeghem’s songs, Musique en Wallonie MEW1995, my review posted October 15.) Most performances are accompanied by one or two instruments: lute and/or positive organ or muselaar. These add nothing to the performances, and it is ironic that the author of the excellent booklet justifies the inclusion of instruments on the basis of wording on the title-pages of the Sixiesme and Huitiesme livres in Susato’s series from 1545, while there is no mention of instrumental participation in the Septiesme livre from which most of these pieces are taken. An exception is La Bernardina played here on the lute and organ, which is not from this livre and survives as a textless composition. Cucur langoureulx, another wonderful work with pre-echoes of Gombert, is sung without accompaniment but this exposes some unattractive vowel sounds, while the rendering of Ma bouche rit, coming as it does after the effective Baises moy ma doulce’ amye, contains some sour tuning during the initial forced heartiness, though the more sedate ending is well handled. It is good that the two laments for Josquin by Gombert and Vinders are included on this disc, even if these performances would not be first recommendations for either work, especially the latter with more sour tuning on the top line, a fault also audible in Plus nuls regretz. The presence of Gombert’s classic illustrates just how much he learned from Josquin. For this reason and for those given above, the material on this disc has been well chosen. Other listeners may well be less troubled by the performances.

Richard Turbet