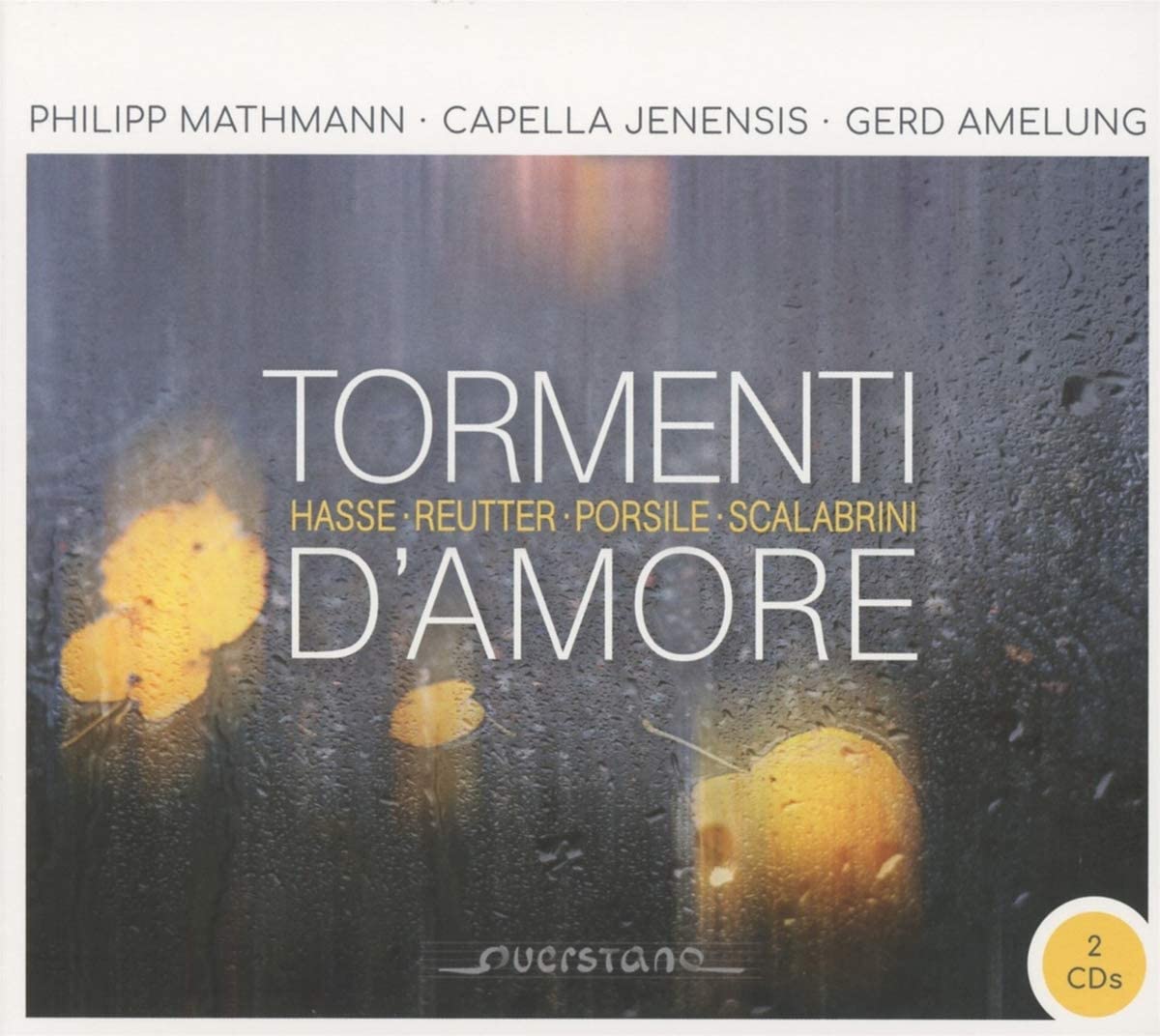

Philipp Mathmann, Capella Jenensis, Gerd Amelung

82:13 (2 CDs in a card triptych)

Querstand VKJK 2002

Music by Hasse, Porsile, Reutter the Younger & Scalabrini

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

This set is centred around a collection of vocal music made by Prince Anton Ulrich of Saxe-Meinigen during the period he spent in Vienna, where he apparently arrived in 1724. Apparently, since the notes rather ambiguously tell us that the collection, consisting of nearly 300 vocal works, including over 170 chamber cantatas, were works from ‘Vienna’s musical scene composed between 1710 and 1740’. So the assumption would be that Anton Ulrich spent around 20 years of his life in Vienna. More importantly, many of the works in the Meinigen Archive are the sole surviving copy, including the best music in the programme, the two characteristically melodious and elegantly turned cantatas by Hasse. The cantata by Georg Reutter, the Court Composer of Vienna and Kapellmeister of St Stephen’s Cathedral who brought Haydn to Vienna, and the Neapolitan opera composer Giuseppe Porsile are less interesting, the former in particular also suffering from an excruciating anonymous text on the prevailing topic of the cantatas – tormenti d’amore, the torments of love.

In addition to the cantatas, the set includes two trio sonatas by Hasse and two sinfonias once surprisingly attributed to Hasse, but more recently established as the work of the Italian-born Paolo Scalabrini (1713-1803 or 6), the director of the travelling Mingotti opera company, who ended up as maestro di cappella in Copenhagen, where he composed at least eight operas, including several Danish-language works that helped establish native opera. They are pleasant enough routine Galant works in three brief movements but little more and assuredly not worthy of Hasse’s name being attached to them.

The programme itself is therefore not without interest, but sadly the performances rarely rise beyond the level of the efficient and in the case of the cantatas fail to reach that level. Philipp Mathmann, confusingly described as a countertenor/soprano, is in fact a sopranist pure and simple. While the voice has an admirable purity and wide range, it is unfailingly hooty in its upper range, while also displaying deficient technique in several respects. Little ability to articulate a simple turn is shown, while more complex embellishment or ornamentation is rarely attempted. What truly compromises Mathmann’s performances, however, is his seeming lack of interest in the texts he is singing. None is a literary revelation but the whole object of the chamber cantata was to move the listener, evoking sentiment and emotion through expressive vocal gesture and realization of the words. Ignore that and you may as well be singing a vocalise, which is precisely the impression given here for much of the time.

The instrumental contribution of Capella Jenensis is rather more enjoyable, though rhythms tend to plod in slower movements. The Hasse trio sonatas, in particular, are well played, with pleasing shaping of melodic lines from the two violinists and – in that in D, op. 2/2 – flautist. The programme, almost exactly the length possible today on a single CD, is extravagantly spread over two discs so it is to be hoped that some price concession is built in.

Brian Robins