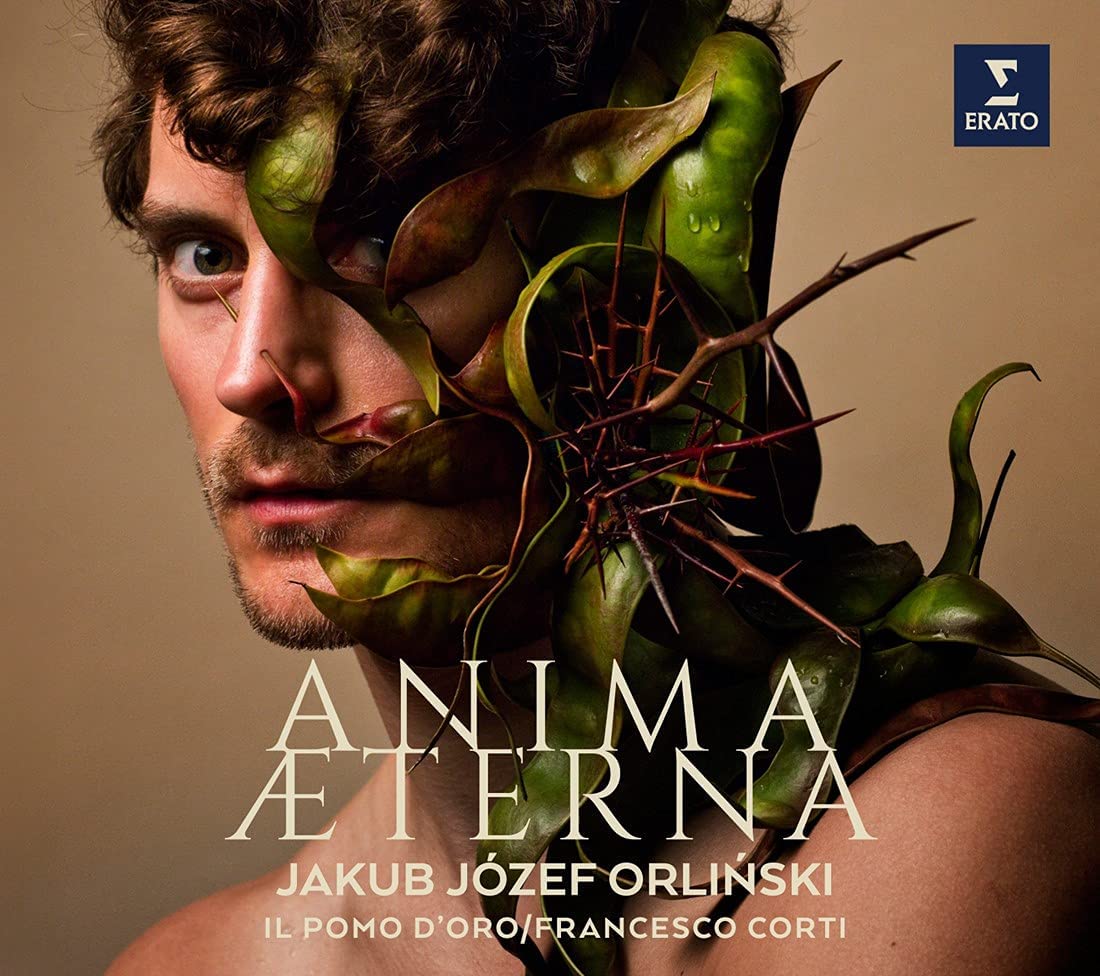

Michael Spyres Mitridate, Julie Fuchs Aspasia, Sabine Devieihle Ismene, Elsa Dreisig Sifare, Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian Franace, Cyrille Dubois Marzio, Adriana Bignani Lesca Arbate, Les Musiciens du Louvre, Marc Minkowski

151:11 (3 CDs in a card box)

Erato 1 90296 61757 7

Click HERE to buy this album on amazon

[Doing so supports the artists, the record company and keeps this site available – if no-one buys, no money is made and the site will disappear…]

Mitridate represents an important milestone in Mozart’s composing career, his first attempt at composing a full-length serious opera. It owes its existence to a commission received when father Leopold and the 14 year-old Wolfgang stayed in Milan in the early months of 1770 during the course of their first Italian tour. The subject of the libretto the boy was asked to set was a historical figure, King Mithridates , the despotic ruler of Pontus, a Hellenic country on the Black Sea today part of Turkey. Mithridates was a fierce opponent of the Romans, but – like most plots based on history – considerable licence was taken by the libretto of V A Cigna-Santi, who based his book on a play by Racine. It concerns the return of Mitridate to Pontus following defeat by Pompey. Suspicious of the loyalty of his own sons, Farnace and Sifare, not least their intention towards his young bride-to-be Aspasia, Mitridate inspires a rumour he is dead to test them. Sifare has indeed fallen in love with Aspasia, in so doing rejecting the gentle princess Ismene. Farnace on the other hand is revealed as the traitor who has fallen under the spell of Roman influence in the person of the Roman tribune Marzio. The opening is thus nicely poised for a conflict of loyalties and emotional turmoil of the kind on which opera seria thrived, indeed depended.

The opera was first given by a star-studded cast at the Teatro Regio Ducale in Milan on 26 December 1770, being well received and achieving a run of 22 performances, no mean achievement for a new opera in a major house at the time. Both the lavish staging and Mozart’s music were praised, the latter by the Gazzetta di Milano for his studies of ‘the beauties of [human] nature and representing them ‘adorned with the rarest music graces’. The opera is in the usual three acts, dominated by the customary da capo arias and just a single duet (between Aspasia and Sifare) to end act 2. Less conventional is the number of accompanied recitatives (6) that perhaps better than the arias show the young composer’s astonishing and seemingly innate ability to lay open human emotions, often of a profundity and complexity he should not have been able to understand at such a tender age.

As befits a glamorous cast, many of the aria are virtuoso pieces that, as was customary in the 18th century, were tailor-made by Mozart for the singers, with whom he worked closely to ‘fit the costume to the figure’, as he figuratively put it. Such demands frequently give problems to casting such operas today in particular tenor roles such as Mitridate. In this new Minkowski recording Michael Spyres, justly much admired for his singing of later music, in particular the heroes of Berlioz, proves to be no exception. While he is admirably authoritative and at times sensitive, the tessitura in an aria such as the heroic ‘Vado incontro’ (act 3) tests him to the limit, as can be readily heard in some of the less than pleasant sounds he makes above the stave. There is also too much continuous vibrato in the voice and some of his cadences are vulgarly ornamented. Since the latter (and one might almost say the same of the former) is a common problem throughout the set, one can only assume they were what Marc Minkowski wanted. Otherwise there are some satisfying performances, in particular those of Julie Fuch’s Aspasia and Elsa Dreisig’s Sifare, who are particularly sensitive in the lovers’ exchanges in act 2. Sabine Devieilhe brings a lovely, tender quality to the role of Ismene, a prototype for Ilia in Idomeneo. The generally stylish countertenor Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian is an excellent Farnace, his performance reaching a fitting climax and attaining true nobility in act 3’s ‘Già dagli occhi’, a fine extended aria in which he renounces and repents his treachery.

Minkowski’s direction is uneven, as so often with conductors today playing allegros too fast and slower tempos too slowly. This is particularly marked in act 1, with its preponderance of quick arias, almost without exception driven by the conductor in a manner that not infrequently sounds aggressive. Thereafter the approach allows for rather more nuance and sensitivity, and there is much to enjoy. Howeve, overall I think this performance too uneven to compete with the fine and certainly more idiomatic performance directed by Ian Page (Signum). Moreover Page’s version is obligatory for all serious Mozartians for its inclusion of a fourth CD devoted to variants of a number of the arias that show how much work Mozart put into satisfying both himself and his cast.

Brian Robins