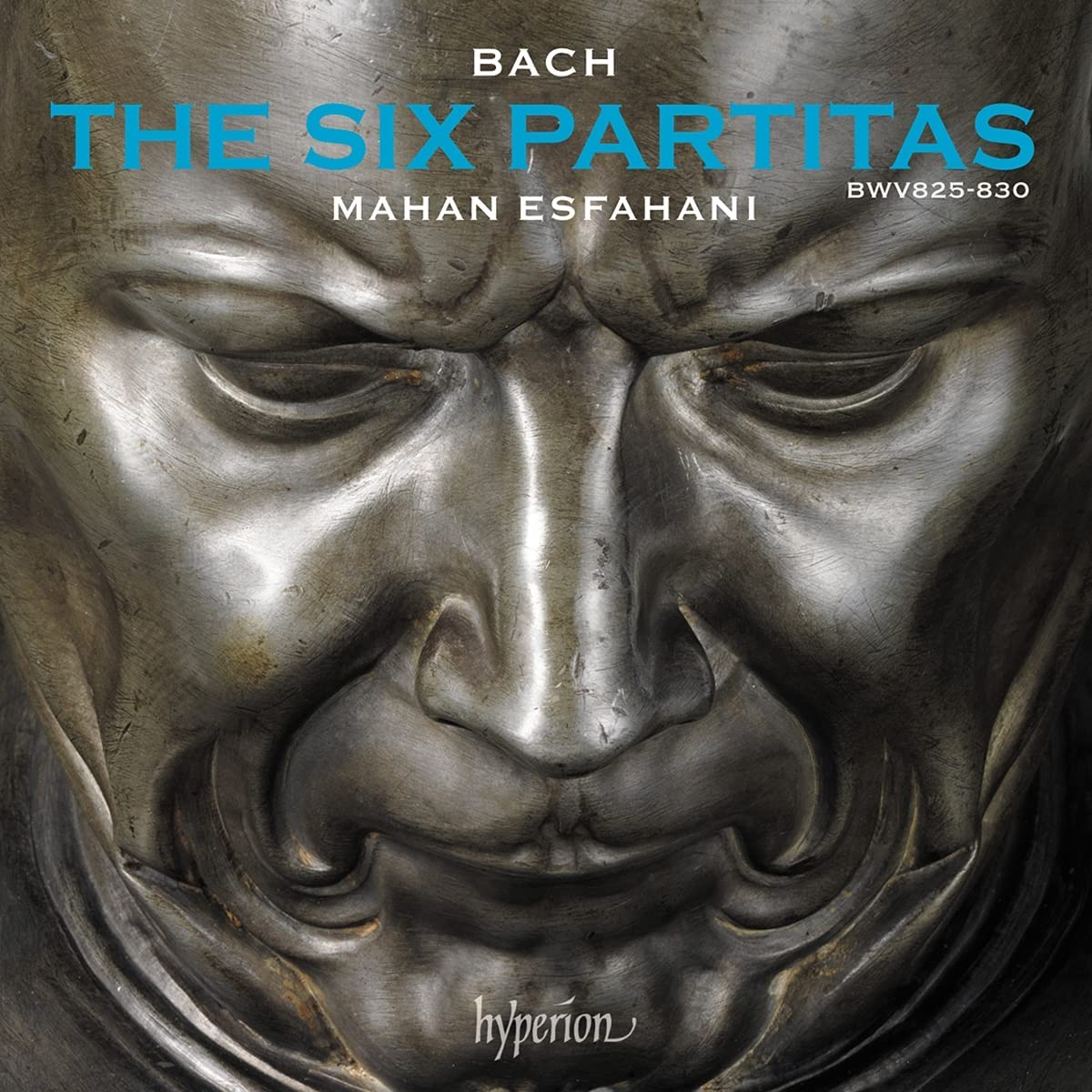

Mahan Esfahani harpsichord

148:43

hyperion CDA68311/2

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[These sponsored links help the site remain alive and FREE!]

Mahan Esfahani is very much a crusader for solo harpsichord music and you do not find him playing chamber music with period instrument players for example, as many of the keyboard players who record these works do. His approach is more individual and rhapsodic as a result, and he has managed to make solo harpsichord music a Box Office success in a way that more conventional ‘Early Music’ specialists haven’t. In this, he has been patronised by John Gilhooly who has been producing remarkable concerts from the Wigmore Hall during the lockdowns of the past year, and to whom Esfahani pays tribute in his liner notes.

On this recording, as on his hyperion Bach Toccatas, Esfahani plays a 2018 instrument from the Prague workshop of the Finnish maker, Jukka Ollikka, ‘based on the theories and surviving examples of Michael Mieke with the hypothetical addition of an extra soundboard for the 16’ register and a cheek inspired by Pleyel 1912; the disposition is as follows: 16’8’8”4’ with buff on the upper manual/soundboard from carbon fibre composite, EE to f3/length 2.8 metres.’ The temperament is set by Simon Neal and is ‘based on various 18th-century German temperaments, a’ = 415Hz.’

As we know from his liner notes and playing, Esfahani is a passionate performer rather than a scholarly purist and chooses the readings, like his choice of instrument, that make most musical sense to him – the sources he has consulted are all listed. There is a good note listing the scholars with whom he has discussed the readings and a tribute to the audiences in Bratislava, whom he credits with ‘the keenest and most focussed ears of any classical music listeners I have ever encountered.’ On the rare occasions when he cannot decide, as in the mysterious notation for the Gigue at the end of the E minor Partita, he plays the movement on different repeats in both triple and duple metres.

The instrument delivers a smooth and homogenous performance under Esfahani’s nimble fingers, and – as always – his readings, as well as his playing, challenges many of the more conventional ‘period instrument’ assumptions. Among those is the quite excellently played and well-argued performance by Richard Egar for Harmonia Mundi, which is more my style I have to confess.

But I recommend this recording not just for its well-argued and committed performances but for Esfahani’s challenging approach. He is on the way to recording all Bach’s keyboard for hyperion, and if you like his style they will be well worth watching out for.

David Stancliffe