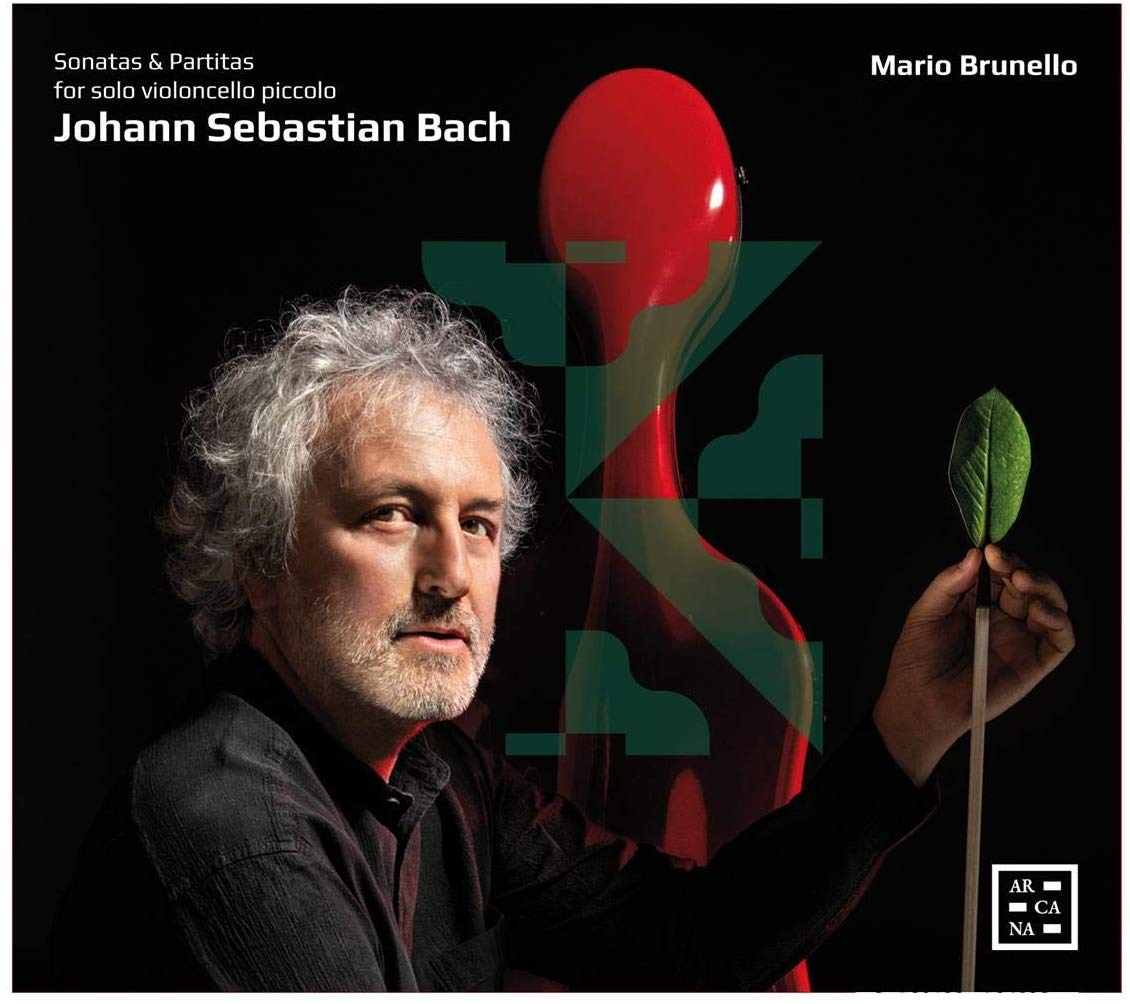

Mario Brunello

161:00 (2 CDs in a card folder)

Arcana A469

First we had Rachel Podger playing the ‘cello suites on the violin, and now we have the cellist Mario Brunello playing the Sei Soli – the sonatas and partitas for solo violin (BWV 1001-6) – not on a violin, but on a four-string violoncello piccolo made Filippo Fasser in Brescia in 2017. The model is an instrument by Antonio and Girolamo Amati of Cremona dated between 1600 and 1610; the pitch is A=415 and the bows and strings are all detailed in the booklet which contains a mood piece entitled ‘An unexpected gust of wind’, an essay dated 2019 by Peter Wollny ‘Johann Sebastian Bach and the violoncello piccolo’, and finally Brunello’s article on playing the Sei Soli on the violoncello piccolo ‘A looking-glass reading’ during which he observes that while a violinist naturally strokes the highest string first, with a cellist it is the other way round: the texture builds up from the bass line.

In the fugal writing in particular, this gives a different perspective to the polyphony that Bach creates from the single instrument, and listening to these performances of the Sei Solo is a richly rewarding experience, offering a new take on Bach’s artistry, and in particular on the way in which a single instrument can, and in this case does, create a complete fugal texture. I was expecting some of the lighter dance movements in the Partitas to feel heavier and lumpier, but this is not the case. The bottom-up bowing seems to lighten the texture, and let the strong/weak pairing of notes find a natural sense of being placed just right. In addition, the baritone register of these pieces, likened by Brunello to a counter tenor’s take on music we are used to hearing in a different register, seems less anguished and tormented than many versions we are used to hearing.

The instrument sounds responsive: its light, singing tone fills the space in which the recordings were made – the Villa Parco Bolasco in Castelfranco in the Veneto – and is far removed from the grainy, hard-worked sound of Peter Wispelwey’s ‘cello in his later recording of the Six Suites, for example. A 4-string violoncello piccolo (without the bottom string of a 5-string one) is pitched exactly an octave below a violin, so although the register sounds strange at first, by the time we are into the D minor partita, the great ciacconna sounds as if it was always meant to be pitched there, and because, I suspect, of the slacker bow, the chords of the D minor chaconne (in BWV 1004) and the great fugue in the C major (BWV 1005) to take two obviously ‘polyphonic’ numbers sound as convincing as I have ever heard on a violin.

So like Rachel Podger’s ‘cello suites, I love these versions. The novel tessitura offers both challenges and insights, and I ended up after several listenings thinking that this was a more comfortable pitch for the music. And Bach did re-pitch his favourite material. He made several different versions of, for example, the resoundingly bass/baritone tessitura of cantata BWV 82 Ich habe genug, transposing it up both for soprano and for alto and altering the instrumentation with each reworking, notwithstanding the obvious identification of the bass singer with old Simeon in the Temple. In the same way I hope that this version of the Sei Soli will find a ready following among those who can get hold of such an instrument, and appeal to listeners as a proper reworking of well-known music that offers new but valid insights.

Singers as well as string players would do well to listen to this recording and to ponder what this might mean for the way they sing their Bach. And I urge violinists as well as ‘cello players to listen and learn from this enormously rewarding performance; I have learnt a lot.

David Stancliffe

Click HERE to buy this CD on amazon.co.uk

2 replies on “Bach: Sonatas & Partitas for solo violoncello piccolo”

And unlike Podger, he presumably needed no help from technological trickery to realize his intention. Sounds intriguing.

No: just straight playing.

I’d like more details on the instrument though,