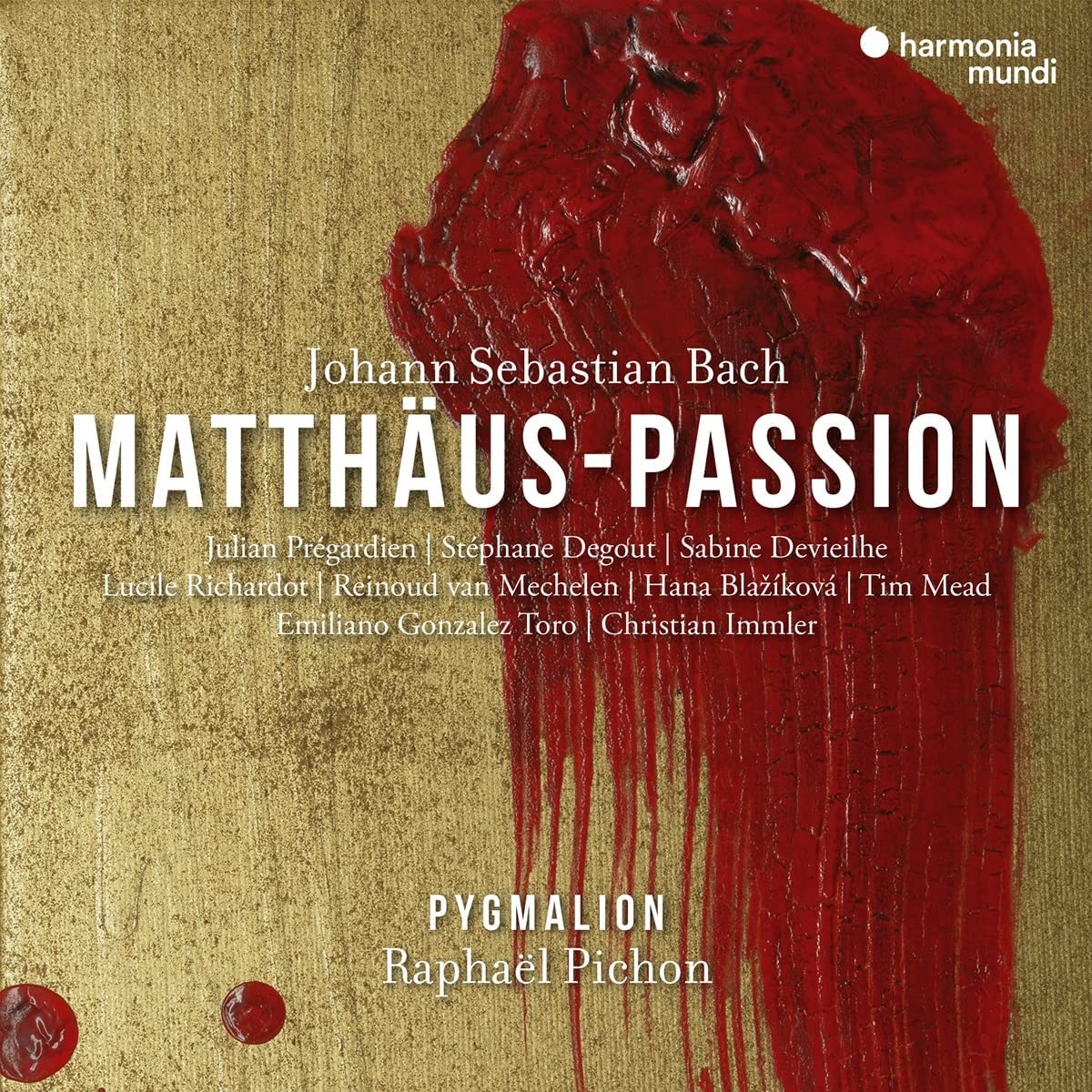

Julian Prégardien, Stéphane Degout, Sabine Deveilhe, Lucile Richardot, Reinoud van Mechelen, Hana Blaz>iková, Tim Mead, Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, Christian Immler, [Maîtrise de Radio France], Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon

162:00 (3 CDs in a card box)

harmonia mundi HMM 902691.93

Click HERE to buy this on amazon.co.uk

[Sponsored links like this provide a VERY small income for the people who maintain the site]

This splendid recording of the St Matthew Passion by Raphaël Pichon’s Pygmalion has been a long time in gestation. It is worth the wait. First, it is technically excellent: clean, well-balanced and every line can be heard without distortion. Second, the dramatic structure of the work – so different from the St John – is carefully thought through and well-presented in a series of scenes between two book-ends: the Preparation of the Passover, the Garden, at the High Priests’, before Pilate, the Cross and the Burial. But most importantly, this is the first recording of the St Matthew that I have encountered where real care has been taken to match the quality of the singing voices to the resonance and sound quality of the period-instrument bands, and the result is arresting.

The forces are quite large. Each line in the two choirs is led by the concertisten singer who sings the arias allocated by Bach to each choir, and each choir has five soprano, two alto, two tenor and four bass ripienisti singers in addition, so the choral sound – though fairly substantial – matches the ‘solo’ singing. The only singer excluded from the choro is the Evangelista, Julian Prégardien, whose place leading the tenors of choir 1 is taken by the admirable Reinoud van Mechelen, whose high voice has that distinctively clean yet mellifluous ring. It is he and the alto of choir 1, Lucile Richardot, who exemplify the vocal style that Pichon is after. When I first heard Buß und Reu, I was convinced that the pure, slightly nasal, ringing tone was a male voice. Richardot matches the flutes so well, but is equally flexible and commanding with the strings in Erbame dich: these two are exactly the type of voices that work for me.

Sadly, the standard set by Richardot and van Mechelen is not met by the soprano or the bass of choir one. For all her admirable phrasing in Ich will die mein Herze schenken, Sabine Devieilhe is unable – or unwilling? – to control the wobble in her voice. Singing in duet with Richardot in So ist mein Jesus nun gefangen – taken at a spanking pace with elegant ornaments and cracking interjections from the 2nd choir – she manages better, so it is a real pity that she falls back on modern, singerly sounds as her default option. The other weak link is the B1, Stéphane Degout, singing Jesus and those choir 1 arias. His voice, though rich and characterful, sounds plummy and bottled – a throwback to the singing style of an earlier period and out of kilter with the razor-sharp strings (3.3.2.1.1 in each band) who provide the halo round Jesus’ music.

The concertisten in choir 2 are well known soloists in Bach’s music. Hana Blažíková in Blute nur, Tim Mead in Können, Tränen and Christian Immler in Gerne will and Gebt mir produce quality performances that match the instrumental colour splendidly. The tenor Emiliano Gonzales-Toro was known to me chiefly as the singer/director of his own version of the Monteverdi Orfeo, but is equally admirable here in Geduld. All these singers make this recording outstanding for their ability to subsume their soloistic persona into the overall sound pattern Pichon is creating. The choruses have edge and bite, and many of them are refreshingly brisk. Chorales are treated to their own persona, and are an integral part of the whole drama rather than the boring but necessary hymns between the real music that they can so often become.

Julian Prégardien is a wonderful story-teller, at once tender and dramatic, and with a feeling for the shape and import of each phrase within the whole narrative: his diction – a significant feature of every singer in this recording – is outstanding. It is this sense of drama that pervades this recording and provides its distinctive and very French take on the Great Passion. Apart from the full libretto, translated into both French and English, which occupies pages 38 to 105 of the substantial 111-page booklet in rather grey, arty typeface – so not easily readable –, there is room only for a basic list of players and singers together with one of those composite and very French interviews with Pichon and Prégardien about how they planned their take on the Matthew over a number of years. There is nothing about the music itself, its sources, versions, transmission and readings; nor about the singers, players, instruments or chosen temperament; nor about the key musical decisions such as when and where to use dual accompaniment, adding the harpsichord of choir 2. The basso continuo instruments are listed as a group together as in Bach’s very first version as well as with their respective orchestras – theorbo and organ with choir 1 and organ and harpsichord with choir 2. Why and where are the bassoons (present in both orchestras) added or do the violas da gamba play in more than the specific arias where they are scored? All of this suggests to me that Pichon is more interested in dramatic affekt than in serious HIP scholarship and I am left with a lot of unanswered questions. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but the buyer should beware.

Nonetheless, and despite my personal reservations about the suitability of two of the singers (which listeners may not share), this is an outstanding performance by any standards, and I warmly encourage everyone to buy it. It is on three CDs and is a real bargain, and the thought that has gone into its preparation and direction makes a welcome change from many of the more lumbering and dully correct performances to which we are often treated. I find the style, tempi and continuity convincing, while stripping away the varnish of respectability brings a glow of excitement to the treasure that lies beneath.

David Stancliffe