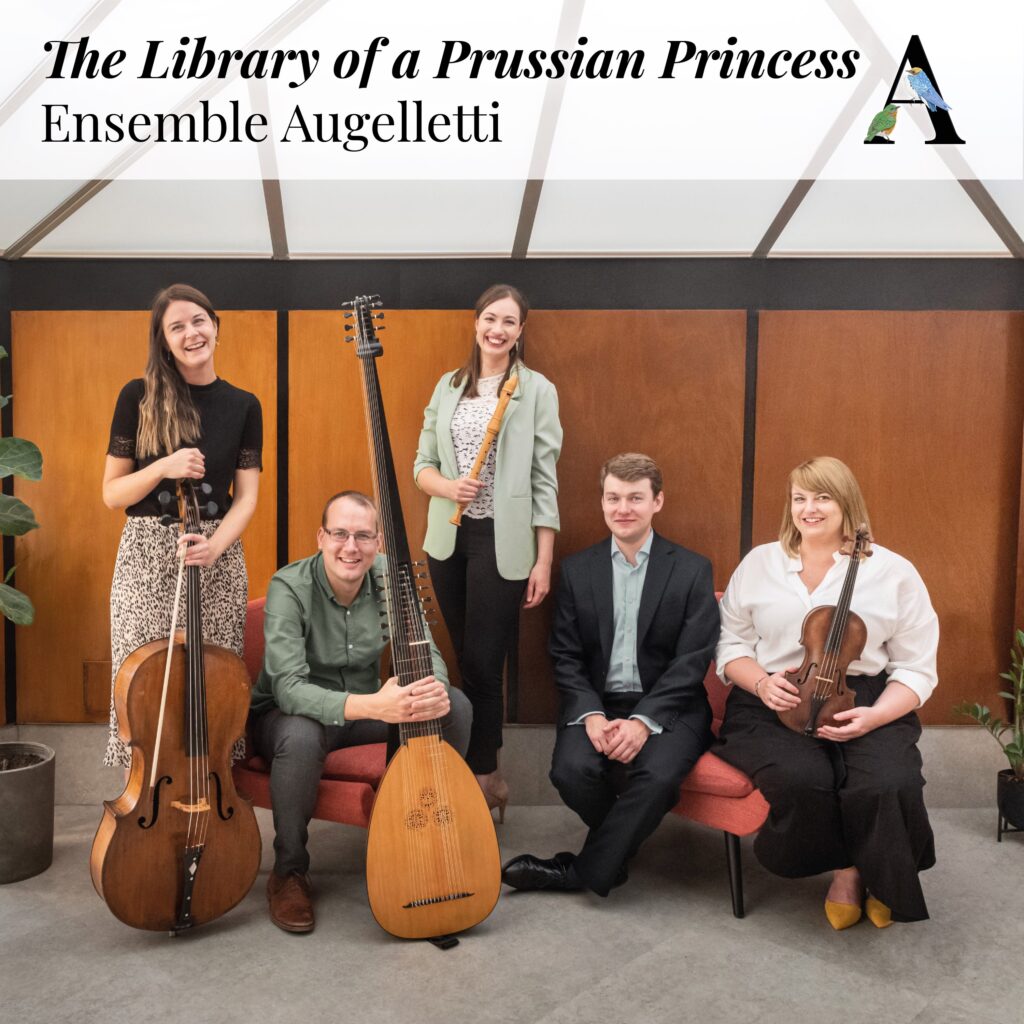

Ensemble Augelletti

60:25

Barn Cottage Records BCR024

For further information, visit https://barncottagerecords.co.uk/

Anna Amalia, Princess of Prussia (and titular Abbess of Quedlingburg) is one of the great collectors of music to whom musicians owe a great debt. In compiling this intriguing programme, Ensemble Augelletti have searched through her remarkable library of more than 600 pieces, using it as a source for even the well-known pieces recorded here. These are placed side-by-side with less familiar repertoire, including music by Princess Anna Amalia herself, in the manner of a soirée in her palace on Berlin’s magnificent avenue, Unter den Linden. Reflecting the Princess’s devotion to the organ – she had one built specially for her in 1755, described herself proudly as ‘organist’, and had it moved with her to Unter den Linden – the continuo here is played on organ and viol with theorbo. The melody instruments are recorder and violin, although there is a disappointing lack of information in the notes as to precisely who does what and on what. As I mentioned, this imaginative programme plan allows for the very familiar to rub shoulders with the thoroughly unfamiliar – in the former category we have two trio sonatas by J. S. Bach, and one each by C. P. E. Bach, Handel, Corelli and Geminiani and in the latter, four fugues for trio by Princess Amalia. While not perhaps being of a standard with the other works, Amalia’s fugues are thoroughly workmanlike and full of original turns of phrase. The playing from the Augelletti Ensemble throughout this CD is delightful and sympathetic, and they bring the same infectious enthusiasm to their performances as Princess Amalia seems to have brought to her Unter den Linden soirées – important events in their own right, and doubly so for having influenced those hosted subsequently by Sarah Levy, the great-aunt of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn.

D. James Ross