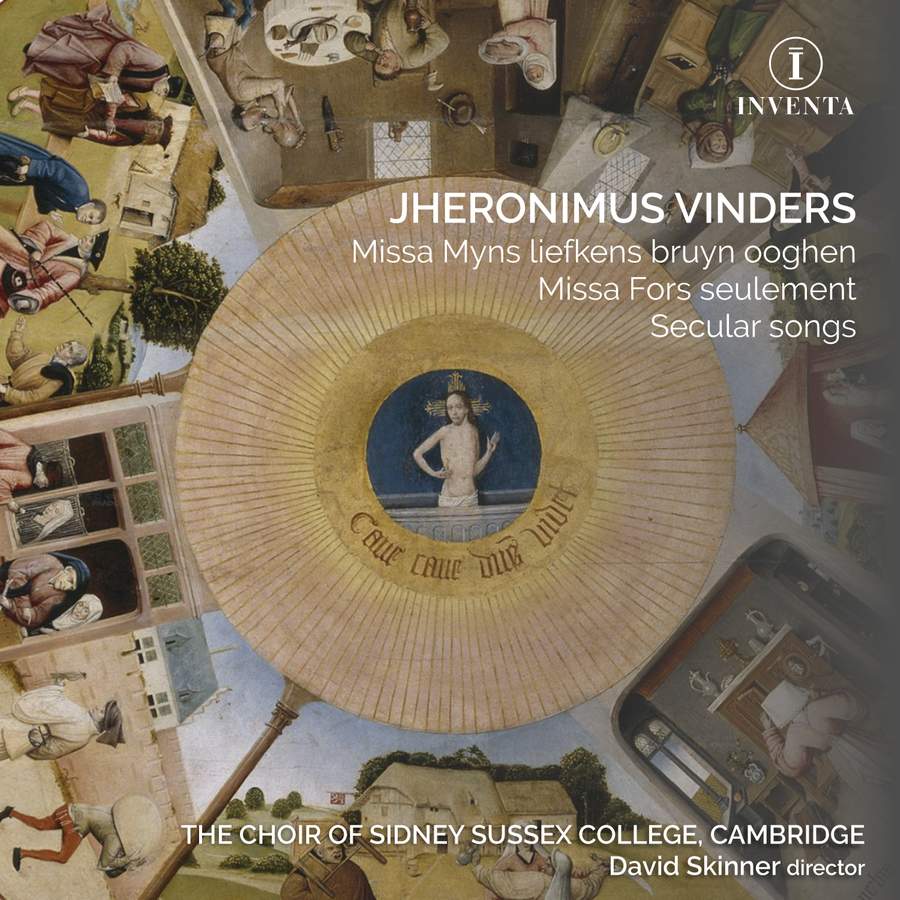

Missa Myns liefkens bruyn ooghen; Missa Fors seulement; Salve regina; secular songs

Choir of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, conducted by David Skinner; Andrew Lawrence-King, psaltery and harp

101:17 (2 CDs in a single jewel case)

Inventa INV1012

Jheronimus Vinders: another fine Franco-Flemish composer who has been waiting in the wings for discovery, and now, thanks to Eric Jas who has edited his complete surviving works, and David Skinner and the Choir of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, who have recorded these three wonderful works, Vinders can begin to receive the recognition that is his due. All that is known about him biographically is that he was in Ghent during 1525-26. Stylistically his music sits between Josquin, for whom he composed the lament O more inevitabilis which is the only work by which he is currently known, and Jacob Clement. Qualitatively it is on a par with the best composers of that era.

This recording consists of two masses based on folksongs, plus illustrative settings of those songs, performed vocally and instrumentally, including the versions on which Vinders based his masses. These musical strands are all unpicked fascinatingly and lucidly by Eric Jas in the accompanying booklet. In particular, he explains the process by which it has been possible to affirm the attribution to Vinders of the Missa Myns liefkens bruyn ooghen despite its being anonymous in its source. The other mass is also attributed to Gombert but, despite some echoes of that master in its music – such as the almost obsessively thrummed repetitions – it is also most likely that a chronologically earlier ascription to Vinders is correct.

The music of both masses is intense, in minor mode, and tightly rather than thickly scored. Vinders sustains interest throughout all the movements with varied textures, striking melodies and vivid harmonies. Particularly notable are the beautiful sonority at “Tu solus Dominus” in the Gloria of Missa Myns liefkens and a breathtaking cadence on “Sabaoth” in the Sanctus, which is beautifully executed by the singers. In the Missa Fors seulement there is a sweeping opening to the Kyrie, the music of which is taken over wholesale for the Agnus. The album also contains an absolute peach of a Salve regina a5, one of three surviving settings by Vinders.

The singing by the Sidney Sussex choir in a reverberant acoustic is excellent, with attention to detail and clarity of individual parts. David Skinner’s tempi are judicious, and of considerable interest is his decision to take the Gloria slowly from “Qui tollis” almost right to the end of the movement. The instrumental pieces are played by Andrew Lawrence-King on the harp and the psaltery, an inspired choice for music of this period which suits the relevant pieces admirably. Vinders’ music is a wonderful discovery, and the greatest compliment one can pay this recording is to express a wish to hear much more of it.

Richard Turbet