Published by Taverner

504 pp

ISBN 978-1-915229-53-3 Hardback – £65

ISBN 978-1-915229-54-0 Paperback – £35

ISBN 978-1-915229-86-1 ebook – No detail of availability

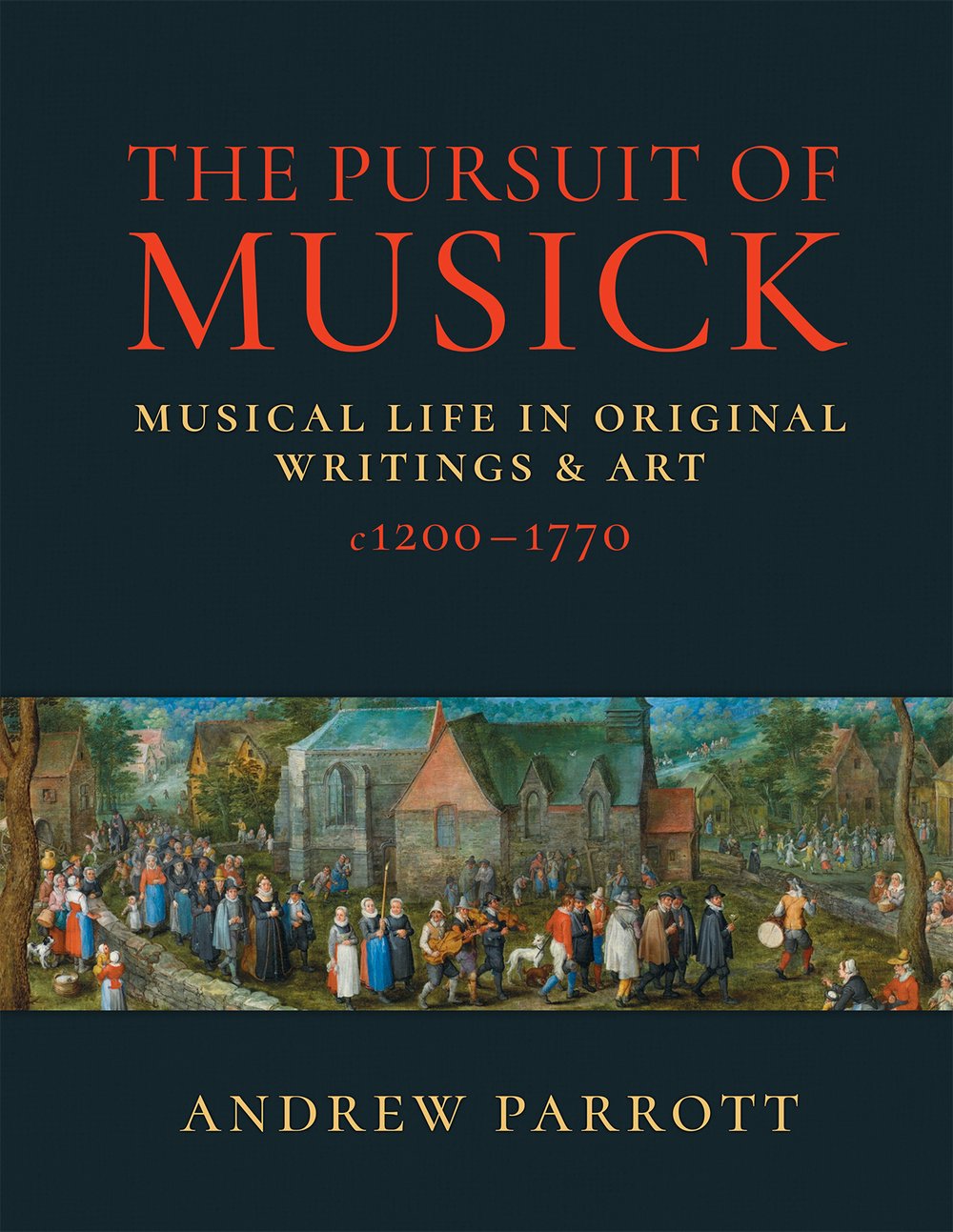

I can find no better way of introducing this review than by quoting the opening sentence of the online blurb: ‘The Pursuit of Musick is an encyclopedic and generously illustrated anthology of original written sources, exploring some 600 years of musical activity in Europe, from the first troubadours to the emergence of the pianoforte’. For once lacking hyperbole, this is a succinct and factual description of what is a remarkable and beautifully produced book. Printed on heavy gloss paper -the paperback I have to hand weighs in at 2.3kg – that enables the lavish and profuse artwork to be reproduced to the highest quality, it will be concluded that this is no bedside table book!

Those that have kept in touch with Andrew Parrott’s activities, which sadly have involved little in the concert hall or opera house more recently, will know that he has been thinking about this book for some years. Parrott’s eventual objective, which he only arrived at after several transitional ideas, was to allow the musicians (and the artists that involved themselves in their works) to speak for themselves with only brief introductions heading sections. The Book is divided into three parts: ‘Music & Society’, Music & Ideas’ and ‘Music & Performance’, which themselves are sub-divided into numerous sub-headings. Part 1, for example, includes sections devoted to music in everyday life, the church, music at court and so forth. Not the least of the book’s attractions is its meticulous indexing of the source material, in the book itself for paintings, online at taverner.org for literary material.

There are two groups of people to whom this book is surely going to be an obligatory part of any music library: musicians involved with early music and writers and critics who also have any depth of involvement with the subject. Doubtless there are also many others that will take not only didactic interest but also an aesthetic one; it would be possible to pass many a rewarding and pleasurable hour just browsing the hundreds of illustrations. It will be obvious from the foregoing that this is indeed not a book for reading but one to use for research or simply the sheer enjoyment of dipping into it at random. I would imagine that on first acquaintance most readers will make for topics in which they have a particular interest. That was certainly my course in the limited amount of time I’ve had to so far examine the book. Thus my first ports of call included the sections on performance practice, vocal music and opera. In the case of the first named I was delighted to find solid support for one of the most frequent moans in my reviews – the over-fervent activities of theorbo players, particularly when they interfere with the vocal line. Here’s St Lambert in 1707: ‘the [continuo] accompaniment is made to support the voice, not to stifle or disfigure it with an unpleasant jangle…’ Or Bacilly in 1688: ‘If the theorbo is not played with restraint and there is too much complexity […] then it is theorbo accompanied by voice, not voice by theorbo’. It is fascinating too to find most of the ire directed at Italian players, for in my experience they are the worst culprits. But all theorbists should read, mark and learn.

When we turn to singing there are as many extracts concerning technique as might have been expected. One constant motif is the need for singers to maintain an ease of production, the sentiments behind these words of the German composer Hermann Finck (1527-1588) serving to illustrate universally acknowledged views that held good until the end of the period covered by the book: ‘Singing is not made more beautiful by bellowing and shouting: rather you should embrace all notes with spirit and understanding. The more a voice moves upwards, the quieter and sweeter the sound should be; the lower it goes the fuller it should be […]. Amen indeed to that. In an ideal world they are words that would be emblazoned on the portals of every singing conservatoire.

The section on Music Drama leads from the earliest sacred representations through court intermedi to opera itself. The extracts devoted to opera are notable for illustrating how much more writing there is on the topic by French writers than Italian, probably an accurate reflection, though it would have been possible to have struck more of a balance. These extracts are dominated by the unending war between proponents of Italian opera and those favouring the French rival, summed up in an anonymous publication in Florence in 1756 (possibly by Gluck’s reformist librettist Calzabigi) forecasting the desirability of the combination of the best elements of both: ‘The opera in Paris offers [the audience] only painted scenery, ballets, machines, a sparkling assembly & a deep hush. In Naples it presents them only with ravishing music, beauties that are unseen & an appalling hubbub. Everyone understands that out of these two kinds one good one could be made, but no one has as yet thought to suggest it’. Prescient words.

It would be easy to continue citing such jewels, but it is time to leave the interested reader to obtain the book. But before doing so it is perhaps worth noting that the illustrations themselves provide a fount of information; staying with opera one might cite the marvellous illustration on p. 223 by P D Oliviero showing the re-opening of the Teatro Regio in Turin in 1740. Here one notes the wonderful set with its colonnaded perspective (not dissimilar to what can be seen in Turin today), stage filled with far more figures (12) than we normally experience in Baroque opera production today and the disposition and number of the orchestral musicians. No fewer than 29 musicians are involved, seated in two rows with harpsichords and continuo at either end of the pit. Two people are serving refreshments, while several in the front row are turning round to look at the audience rather than pay attention to what is happening on stage, a clear reminder that 18th-century audiences rarely paid undivided attention to the performance.

This magnificent publication can be obtained only online from: https://www.taverner.org/store. At the time of writing (mid-December 2022) it was available in both formats at a reduced price.

Brian Robins